This week’s top three summaries: R v Owston, 2023 SKCA 101: s.271 #capacity for consent, R v Hess and Profetto, 2023 ONSC 3065: s.8 staleness and stereotypes, and R v AL, 2023 ABKB 505: SOIRA exemption.

Our firm focuses on representation in complex criminal trials and criminal appeals. We also provide ghostwriting services to other firms for written submissions. Consider us for your appeal referrals or when you need written submissions on a file.

Our lawyers have been litigating criminal trials and appeals for over 16 years in courtrooms throughout Canada. We can be of assistance to your practice. Whether you are looking for an appeal referral or some help with a complex written argument, our firm may be able to help. Our firm provides the following services available to other lawyers for referrals or contract work:

- Criminal Appeals

- Complex Criminal Litigation

- Ghostwriting Criminal Legal Briefs

Please review the rest of the website to see if our services are right for you.

R v Owston, 2023 SKCA 101

[August 31, 2023] Sexual Assault: Incapacity to Consent [Schwann, Barrington-Foote, McCreary JJ.A.]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Blackout in memory by a complainant in a sexual assault does not mean they did not have capacity to consent to sexual intercourse. This case provides a thorough review of the applicable case law and a procedural map for the decision to be made in such circumstances. Importantly, the analysis ends with the application of the test in a circumstantial case (ie. were there other plausible theories besides non-consent?)

I. INTRODUCTION

[1] This appeal is about a complainant’s capacity to consent to sexual activity and the Crown’s burden to prove lack of capacity beyond a reasonable doubt.

[2] Mitchell Owston was convicted after a trial by judge alone of sexually assaulting the complainant in November of 2017. Mr. Owston and the complainant, who were previously acquainted, met by chance at a local bar. Both were intoxicated, but the complainant was very intoxicated and by 11:00 p.m. the bar refused to serve her any more alcohol. About two and a half hours later, Mr. Owston and the complainant left the bar together in a taxi. The complainant testified that she had no memory of anything that happened from several hours prior to her leaving the bar to the time she woke up the next morning at Mr. Owston’s home. She did not remember socializing with Mr. Owston at the bar or leaving with him. Other witnesses who saw the complainant at the bar testified that she was obviously inebriated – she was slurring her words and had impaired motor skills. The last person who saw the complainant before she left the bar, other than Mr. Owston, was a bouncer, Randy Brandsgaard. He testified that he helped the complainant into a taxi at about 1:30 a.m., asking for and receiving her confirmation that she wanted Mr. Owston to accompany her. Mr. Owston testified that after he and the complainant left the bar, they went to his home and engaged in consensual sex.

[3] Because the complainant had no memory of anything that had happened with Mr. Owston, she later messaged him to ask what had occurred. He told her that they had sexual intercourse without using a condom. Thereafter, the complainant reported to police that Mr. Owston had sexually assaulted her because she did not have the capacity to consent, had no memory of what had occurred and had no intention of having sex with Mr. Owston that night.

[4] The trial judge convicted Mr. Owston of sexual assault. He found that evidence of the complainant’s state of intoxication while at the bar proved that she did not have capacity to consent to sexual activity with Mr. Owston later that night.

[5] Mr. Owston appeals from his conviction. He argues that the trial judge misapplied the test for capacity to consent set out by the Supreme Court of Canada in R v G.F., 2021 SCC 20, 459 DLR (4th) 375 [G.F.]….

[8] The trial judge then considered the inconsistencies in the evidence. He noted that because the complainant had no memory of the key events, including the sexual activity in question, there was little inconsistency between her evidence and Mr. Owston’s….

[9] The trial judge referred to the guidance provided on the issue of credibility in R v W.(D.), [1991] 1 SCR 742 at 757–758 [W.(D.)], determining at the first step of W.(D.) that he did not believe Mr. Owston’s evidence. He determined that it was inconsistent with the evidence of other witnesses and, thus, that his “entire evidence” was neither reliable nor credible (Trial Decision at para 42). In particular, he concluded that Mr. Owston’s credibility was undermined because his evidence about leaving the bar with the complainant differed from that of Mr. Brandsgaard. The trial judge expressly found that Mr. Owston lied when he described how he and the complainant left the bar.

[11] The trial judge summarized his conclusions about the complainant’s capacity as follows:

[127] Capacity, as explained in G.F., requires both awareness and decision-making ability. [The complainant] had some awareness of her surroundings, but she was incapable of coherent thought and rational decision-making. ...

[128] The evidence is overwhelming that [the complainant] had limited comprehension and her reasoning ability was seriously impaired. On the totality of the evidence, I find that she did not have capacity to consent to sexual activity with Mr. Owston. She was not capable of understanding she had a choice to refuse to participate in the sexual activity.

IV. ANALYSIS

A. The trial judge misapplied the test for capacity to consent

[16] A sexual assault occurs when an individual is intentionally touched for a sexual purpose without their consent. Capacity is a precondition to consent. In G.F., the Supreme Court of Canada revisited the framework for assessing whether a complainant has the capacity to consent, setting out a four-part test to determine the answer to that question:

[57] In sum, for a complainant to be capable of providing subjective consent to sexual activity, they must be capable of understanding four things:

- the physical act;

- that the act is sexual in nature;

- the specific identity of the complainant’s partner or partners; and

- that they have the choice to refuse to participate in the sexual activity.

[58] The complainant will only be capable of providing subjective consent if they are capable of understanding all four factors. If the Crown proves the absence of any single factor beyond a reasonable doubt, then the complainant is incapable of subjective consent and the absence of consent is established at the actus reus stage. There would be no need to consider whether any consent was effective in law because there would be no subjective consent to vitiate.

[17] …in G.F., Karakatsanis J., writing for the majority, made it clear that evidence relating to a complainant’s memory, speech or motor skills is not determinative of whether capacity exists:

[65] ... Whether the complainant has a memory of events or not does not answer the incapacity question one way or another. The ultimate question of capacity must remain rooted in the subjective nature of consent. The question is not whether the complainant remembered the assault, retained her motor skills, or was able to walk or talk. The question is whether the complainant understood the sexual activity in question and that she could refuse to participate.

[18] In considering the test for capacity, the Supreme Court expressly adopted a test with a low threshold, initially set out by the Nova Scotia Court of Appeal in R v Al-Rawi, 2018 NSCA 10 at para 60, 359 CCC (3d) 237 [Al-Rawi]. There, the court held that capacity does not require an individual to have the cognitive ability to consider and understand the risks and consequences associated with the sexual activity in question. An operating mind does not need to be able to rationally reason to have capacity.

[20] However, while the trial judge initially stated the law correctly, he ultimately erred in its application. He did not simply advert to incoherent and irrational thinking as relevant evidence; he incorrectly introduced the elements of coherence and rationality into the test for capacity, leading him to conclude, at least in part, that the complainant did not have capacity because she was not capable of rational decision-making. His reasoning is reflected in the following passages:

[127] Capacity, as explained in G.F., requires both awareness and decision-making ability. [The complainant] had some awareness of her surroundings, but she was incapable of coherent thought and rational decision making. This conclusion is supported by the evidence, including the following:

[128] The evidence is overwhelming that [the complainant] had limited comprehension and her reasoning ability was seriously impaired. On the totality of the evidence, I find that she did not have capacity to consent to sexual activity with Mr. Owston. She was not capable of understanding she had a choice to refuse to participate in the sexual activity.

[21] In these key paragraphs, the trial judge states the conclusion that the complainant “had some awareness of her surroundings, but she was incapable of coherent thought and rational decision making”. He then lists the evidence that proves “that conclusion”, which he describes as “overwhelming [evidence] that [the complainant] had limited comprehension and her reasoning ability was seriously impaired” (at paras 127 and 128). He then equates or conflates this with the incapacity to understand she had a choice to refuse to participate in the sexual activity. That constituted error.

[22] Capacity to consent to sexual activity does not require an individual to be able to make rational, logical or reasonable decisions. There is a low threshold to demonstrate capacity in this context, requiring only proof of an understanding of one’s surroundings, the fact that an activity is sexual, the identity of one’s sexual partner(s) and that one can exercise the choice to refuse to participate in the sexual activity.

[23] For these reasons, it is our opinion that the trial judge erred in law by failing to properly apply the law respecting capacity to consent.

[39] A verdict is unreasonable where no properly instructed judge or jury could reasonably have rendered it. It can also be unreasonable where, in a judge-alone trial, the judge draws an inference or makes a finding of fact that is plainly contradicted by the evidence, or is demonstrably incompatible with evidence that is not otherwise contradicted or rejected by the judge Beaudry, 2007 SCC 5, [2007] 1 SCR 190; and R v R.P., 2012 SCC 22 at para 9, [2012] 1 SCR 746. A verdict based on credibility assessments is not unreasonable unless it cannot be supported by any reasonable view of the evidence: R v W.H., 2013 SCC 22, [2013] 2 SCR 180.

[41] …The complainant had no memory of the sexual activity and there were no other witnesses to it. Thus, any conclusion respecting the complainant’s capacity at the time the sexual activity took place had to be inferred from circumstantial evidence, which related primarily to her consumption of alcohol and interactions with other witnesses earlier in the evening.

[43] The evidence from these witnesses suggests that the complainant was intoxicated. It also suggests that she was responsive and oriented. In addition, Ms. Schatz’s and Mr. Brandsgaard’s last interactions with the complainant, at about 10:30 p.m. and 1:30 a.m. respectively, demonstrate that the complainant was able to, and did, make decisions about being in Mr. Owston’s company. She communicated those decisions clearly to Ms. Schatz and Mr. Brandsgaard. Security video from the bar also confirmed that, including showing her linking arms with Mr. Owston and walking through the bar.

[44] There was one other aspect of the evidence that is relevant in this context. The complainant had been dropped off at the bar and had expected to be picked up by a man she had been dating for several months. She testified that there was “no scenario” in which she would have gone home and had sex with Mr. Owston, and that she would not have had sex with Mr. Owston or anyone else without a condom. In R v Al-Rawi, 2018 NSCA 10, 359 CCC (3d) 237, Beveridge J.A. made this point:

[70] Where a complainant testifies that she has no memory of the sexual activity in question, the Crown routinely asks: “Would you have consented?” Despite the potential to discount the typically negative response as speculation, the answer is usually received into evidence, and depending on the reasons, may or may not have a bearing on the determination if consent or capacity to consent were absent (see for example: R. v. J.R. [(2006), 40 CR (6th) 97, aff’d 2008 ONCA 200, 59 CR (6th) 158, leave to appeal to SCC denied, 2008 CanLII 39173/39174]; R. v. B.S.B., [2008 BCSC 917, aff’d 2009 BCCA 520, 71 CR (6th) 306]; R. v. Olutu, [2016 SKCA 84, 338 CCC (3d) 321, aff’d 2017 SCC 11, [2017] 1 SCR 168]; R. v. Meikle, [2011 ONSC 650, 84 CR (6th) 172] at para. 45; R. v. Tariq, [2016 ONSC 614, 343 CCC (3d) 87] at para. 70; R. v. Esau, [[1997] 2 SCR 777] at paras. 4 and 91; R. v. Kontzamanis, [2011 BCCA 184] at para. 31). For unknown reasons, this question was not put to the complainant.

[45] Justice Rouleau made the same point in relation to capacity to consent R v Garciacruz, 2015 ONCA 27, 320 CCC (3d) 414 [Garciacruz]:

[69] In the absence of direct evidence on the issue of consent, a court can draw inferences from a complainant’s pre-existing attitudes and assumptions regarding the period during which she has no recollection. In appropriate cases, the court can conclude that the complainant must have been incapable of consenting at the time of the sexual interaction because, had she been capable of consenting, she clearly would have refused to consent. This type of inference would support the trial judge’s finding of that the complainant was asleep and incapable of consenting.

[46] In R v Olotu, 2016 SKCA 84, 338 CCC (3d) 321, aff’d 2017 SCC 11, [2017] 1 SCR 168, Jackson J.A. accepted this principle, but added an important cautionary note, commenting as follows:

[58] ... In a case where the complainant lacks memory of the event, the complainant’s testimony that she would never have agreed to sexual intercourse must be handled with care for the very reason Mr. Olotu articulates in this case. Such evidence can shift the burden of proof. It is evidence that is difficult for an accused to refute or overcome because countervailing evidence directed to determining whether the complainant would have engaged in the sexual act will usually be inadmissible.

[48] Evidence that could support a complainant’s testimony that they would not have consented depends on the facts. In R v Le Goff, 2022 ONSC 609, Presser J. offered the following comments in relation to this issue:

[175] Courts have entertained evidence from a complainant that she “would not have” consented as circumstantial evidence of capacity and of actual consent on numerous occasions: Garciacruz, at paras. 30, 69–70; J. R., at paras. 25–28; Tariq, at paras. 69–70; R. v. Kontzamanis, 2011 BCCA 184, at para 31. The weight assigned to this circumstantial evidence, and the strength of the inferences that will be drawn from it, often depend on:

- whether there is other evidence supporting the complainant’s testimony about what she would not do: see, for example, [R v Mugabo, 2019 ONSC 4308], at para 75; R. v. Carpov, 2018 ONSC 6650, at para. 90; R. v. Olotu, 2016 SKCA 84, at paras. 59–60, aff’d 2017 SCC 11;

- whether there was evidence of the complainant’s actions that contradicted her testimony about what she would not do: see, for example, Garciacruz, at paras. 77, 80–81; [R v Meikle, 2011 ONSC 650, 84 CR (6th) 172], at para. 43; and

- whether the complainant had specific and compelling reasons for which she said she would not have consented or whether her evidence that she would not have consented depended on her general attitudes, character, or personal code of conduct: see, for example, J.R., at paras. 31–35.

[50] This emphasis on the importance of evidence that could be found to increase the probative value of a complainant’s assertion that they would not have consented reflects the principle that a trial judge must consider all the evidence when deciding if the Crown has proven guilt beyond a reasonable doubt (see, for example, R v Morin, [1988] 2 SCR 345 at 379). It also accords with the requirement that, as Cromwell J. wrote in R v Villaroman, 2016 SCC 33 at para 55, [2016] 1 SCR 1000, “[w]here the Crown's case depends on circumstantial evidence, the question becomes whether the trier of fact, acting judicially, could reasonably be satisfied that the accused's guilt was the only reasonable conclusion available on the totality of the evidence”. This test reflects the criminal standard of proof; that is, “[i]f there are reasonable inferences other than guilt, the Crown's evidence does not meet the standard of proof beyond a reasonable doubt” (at para 35).

[51] In order to answer this question, trial judges must “consider ‘other plausible theor[ies]’ and ‘other reasonable possibilities’ which are inconsistent with guilt”, being theories or reasonable possibilities “based on logic and experience applied to the evidence or the absence of evidence, not on speculation” (Villaroman at para 37). While “the line between a ‘plausible theory’ and ‘speculation’ is not always easy to draw ... the basic question is whether the circumstantial evidence, viewed logically and in light of human experience, is reasonably capable of supporting an inference other than that the accused is guilty” (at para 38). The standard of review that applies when a verdict based on circumstantial evidence is challenged as being unreasonable is that described in R v Power, 2022 SKCA 24, [2022] 10 WWR 263; that is, “the question for an appellate court is whether the trier of fact, acting judicially, could reasonably have been satisfied that the guilt of the accused was the only reasonable conclusion available on the evidence taken as a whole” (at para 75. See also: Villaroman at para 55; R v Groshok, 2019 SKCA 39 at para 40; and R v Murillo, 2023 SKCA 78 at paras 25 and 26). The question in this case, accordingly, is whether the trial judge could reasonably have been satisfied that the only reasonable inference that could be drawn from the evidence as to the complainant’s consumption of alcohol and her actions before she left the bar with Ms. Owston, together with her testimony that she would not have had sex without a condom, was that the complainant lacked the capacity to consent at the time she had intercourse with Mr. Owston.

[52] In our respectful view, the trial judge could not reasonably have been satisfied that was the only reasonable conclusion about the complainant’s capacity. While the complainant was obviously inebriated at the bar, Mr. Brandsgaard described her as “manageable”. His evidence, like that of Mr. Reid and Ms. Schatz, suggests that her level of intoxication was not entirely debilitating. While her speech and motor skills were impaired, and she had difficulty texting and using her phone, there was also evidence that the complainant was responsive to conversation, knew where she was and with whom she was socializing. As well, the evidence demonstrates that she made multiple simple decisions throughout the evening; including declining Mr. Brandsgaard’s offer of a taxi ride home on several occasions (even when a paid ride was offered); alternatively accepting and declining Mr. Brandsgaard’s offers of water; and telling Ms. Schatz that she wanted to keep socializing with Mr. Owston despite Ms. Schatz raising concerns about the complainant’s boyfriend.

[53] It is particularly striking that Mr. Brandsgaard’s final interaction with the complainant when she left the bar consisted of her telling him directly that she understood Mr. Owston was with her in the taxi, that she was fine with him being there, and that he knew where they were going. This was direct evidence that, at the time she left the bar, the complainant knew where she was and who she was with, and that she was capable of making a choice. That evidence is, together with the other evidence accepted by the trial judge, circumstantial evidence that would support the reasonable inference that both when she left the bar and when she and Mr. Owston had intercourse, she was capable of understanding the physical act; that the act was sexual in nature; who Mr. Owston was; and that she had the choice to refuse to participate in the sexual activity.

[54] The complainant’s propensity evidence that she would not have had sex with Mr. Owston without a condom adds nothing of significance to this analysis. There was, for example, no evidence that the complainant considered Mr. Owston to be repulsive or, leaving aside her general assertion that she would not have had sex with anyone without a condom, that he could not have been an acceptable sexual partner. She did not seek to avoid him. To the contrary, she chose to be in his company for an extended period despite the intervention of her friend, and ultimately, to voluntarily leave with him.

[55] Further, and importantly, she was intoxicated, and as courts have repeatedly recognized, intoxication can lead people to do things and make choices that they would not have made if they were sober. In Garciacruz, for example, the complainant, who had been drinking, testified that she had little memory of the events leading to the alleged sexual assault. Justice Rouleau dealt with her evidence that she would not have had consensual sex with the accused as follows:

[77] First, there was evidence which gave reason to doubt the complainant’s assertion that because of her code of behaviour, she would never have consented to intercourse with the appellant. The complainant testified that she “would never have hung out [alone] with a married man.” This assertion by the complainant was clearly contradicted by the facts of the case. It was the complainant who invited herself to the appellant’s house for wine and guacamole when she knew that the appellant’s wife was out of town. Not only was the complainant wrong in her evidence that she would never spend time alone with a married man, but she had done so that very day with the appellant, the husband of her friend.

[78] Second, without some explanation as to the cause and nature of the blackout condition, it is difficult to conclude, without more, that if she had been in the blackout state, the complainant’s “lack of romantic or sexual attraction to [the appellant], her own code of behaviour and her friendship with [the appellant’s wife]” would govern her actions.

[56] For these reasons, it is our respectful opinion that the trial judge could not reasonably have been satisfied that the only reasonable inference that could be drawn from the evidence was that the complainant lacked capacity when the sexual activity occurred. As such, the finding of guilt on that basis was unreasonable as it could not be supported by the evidence. It must be quashed.

VI. CONCLUSION

[60] The appeal is allowed, the conviction quashed, and an acquittal entered.

R v Hess and Profetto, 2023 ONSC 3065

[May 23, 2023] Charter s.8: Warrant Challenge - Staleness and Stereotypes about Drugdealers [Howard J.]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: The investigation here focused on a third party. The accused interaction with that party led to inferences regarding their possession of drugs within the ITO that was executed on a residence associated to Ms. Hess. The key takeaways are that minimal observations of exchanges (even with people reasonably believed to be drug dealers) does not mean the target was involved in a drug deal, the connection of drugs to a residence needs to be firmly established in time (not stale information - 3 weeks is too long, with a need for observations of a transfer into the home) and evidence of occupation (observations of entry/exit, evidence of ownership). Stereotypes of what drug dealers do and where they store drugs does not suffice to fix problems with deficiencies in the above.

Overview

[1] On a thirty-count indictment dated December 22, 2020, the accused, Ms. Danielle Deanne Hess and Mr. Sebastiano Vince Profetto, were charged with a variety of drugs and weapons offences.

[5] The accused brought a number of applications. In particular, they challenge the search warrant that led to the charges. They apply for an order finding that their rights guaranteed under s. 8 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms8 to be free from unreasonable search and seizure have been violated and for an order pursuant to s. 24(2) of the Charter excluding from admission into evidence at trial all evidence that was obtained by the police as a result of the alleged breach of their Charter rights.

Factual Background

[7] As Mr. Pollock for the Crown observed, counsel for the accused and counsel for the Crown more or less agree on the factual narrative and relevant chronology for present purposes.

[8] That said, I think it important to highlight some background context.

[9] The critical events in question date back to June 2019.9

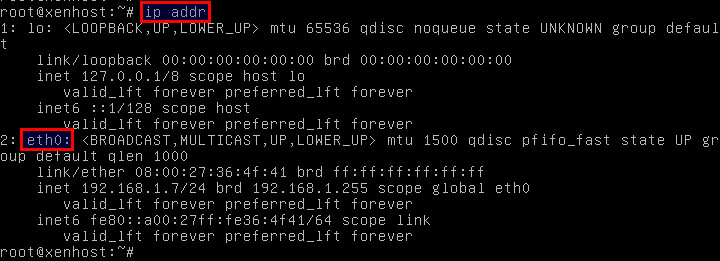

[10] The charges before the court initially arose out of a broader investigation of drug trafficking in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) conducted by the Toronto Police Service (TPS), which was named “Project Oz.”

[11] The main target of Project Oz was one Mr. Christopher Janisse, who resided in the City of Toronto and was believed to be a high-level drug trafficker.

[12] The charges in Windsor arose after certain surveillance activity was conducted by TPS officers on June 4, 2019. On that day, TPS officers observed Mr. Janisse exit the underground parking garage associated with his residence in Toronto, driving his black Mazda motor vehicle. TPS officers followed Mr. Janisse’s vehicle as he travelled from Toronto to the Town of Tilbury, a community in the Municipality of Chatham-Kent, about 50 km. east of Windsor.

[13] On that same June 4th day, while in Tilbury, TPS officers observed Mr. Janisse having some apparent interactions with a female driver of a red-coloured, Ford pickup truck. TPS officers then followed the red Ford pickup as it travelled to Windsor and ultimately parked at the residential premises municipally known as 372 Crawford Avenue in Windsor.

[14] Police subsequently formed the belief that the female driver observed driving the red Ford pickup and attending the 372 Crawford Avenue residence was Ms. Hess.

[16] On the morning of Thursday, June 27, 2019, various WPS officers were briefed by Sgt. Gannon of the DIGS Unit.

[17] The officers were advised that TPS authorities had obtained a search warrant issued on June 27, 2019, pursuant to s. 11 of the CDSA, which had been obtained on the basis of an information to obtain (ITO) sworn June 26, 2019, for the search of the residential premises at 372 Crawford Avenue and the red Ford pickup associated with Ms. Hess, who was identified as a target. The officers were also advised that Ms. Hess was associated with a Mr. Sebastiano Profetto. It was believed that ESU should be involved because of previous dealings of the WPS with Mr. Profetto.

[18] The assembled officers were advised by Sgt. Gannon, by way of the TPS officers, that they had grounds to arrest for conspiracy to commit indictable offence, possession of proceeds obtained by crime, and possession of a controlled substance for the purpose of trafficking. However, on the evidence of P.C. Pope, it was made clear to the officers that, at that point, they had no grounds to arrest Mr. Profetto.

[19] … Ms. Hess was arrested on scene at the convenience store at 5:18 p.m.

[21] As a result of the execution of the CDSA search warrant at the 372 Crawford residence, WPS officers discovered and seized a number of items that form the subject-matter of the charges before the court.

[22] Pursuant to a residential lease agreement dated March 25, 2018, the residential premises at 372 Crawford Avenue were leased to Mr. Profetto and one Amanda Lee Martin. Ms. Hess is not named in the lease. Ms. Martin took no part in the instant proceeding.

[23] An arrest warrant was subsequently executed on Mr. Profetto.

Analysis

Were the accused denied their rights to be free from unreasonable search and seizure under s. 8 of the Charter?

[31] Or, as stated most recently by our Court of Appeal in R. v. Jones:

To issue a warrant under s. 11(1) of the CDSA, the ITO’s contents must satisfy the authorizing justice that there are reasonable grounds to believe an offence has been committed and that evidence of that offence will be found at the place to be searched. The ITO need not conclusively establish the commission of an offence nor the existence of relevant evidence. “Reasonable grounds” is a standard of credibly-based probability [citation omitted.] The authorizing justice is permitted to draw inferences, so long as the inferences of criminal conduct and recovery of evidence are reasonable on the facts disclosed in the ITO [citation omitted].14

[32] In reviewing an ITO, the following principles must also be borne in mind:

a. The ITO must be read as a whole.15

b. A reviewing court’s analysis of the evidence should be contextual as opposed to piecemeal.16

c. The ITO must be read in a common-sense manner, having regard for its author. Police officers are not legal draftspersons and should not be held to that standard.17

d. The issuing justice is entitled to rely on affiant opinions.18

e. Officer training and experience may be relevant in determining whether the requisite legal standard for a search has been met.19 However, courts are not required to uncritically accept or defer to a police officer’s conclusion just because it is grounded in their experience and training.20

f. “That an item of evidence in the ITO may support more than one inference, or even a contrary inference to one supportive of a condition precedent, is of no moment.”21

g. Reasonable grounds must be assessed based on the totality of the circumstances, including the nature of the police investigation.22

[34] For present purposes, the relevant provisions of the ITO include the following:

a. In para. 3 of the ITO, D.C. Wilson identifies six persons, including Mr. Janisse and Ms. Hess, who, he says in para. 5, “have all been seen meeting with JANISSE and engaging in behaviour that is consistent with drug trafficking.”

b. Paragraph 3 of the ITO does not list Mr. Profetto.

c. In para. 3(a) of the ITO, D.C. Wilson indicates that the residential address of Ms. Hess is 636 Hildegarde Street, Windsor, Ontario.

e. In para. 42 of the ITO, D.C. Wilson sets out the observations made on June 4, 2019, when Mr. Janisse travelled to Tilbury and encountered a female person believed to be Ms. Hess, as I have referenced above.

g. In paras. 42(c) and (d), D.C. Wilson states that:

At approximately, 2:00pm, JANISSE met with an unknown female, later identified as Danielle HESS born December 8, 1969, who was driving a Ford truck bearing Ontario license plate AZ98201. JANISSE and HESS travelled in their respective vehicles in tandem around several side streets and dead-end streets before stopping on Young Street.

At that time, JANISSE retrieved a weighted black duffle bag from the passenger side of his Mazda and placed it in the rear passenger seat of HESS’ truck. At the same time, HESS retrieved a brown cardboard box approximately 2’x2’x2’ in size from the rear driver’s side area of her truck and handed it to JANISSE. JANISSE took the cardboard box and attempted to put it into the trunk of his Mazda but the box would not fit so JANISSE placed the box in the rear passenger area of his Mazda. JANISSE and HESS then parted ways.

h. D.C. Wilson added, intra alia, the following commentary after para. 42(d):

[In my experience as a drug investigator, mid-to-high level drug traffickers need and rely on bags to move/traffic their illicit substances. Bags can conceal and transport large amounts of drugs and/or money without attracting attention. Furthermore, the meetings and visits which have been short in duration are consistent with illicit behaviour (such as drug trafficking).]

i. In paras. 42 (e) and (f), D.C. Wilson recounted how the surveillance followed Ms. Hess to Windsor, as follows:

Surveillance was continued on HESS in the Ford truck who attended the Windsor area. HESS was misplaced for a short period of time, and once relocated, was followed to a house located [at] 372 Crawford Avenue, Windsor.

HESS met with an unknown male later identified as Sebastiano PROFETTO born November 10, 1988, and the two attended the rear area of the residence.

j. In paras. 42(g) to (l) of the ITO, D.C. Wilson reviewed certain observations, which he then summarized in para. 90 of the ITO as follows:

Surveillance was continued on HESS and she was later observed meeting with an unknown male which was consistent with a street level drug transaction – based on her driving behaviour (circling the neighbourhood), waiting for 15 minutes for an unknown male that got into her passenger seat, drove that unknown male two blocks away and then let him out of her vehicle.

k. In para. 92 and again in para. 163, D.C. Wilson noted that Ms. Hess has two drug- related convictions, which date back to March 2012.

m. In para. 169, D.C. Wilson concludes that, “[b]ased on the information contained above, I believe that I will locate the items set out in Appendix “A” [i.e., controlled drugs, trafficking materials, proceeds of drug trafficking, records, and electronic devices] inside the above address and vehicle”, i.e., the 372 Crawford residence and the red Ford truck.

[35] As an aside, I note what D.C. Wilson did not say in the ITO. In particular:

a. Nowhere in the ITO did the officer assert that Ms. Hess resides at the 372 Crawford residence…

b. After the observations of June 4, 2019, there is no reference to any later activities of Ms. Hess and Mr. Profetto in the balance of the 103-page ITO…

c. Nowhere in the ITO is there any recorded observation that either Ms. Hess – or Mr. Profetto for that matter – ever entered the 372 Crawford residence….

d. Nowhere in the ITO is there any recorded observation that the “weighted black duffle bag” that Mr. Janisse was seen placing in the rear passenger seat of Ms. Hess’s truck in Tilbury was ever seen being carried into the 372 Crawford residence….

[36] I have a number of concerns regarding the ITO in the instant case.

[37] First, D.C. Wilson asserted, in para. 169, that based on the information set out in the ITO, he believes that he will locate items such as controlled drugs, trafficking materials, proceeds of drug trafficking, records, and electronic devices, at the 372 Crawford residence. That belief was based, in large part, on his assertion, set out in para. 11 of the ITO, that based on all the sources of information collected in the course of the Project Oz investigation, Ms. Hess, and Mr. Janisse and the others named in para. 3, “are trafficking controlled substances throughout the Greater Toronto Area.”

[38] However, insofar as Ms. Hess is concerned, there is nothing set out in the ITO (or otherwise) that supports that assertion. There is nothing that places Ms. Hess in the GTA. The evidence concerning Ms. Hess in the ITO places her in Tilbury and Windsor only. Being completely unsupported by any facts set out in the ITO (or otherwise), the affiant’s assertion that Ms. Hess was currently trafficking in the GTA is simply false or, at the very least, misleading.

[39] I agree with Mr. Miller’s submission that this “falsehood was critical evidence in the ITO in the issuing of the search warrant because it forged a link between the one isolated transaction on June 4[th] and the presence of controlled substances and the other things in the search warrant in the [372 Crawford] residence for which the warrant was issued.”

[40] In my view, it is clear that the assertion in para. 11 of the ITO as it applies to Ms. Hess must be excised.

[44] … As Nakatsuru J. said in Downes, which applies equally to the impugned ITO in the instant case, “a significant piece of context for the ITO is the ample grounds to believe that Mr. Janisse was a high level drug trafficker. Further, Mr. Janisse’s modus operandi appears to be brief vehicle meetings with others where exchanges of bags or boxes take place.”24 But the credible and probable fact that Mr. Janisse conducted drug exchanges does not necessarily mean that the interaction between Mr. Janisse and Ms. Hess on June 4th in Tilbury was one such drug transaction. The specifics of that interaction must be considered.

[47] As such, in my view, the following commentary of Nakatsuru J. in the Downes case applies with equal force to the circumstances before me here. In Downes, Nakatsuru J. recognized that what matters is whether “the ITO provides reasonable grounds to believe that the evidence relating to the offences would be found in the searches,”26 and he then went on to say:

That recognized, the core frailty of the ITO in relation to the places D.C. Wilson sought to search is that, on an objective assessment of the totality of the circumstances, it cannot be inferred that the meeting on June 21 between Mr. Medeiros and Mr. Janisse was a drug transaction. This is just speculation, and it is unsupported by other information in the ITO, which as a whole does not provide grounds to believe that drug related evidence could be found in the residence, locker, or car.

Innumerable possible explanations can be posited about why Mr. Medeiros met with Mr. Janisse on June 21. The crucial point is that little evidence supports it was for a drug deal. Stripped to its essence, the evidence is that Mr. Medeiros, carrying his backpack, met with Mr. Janisse, who gave him a lift to his Mustang in the underground garage of a neighboring condominium where it had been parked about 30 minutes earlier. They did not stay together in that underground for any length of time. Even when considered in the context of all the other transactions Mr. Janisse was involved in, this cannot lead to a reasonable inference that a drug deal took place.

Carrying the analysis forward, such a meeting therefore cannot support a credibly based probability that evidence of the listed offences could be found in the places linked to Mr. Medeiros. To conclude otherwise would rely at least in part on stereotypical thinking about the behaviour of drug traffickers, who they associate with, and how: James, at paras. 21-25. Like everyone else, drug dealers can have innocent interactions with others. It would be a stretch, to say the least, to assume that everyone a drug dealer interacts with is necessarily buying or selling drugs. All the grounds put forth culminate in suspicion and conjecture but cannot reach the threshold of reasonable and probable grounds: Morelli, at para. 63.

Stereotypical thinking also seems to have infected D.C. Wilson’s assessment of Mr. Medeiros’ dated 2011 convictions for firearm offences. He averred that in his experience it is not uncommon for drug dealers to carry or possess weapons for protection. While such an association does regularly exist, the missing link is any evidence that Mr. Medeiros was or is a drug dealer.27

[48] In my view, the analysis of Nakatsuru J. in Downes – even though dealing with a different ITO – applies equally to the circumstances of the instant case. The same commentary about the “weighted” backpack in Downes applies with equal force to the “weighted black duffle bag” in our case. The meeting between Mr. Janisse and Ms. Hess in Tilbury did share some suspicious similarities to meetings that Mr. Janisse had with others, but innumerable possible explanations can be posited about why Mr. Janisse met with Ms. Hess in Tilbury on June 4, 2019. Such a meeting therefore cannot support a credibly based probability that evidence of the offences in question could be found in the places linked to Ms. Hess and, in particular, the 372 Crawford residence.

[49] At the end of the day, the assertion of D.C. Wilson as to the observed singular interaction between Mr. Janisse with Ms. Hess in Tilbury on June 4, 2019, is just speculation, and it is unsupported by other information in the ITO, which as a whole does not provide grounds to believe that drug-related evidence could be found in the 372 Crawford residence.

[50] Thirdly, the connection of all of these events to the 372 Crawford residence is somewhat tenuous at best. Obviously, on the basis of the information that was set out in the ITO, D.C. Wilson drew an inference that, while in Tilbury, Ms. Hess was provided with a “weighted black duffle bag” that contained illicit drugs or other substances. And, he averred, Ms. Hess then travelled to the driveway of the 372 Crawford residence, where she met Mr. Profetto. Subsequently, both were seen to leave the area of the home and met with third persons. However, neither Ms. Hess nor Mr. Profetto were ever seen to enter the 372 Crawford residence. And more to the point, the “weighted black duffle bag,” which figured so prominently in the drug-related inferences that D.C. Wilson drew, was never seen entering the 372 Crawford residence. Indeed, after its very brief sighting in Tilbury on June 4th, the “weighted black duffle bag” was never seen again insofar as the ITO is concerned. In terms of the evidence set out in the ITO, there is really no connection between the “weighted black duffle bag” and the 372 Crawford residence at all. On the basis of the information… [Emphasis by PJM]

[52] My fourth concern relates to the staleness of the information and observations recorded in the ITO. As I have said, the only instance of the alleged involvement of Ms. Hess and Mr. Profetto with the Project Oz investigation took place on June 4, 2019. After June 4th, there is nothing that implicates Ms. Hess, Mr. Profetto, or the 372 Crawford residence. [Emphasis by PJM]

[53] The ITO was sworn by D.C. Wilson three weeks later, on June 26, 2019. The search warrant, based on the information set out in the ITO, was issued on June 27, 2019 – more than three weeks after the only observed incident involving Ms. Hess, Mr. Profetto, and the 372 Crawford residence.

[54] There was no reference to Ms. Hess, Mr. Profetto, or the 372 Crawford residence after the incident of June 4, 2019. There was no updated surveillance information set out in the ITO as might satisfy the issuing justice that the drug-related activities observed on June 4, 2019, allegedly involving Ms. Hess and Mr. Profetto, were continuing to occur as of June 26 or 27, 2019.

[55] In James, our Court of Appeal held that the fact that the appellant had sold drugs to someone in his vehicle [on December 18, 2015] 23 days prior to the execution of a search warrant on February 26, 2016, did not establish that reasonable and probable grounds to believe that drugs or drug paraphernalia would be found in the vehicle at the time of the search. The court held that:

Information in the ITO establishes that the respondent might have been involved in a drug transaction on December 18, 2015[,] and provides a reasonable basis to believe that he delivered drugs to MD on February 3, 2016. However, I agree with the trial judge that this information is insufficient to allow a justice to find a pattern of drug dealing or to support the conclusion that there was sufficient credible and reliable evidence to establish reasonable and probable grounds to believe that evidence, drugs or paraphernalia would be found in the car at the time of the search on February 26, 2016.28

[56] Similarly, I am satisfied that the recorded observations in the ITO as to the alleged events on June 4, 2019, do not provide reasonable and probable grounds to believe that evidence, drugs, or drug paraphernalia would be found in the 372 Crawford residence 23 days later when the search warrant was issued on June 27, 2019.

[58] In sum, I conclude that the ITO does not meet the standard of a credibility-based probability. I find that the issuing justice could not have properly granted this search warrant given the lack of reasonable and probable grounds that drugs and other associated evidence could be found at the 372 Crawford residence. As a result, I further find that the subsequent search of the 372 Crawford residence pursuant to the flawed search warrant was unlawful.29 It was essentially a warrantless search.30 A warrantless search is prima facie unreasonable, and thus contrary to s. 8 of the Charter.31 The Crown has not met its onus of demonstrating on a balance of probabilities that the warrantless search was reasonable

[59] I therefore find a violation of the accused’s rights as guaranteed by s. 8 of the Charter.32

[87] In my view, the high privacy interest in a residential dwelling home and the significant impact on that interest that is caused by an improvidently-obtained search warrant and an unlawful, warrantless search cumulatively favour exclusion of the evidence, rather than admission. Our Court of Appeal has held that “the regular admission of evidence obtained from people’s homes, where there is not a proper basis for a search, would bring the administration of justice into disrepute.”66 I agree with Mr. Miller’s submission that, in the long term, the impact of the routine admission of this type of evidence in the teeth of these type of breaches exacts too heavy a price to the repute of the administration of justice.

[88] In the result, the evidence obtained from the warrantless search of 372 Crawford residence must be excluded.

[89] Without the impugned evidence, the charges against both accused must be dismissed. It is so ordered.

R v AL, 2023 ABKB 505

[September 6, 2023] SOIRA Exemption [Peter Michalyshyn J. ]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: This case provides a great overview of the law supporting SOIRA exemption applications in relatively minor sexual offences. No expert evidence is required.

Introduction

[1] This is the offender AL’s application to be exempted from the mandatory application of the Sex Offender Information Registration Act (SOIRA) SC 2004 c 10. For reasons which follow the application is allowed.

Background

[2] AL was sentenced on June 15, 2023 for the offence of unlawfully touching for a sexual purpose, contrary to s 151 of the Criminal Code. As set out more fully in R v AL, 2023 ABKB 374, AL plead guilty and was sentenced to 18-months to be served in the community pursuant to a Conditional Sentence Order.

[3] The offence, while still serious, was clearly the least grave as compared to the many parity cases before the court. The offence was also of an isolated nature. That conclusion stemmed from the unique facts and from an August 5, 2022 expert report which concluded there was little if anything in AL’s sexual and relationship history to suggest he was a sexually deviant offender. Test outcomes supported the conclusion he posted a low risk of sexual recidivism. Further support for low recidivism risk included his strong remorse and victim empathy. To the extent the offence was the product of compromising medical illness and/addition, AL had taken steps to address both. And both his 18-month conditional sentence and subsequent 12-month period of probation included further assessment and treatment requirements.

The law governing a SOIRA exemption

[7] As to the effect of Ndhlovu, little more needs to be added to what has already been articulated in the Alberta decision of R v KS, 2023 ABKB 363 at paras 77-85 (cited too in R v Sulub, 2023 ABKB 431).

[9] On the merits, again as noted in KS, citing Albashir and R v Shokouh, 2023 ONSC 1848 at para 23, a s 24(1) Charter remedy may be available even during the period of suspension if the offender can demonstrate that application of the legislation found to be constitutionally infirm would be a breach of his own Charter rights, and if granting an individual remedy would not undermine the purpose of suspending the s 52(1) declaration.

Grossly disproportionate

[12] In a decision dealing with the pre-2011 SOIRA regime, the court in R v Redhead, 2006 ABCA 84 articulated the following approach to the question of gross disproportionality (at paras 20, 26, 28-33, citations omitted):

[20] The test to determine whether the exception in s. 490.012(4) applies is: whether the impact of a SOIRA order on the liberty and privacy interests of a convicted sex offender would be grossly disproportionate to the public interest of effectively investigating crimes of a sexual nature. Thus, the court must assess the impact of a SOIRA order on the offender, including the impact on his or her privacy and liberty interests and determine whether that impact is grossly disproportionate to the public interest.

...

[26] Under s. 490.012(4), the offender bears the evidentiary burden of establishing that the impact of a SOIRA order on him or her would outweigh the public interest in protecting society by investigating crimes of a sexual nature.

...

[28] The assessment of how reporting obligations might disproportionally impact an offender requires an evidentiary foundation. The focus of that inquiry must be on the offender’s present and possible future circumstances, and not on the offence itself.

[30] Thus, the analysis under s. 490.012(4) is restricted to the impact of a SOIRA order on the offender. Nevertheless, that subsection clearly contemplates that factors other than the offender’s privacy and liberty interests may be considered, as it requires the court to consider the impact on an offender, including any impact on the offender’s privacy and security interests.

[31] Other factors might include unique individual circumstances such as a personal handicap, whereby the offender requires assistance to report. Courts have also considered the intangible effects of the legislation, including stigma, even if only in the offender’s mind; the undermining of rehabilitation and reintegration in the community; and whether such an order might result in police harassment as opposed to police tracking.

[33] However, given the onus on the offender to demonstrate why the impact of such an order would be disproportional to the public interest, it appears there is no presumption of impact in the legislation arising from the length of reporting obligations alone. Patently, the impact on anyone who is subject to the reporting requirements of a SOIRA order is considerable. But absent disproportional impact, the legislation mandates that anyone convicted of a prescribed offence is subject to the prescribed reporting period.

[13] Since the 2022 decision in Ndhlovu, some cases have concluded similarly that an applicant must show something more than the SOIRA regime’s significant deprivation of liberty already noted in Ndhlovu. An example is R v CRJ, 2023 BCSC 1151 at para 109:

[14] On the other hand, in R v Shokouh, 2023 ONSC 1848, at para 20, the court concluded it remained an open question whether the reporting requirements themselves could, in certain circumstances, be grossly disproportionate. The court cited Ndhlovu, are para 116:

[15] In any event, also post-Ndhlovu, courts have generally cautioned that the standard for gross disproportionality is “stringent” (R v JS, 2023 MBKB 26 at para 13; R v OR, 2023 MBKB 32 at para 14) and “stringent and demanding” (R v Capot Blanc, 2023 NWTTC 7, at para 54).

Bears no connection

[16] Registration under SOIRA will bear no relation to the purposes of the registration regime – which are to assist police in preventing and investigating sexual offences – if offenders can show they are persons who pose no increased risk of reoffending in the future. Such individuals who pose no increased risk are those who the court in Ndhlovu called the “lowest risk sex offenders” (at para 92):

[91] The expert evidence, which the sentencing judge accepted, made clear that there is no perceptible difference in sexual recidivism risk at the time of sentencing between the lowest-risk sexual offenders — the bottom 10 percent — and the population of offenders with convictions for non-sexual criminal offences. In both instances, about two percent of individuals — whether they be the lowest- risk sexual offenders or the people with a criminal record unrelated to a sexual offence — commit a sexual offence over the next five years.

[92] Mandatory registration is overbroad to the extent it sweeps in these lowest‐risk sex offenders. As a result of their risk profile, there is no connection between subjecting them to a SOIRA order and the objective of capturing information that may assist police prevent and investigate sex offences because they are not at an increased risk of reoffending. The purpose of the provision is not advanced by including these offenders.

[17] The court in Ndhlovu goes on to say that while the commission of a sexual offence “is one of many empirically validated predictors of increased sexual recidivism”, relevant too are other factors such as age, unusual or atypical sexual interests, sexual preoccupation, lifestyle instability or poor cognitive problem solving, amongst others. Further:

[94] ...Recidivism risk also varies depending on the pattern of offences: for instance, whether the offence is a non‐contact sexual offence, or whether it is committed against a child, a stranger, an acquaintance or a family member. Yet the expert evidence makes clear that valid risk assessments must consider a range of risk relevant variables — there is no single factor that, on its own, yields an offender’s recidivism risk. In short, many factors affect a sex offender’s recidivism risk.

Expert evidence

[22] The court in Sulub, at para 71, noted that no expert evidence was before it regarding the offender’s risk to reoffend, and none was required:

[71] For the Offender to obtain the benefit of a SOIRA order exemption, it is not absolutely necessary that he demonstrate that he falls within the lowest 10% in terms of sexual recidivism risk or otherwise have personal characteristics that make him less likely to reoffend. These are simply examples used in Ndhlovu to establish overbreadth. The question is whether, for the Offender, the deprivation is in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice. In other words, is a mandatory SOIRA order for the Offender arbitrary or overly broad?

[24] In R v TS, 2023 ABKB 157 no expert evidence was before the court. TS is a decision coming out of a Summary Conviction Appeal. It uniquely involved a sentencing in the first instance in which a SOIRA application was intended but never made or at least decided. The SCA judge agreed with the unopposed application before her that it was appropriate to exempt the offender from SOIRA registration. The record was also of an offender who the sentencing judge had found was unlikely to reoffend. As such, the SCA judge concluded there was no connection between subjecting the offender to a SOIRA order and the objective of capturing information about offenders that may assist police in preventing and investigating sex crimes: Ndhlovu at para 141.

The exemption application in AL’s case

[36] There is no serious issue that in AL’s case registration under SOIRA amounts to a deprivation of liberty. The real question is whether the deprivation is in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice: Sulub, at paras 66-67. In other words, has AL shown that his inclusion on SOIRA would be “grossly disproportionate to” the purpose of the regime, or would “bear no relation” to those purposes.

Grossly disproportionate

[37] The Crown points to a lack of evidence to support a finding of gross disproportionality, and I agree.

Bears no relation

[38] I find that on the record before me AL has proven he is an offender who is not at increased risk to reoffend. He is thus entitled to a SOIRA exemption.

[39] I note that in her written submissions, counsel for the Crown submits that the applicant must prove on the basis of expert evidence that his statistical recidivism risk is no higher than for non-sexual offenders. However, as noted earlier in these reasons, I have rejected that expert or statistical evidence is absolutely required in every case.

[42] I agree rather with the observation in Sulub, at para 71, that Ndhlovu referred to numerous examples of overbreadth, but did not limit how courts may conclude, on the record before them with or without expert or statistical evidence. The only question is whether, for the offender, the deprivation is in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice. The answer is reached through an inquiry into “the personal circumstances” of the offender –whether, on the whole, they are at no increased risk of reoffending: Ndhlovu, at para 87. The lone example of a disabled offender that follows, at paras 88-89 of Ndhlovu, does not limit the reach of the court’s earlier general guidance, either at para 87, or as noted above, at paras 91-95.

[43] In her written submissions counsel for the Crown takes issue with AL’s August 5, 2022 expert report. However, as in R v Hart, 2023 BCSC 933, the Crown neither objected to the report being before the court, nor evidently sought to cross-examine on it. In my view the report, though only part of the record before the court, is entitled to significant weight: it is the result of a series of psychometric tests including a Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI), SPECTRA indices of psychopathology, and a Hypersexual Behavior Inventory (HBI); the expert reviewed a lengthy Agreed Statement of Facts, interviewed the offender and reviewed his medical history; response bias profiles were valid; the offender’s responses on the HBI were “well below the clinical cutoff for hypersexuality”; the expert notes “base rate information” for certain male sexual offenders of recidivism of nine per cent over five years and 13 per cent over 10 years; that said, nowhere in his report does the expert apply these rates to AL; rather, he concludes that AL’s test outcomes “suggest a level of risk that is considerably lower” than those base rates; AL was in no need of specific sexual offender treatment going forward.

[44] Based on these test outcomes and his consideration of the record before him – including for example the offender’s remorse and victim empathy – the expert expressed what I find to be a highly relevant and persuasive opinion that AL was a low risk to reoffend and posed no undue risk of harm.

Conclusion

[45] The record in AL’s application, together with the prevailing authorities, support the conclusion that AL is an offender who is “at no increased risk of reoffending”, as understood in Ndhlovu. As such, SOIRA registration would bear no connection to the regime’s purpose of capturing information about him that may assist police prevent and investigate sex offences. Granting AL a s 24(1) remedy would not undermine the purpose of suspending the declaration of invalidity, which was to ensure that those at high-risk of re-offending would be ordered to register as sex offenders.

Our lawyers have been litigating criminal trials and appeals for over 16 years in courtrooms throughout Canada. We can be of assistance to your practice. Whether you are looking for an appeal referral or some help with a complex written argument, our firm may be able to help. Our firm provides the following services available to other lawyers for referrals or contract work:

- Criminal Appeals

- Complex Criminal Litigation

- Ghostwriting Criminal Legal Briefs

Please review the rest of the website to see if our services are right for you.