This week’s top three summaries: R v Shevalev, 2019 BCCA 296, R v Moyles, 2019 SKCA 72, and R v Willis, 2019 NSCA 64.

R v Shevalev (BCCA)

[Aug 14/19] General Concepts of Criminal Law - Co-existence of Mens Rea & Actus Reus - Extension in Murder to Acts to Conceal - 2019 BCCA 296 [Reasons by Frankel J.A. with Tysoe J.A., and Harris J.A. Concurring]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: It is rare for most cases to give as deep a treatment as is delivered here to the necessity of proof by the Crown that there be concurrence between a criminal act and the requisite criminal mental intent. The factual matrix of most cases makes that conclusion obvious, but here the Trial Judge left open the possibility that the accused could be convicted on the basis of a mental intent present only after the application of force leading to death in a murder case. Ultimately, this mistake led to a new trial. Justice Frankel provides a thorough overview of the leading authorities on the concurrence of the act and mental intent a criminal case. Expect to see this case come up in law school texts.

Pertinent Facts

"Vladimir was 80 years old when he died. He lived in a condominium in Vancouver. Alexander was 19 years old. Alexander and his parents emigrated from Russia in 1998. The parents later separated and divorced. At the time of the events in issue, Alexander was living with his mother, Larisa Zemtsova. Prior to this, he had been living with Vladimir. However, Vladimir had kicked Alexander out for stealing money from him." (Para 4)

"Alexander had access to Vladimir's bank account. In late February of 2015, shortly after Alexander obtained his driver's licence, he e-transferred $105,400 from Vladimir's account to his own. On February 25, 2015, Alexander used $92,000 of that money to purchase a used Ferrari. In his evidence, Alexander stated he took the money because when he was 13 years old Vladimir promised to buy him a Porsche when he turned 16 and got his driver's licence. He saw the Ferrari when he went looking to buy an exotic car." (Para 5)

"Vladimir was upset when he found out what Alexander had done and wanted the Ferrari returned. On February 28, 2015, Vladimir and Alexander went to the dealership, but it was closed. The Ferrari was then parked in the parkade of Vladimir's condominium building. Alexander refused to give Vladimir the keys or ownership papers." (Para 6)

"Mr. Sami [a witness] testified Alexander told him Vladimir was taking the Ferrari away and was calling a lawyer. He said that after a few minutes, Alexander picked an item up from the kitchen — possibly a frying pan — and went to the bedroom. He heard two loud "clangs" and screams coming from the bedroom. When he rushed towards the bedroom he saw Alexander and Vladimir in the walk-in closet. Alexander was behind Vladimir with one arm around Vladimir's neck; he was "choking out" Vladimir. Vladimir was gasping for breath; his face and lips were turning purple. On seeing Mr. Sami, Alexander released Vladimir who slumped to the floor. Alexander then asked Mr. Sami to help him place Vladimir on the bed, which he did. Mr. Sami was unable to say whether Vladimir was breathing when placed on the bed. Mr. Sami then left." (Para 9)

"According to Alexander, Vladimir walked toward the bedroom and shortly thereafter shouted in Russian for Alexander to join him. Alexander went into the bedroom, where Vladimir was standing in the walk-in closet. When Alexander went into the closet, Vladimir grabbed him by the front of his sweater and yelled at him in Russian. He told Alexander he was going to take the Ferrari away and make Alexander pay him $100,000." (Para 13)

"Alexander testified Vladimir spat in his face and kneed him in the groin, causing him to feel extreme pain and to fall to the floor. As he was falling, he grabbed Vladimir and took him to the floor, where they struggled. He said that to prevent Vladimir from attacking him further, he held Vladimir from behind, with his arms around Vladimir's upper chest and possibly his neck. It was possible his arms may have "slid up" around Vladimir's throat. He let go when Vladimir stopped struggling. Vladimir slouched on the floor. He first thought Vladimir was pretending to have fainted. However, when he shook Vladimir and did not get a response, he believed Vladimir had fainted. He asked Mr. Sami to help place Vladimir on the bed to make Vladimir more comfortable." (Para 14)

"Alexander said he used a blood pressure monitor in the condominium on Vladimir as he "want[ed] to check that he was going to be okay." He tried twice, but got error messages both times. As Vladimir was breathing, Alexander believed he would wake up. He did not want to wait for Vladimir to wake up, as he was afraid Vladimir would be extremely angry. He went back to the closet to get the keys and documents. He left the condominium at approximately 8:16 p.m., taking with him Vladimir's keys to the condominium, which he used to lock the door. A member of the condominium's concierge team found Vladimir dead on the bed shortly after 10:30 p.m." (Para 15)

"The forensic pathologist called by the Crown testified Vladimir died as a result of substantial external pressure to his neck. She described the injuries to his neck as being "circumferential", meaning they involved the back, front, and both sides of the neck. She was unable to determine the specific mechanism of death; it was either asphyxia — a blockage of the blood vessels and/or airways preventing the body from using oxygen — or because pressure on the neck triggered a fatal cardiac arrhythmia. The latter mechanism was a possibility because Vladimir had a history of heart disease." (Para 16)

The Jury Instruction

"On the second day of its deliberations the jury asked the following question:

In paragraph 144 "If you are satisfied beyond a reasonable doubt that at some point in time during that continuing conduct Mr. Shevalev either meant to cause ..." does "continuing conduct" refer only to the act of the choke hold or does it include what occurred immediately prior to and immediately following the act?" (Para 33)

"The trial judge answered the question as follows and provided the jury with the answer in writing:

Where death results from a series of wrongful acts that you conclude are part of a single transaction, then the Crown does not have to prove that the requisite intent continued throughout that transaction. Nor does the Crown have to prove the precise time during the transaction that death became a likelihood. If death results from a series of wrongful acts that are part of a single transaction then the Crown must establish that the requisite intent coincided at some point in time during that transaction." (Para 37)

Concurrence between the Mental Intent and the Criminal Act

"The requirement for concurrence between the actus reus and mens rea of an offence is a long-standing one, as evinced by the following statement by Lord Kenyon C.J. in Fowler v. Padget (1798), 7 T.R. 509 at 514, 101 E.R. 1103:

[I]t is a principle of natural justice, and of our law, that actus non facit reum nisi mens sit rea. The intent and the Act must both concur to constitute the crime." (Para 38)

"Following the above statements, Cory J. referred with approval to the conclusion reached in Meli v. The Queen, [1954] 1 W.L.R. 228 (P.C.), as another example of what he described as “a series of acts that might be termed a continuous transaction”: at 158. Meli was an appeal by four persons convicted of murder. They planned to take the victim to a hut where they would kill him and then make it appear his death was an accident. They took the victim to the hut, gave him alcohol, and struck him over the head. Believing they had killed the victim, they rolled his body over a cliff and made the scene look like an accident. Unbeknownst to them, the victim was still alive. He later died of exposure. On appeal, they argued they should not have been convicted of murder because they did not have the requisite mens rea at the time of the act which caused the victim’s death, i.e., leaving what they thought was a dead body exposed to the elements." (Para 48)

"In rejecting the appellants’ argument, Lord Reid said this (at 230):

It appears to their Lordships impossible to divide up what was really one transaction in this way. There is no doubt that the accused set out to do all these acts in order to achieve their plan and as parts of their plan; and it is much to refined a ground of judgment to say that, because they were under a misapprehension at one stage and thought that their guilty purpose had been achieved before in fact it was achieved, therefore they are to escape the penalties of the law. Their Lordships do not think that this is a matter which is susceptible of elaboration. There appears to be no case either in South Africa or England, or for that matter elsewhere, which resembles the present. Their Lordships can find no difference relevant to the present case between the law of South Africa and the law of England, and they are of the opinion that by both laws there could be no separation such as that for which the accused contend, so as to reduce the crime from murder to a lesser crime, merely because the accused were under some misapprehension for a timeduring the completion of their criminal plot." (Para 49)

"Having regard to Lord Halsbury's statement in Quinn v. Leathem, [1901] 1 A.C. 495 at 506 (H.L.), that "a case is only authority for what it actually decides", it could be said, having regard to the facts in Cooper, that Cooper only decided that if at any point during an assaultive act (e.g., choking or multiple blows with a bat) that is causative of death the accused had a murderous intent, then the mens rea for murder will have been established. However, I acknowledge this Court and other courts have accepted Cooper also decided the concurrence principle will be satisfied when, as in Meli, a murderous intent is no longer present when the act which is causative of death occurs because the accused believes they have already achieved that intended objective." (Para 53)

"Meli is an exception to the concurrence principle based on policy considerations. In his book Criminal Law – The General Part, 2nd ed., London, Stevens & Sons, 1961, the late Professor Glanville Williams said this with respect to Meli and a similar American case (at 174):

In these cases the accused intends to kill and does kill; his only mistake is as to the precise moment of death and as to the precise act that affects death. Ordinary ideas of justice and common sense require that such a case shall be treated as murder. If so, it is necessary to make an exception to the general principle, and to hold that although the accused thinks that he is dealing with a corpse, still his act is murder if his mistaken belief that it is a corpse is the result of what he himself has done in pursuance of his murderous intent. If a killing by the first act would have been manslaughter, a later destruction of the supposed corpse should also be manslaughter." (Para 54)

"In Kumar v. R., [2016] NZCA 329, 28 C.R.N.Z. 32, leave to appeal ref’d [2016] NZSC 147, the appellants were convicted of murder. They severely beat a man and then burned what they mistakenly believed was his dead body. In dismissing their appeals, Justice Harrison said this:

[35] Thabo Meli’s authority is beyond question: parties cannot avoid criminal liability simply because they believe mistakenly that they have achieved their objective by one act but in fact achieve it by a later and different act if both acts can be treated as logically successive or connected within the one continuous course of conduct attributable to or motivated by the same murderous intent. Depending upon the circumstances, the two acts are treated as one irrespective of ostensible temporal or physical separation. Thabo Meli represents an extended and principled application of the criminal law’s concurrence requirement. Indeed, in R v Cooper the Supreme Court of Canada affirmed that the authority does not depart from the basic premise that the mental element of a crime must overlap with the unlawful conduct: [footnotes omitted].

[Emphasis added.]" (Para 55)

"In my view, Frizzell is an application of the principle in Meli, that when death is caused by the actions of an accused in disposing of what they mistakenly believe is a dead body, criminal liability will be determined by the mens rea that existed at the time the accused committed the act which led them to believe the victim was dead." (Para 61)

"R. v. Talbot, 2007 ONCA 81 (CanLII), 217 C.C.C. (3d) 415, involved a Crown appeal from acquittal on a charge of second degree murder. Mr. Talbot and the victim got into an altercation outside a restaurant. There was conflicting evidence as to who started the altercation. Mr. Talbot struck the victim in the face with a single punch, causing the victim to fall backwards and hit his head on the pavement. About a minute later, Mr. Talbot kicked the victim. A pathologist testified the cause of death was complications from blunt force head injuries. He further testified it was speculative as to whether the kicks exacerbated the head injuries. Mr. Talbot’s sole defence was self-defence." (Para 63)

"Further, in response to the Crown’s argument that the answer was inadequate because it did not go on to discuss the fact criminal liability can arise during the course of an altercation, even if an accused initially acted in self-defence, Doherty J.A. stated:

[87] There can be no quarrel with these authorities. Nor could anyone take exception with the Crown’s assertion that a person who is initially justified in acting in self defence is not “cloaked in legal immunity” should that person proceed to attack his defenseless assailant. However, if the act that causes death is justified in self defence, the homicide cannot be made culpable by a subsequent unlawful assault no matter how morally reprehensible that assault may be.

[Emphasis added.] (Para 68)

"What Talbot reflects is the principle that, in the context of a single transaction, a subsequent unlawful act accompanied by a murderous intent cannot support a conviction for murder when death was caused by a previous non-culpable act." (Para 69)

Application to the Case

"Returning to the present appeal, the Crown's case was that the chokehold was the unlawful act that caused Vladimir's death. In his closing address to the jury, Crown counsel stated:

[T]he Crown's theory [is] that the deceased was placed on the bed either deceased or in an unconscious state and expired. It's as simple as that.

The Crown did not suggest, nor was there any evidence, that any other act contributed to Vladimir's death." (Para 73)

"The chokehold was the starting and ending point of the actus reus. Accordingly, the jury had to be satisfied Alexander had a murderous intent when he applied that hold. If the jury was not so satisfied, then Alexander was entitled to be acquitted of murder regardless of what happened afterwards." (Para 74)

"By its question, the jury sought guidance with respect to the time-frame within which the mens rea for murder had to exist. The answer given was not correct. Rather than limiting the time-frame to when the chokehold was applied, the answer expanded the time-frame and invited the jury to consider what happened afterwards. However, even if the jury found that Vladimir was alive when he was placed on the bed, nothing that occurred subsequent to the chokehold contributed to his death." (Para 75)

"As it is possible the jury convicted Alexander without being satisfied he had the requisite intent for murder when he applied the chokehold, his conviction cannot stand." (Para 78)

R v Moyles (SKCA)

[July 30/19] Charter s.8 - General Warrant and Failing to Ask to do a Controlled Delivery - 24(2) Resultant Warrantless Search - 2019 SKCA 64 [Reasons by Barrington-Foote J.A. with Jackson J.A., and Ryan-Froslie J.A. concurring]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: In this case, the police had everything they needed to get judicial authorization for a search following a controlled delivery by mail of a controlled substance, but they forgot to explicitly include permission for that in the draft warrant. Interestingly the Affidavit in support indicated an intention for that to occur, but since the signed authorization did not, the delivery was deemed a Charter violation on appeal. The importance of this case is that courts will often read the Affidavit in support of a warrant as almost expanding the warrant itself as they explain the issuing justice would have know the intentions of the police therefrom. This case stands for the proposition that unless something is explicitly authorized in the warrant, it's not authorized.

Pertinent Facts

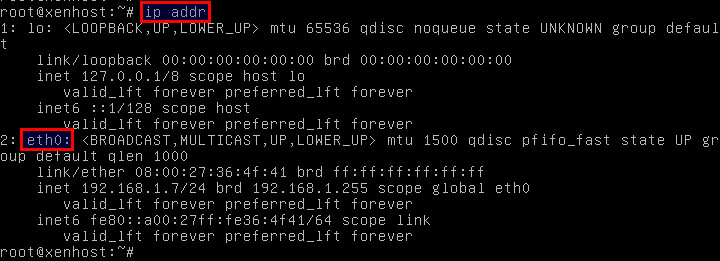

"The investigation which resulted in these charges began with the interception of two boxes at the Vancouver International Airport on August 6, 2014. The boxes, which were shipped from China and addressed to "Bryan" at 383 Petterson Drive, a residence in Estevan, Saskatchewan [house], were labelled as containing peppermint oil. A suspicious Canada Border Services Agency [CBSA] officer opened them and found six plastic bottles containing GBL." (Para 4)

"GBL is listed as a precursor in Schedule VI to the CDSA. Section 6(1) of the CDSA provides that it is an offence to import or export a Schedule VI substance." (Para 5)

"On August 13, 2014, Constable Lon Schwartz, the team leader of the integrated unit, swore two Informations to Obtain warrants [ITO]. Both ITOs said the affiant had reasonable grounds to believe Bryan Moyles had committed or would commit one or more of three offences relating to GBL: importing, pursuant to s. 6(1) of the CDSA; possession for the purpose of trafficking, pursuant to s. 5(2) of the CDSA; and conspiracy to commit those CDSA offences. As noted above, possession of GBL for the purpose of trafficking is not an offence." (Para 8)

"One ITO requested a general warrant pursuant to s. 487.01 of the Criminal Code [general warrant ITO] authorizing the police to conduct the controlled delivery, and to enter and search the house only after a box alarm was triggered. The other ITO requested a s. 11 CDSA warrant [CDSA ITO] authorizing entry, search and seizure." (Para 9)

"Both warrants were issued August 13, 2014, for a seven-day period commencing at 11:00 a.m. on August 13. The general warrant authorized the police to install and monitor the box alarms. It said the police could not enter the residence until there were reasonable grounds to believe Bryan Moyles and/or unknown persons are or have been in actual possession of the boxes. However, it did not refer to the controlled delivery. The CDSA warrant authorized the police to enter the house at the times specified in the ITO. It did not refer to the delivery of the boxes at all." (Para 10)

"The controlled delivery took place on August 14, 2014. An RCMP undercover officer went to the door of the house. A person who identified himself as Bryan Moyles answered the door, showed identification, and signed for the delivery. After a minute or two, the police received notification from one of the box alarms that a package had been opened. They knocked, and receiving no answer, broke open the front door." (Para 11)

"Mr. Moyles, who was coming down the stairs, was arrested. He was taken to a police car five to seven minutes later, after the police had finished clearing the house." (Para 12)

The General Warrant

"The general warrant ITO made it very clear its central purpose was to obtain authorization to carry out the controlled delivery, and that the authority to search the house depended on that delivery being carried out. The controlled delivery is described step by step, twice. The general warrant ITO states that using this investigative technique "would, if not authorized, constitute an unreasonable search or seizure in respect of a person or a person's property". The section titled "Authorization Requested" is as follows:

IT IS REQUESTED THAT a warrant be granted authorizing peace officers to utilize the proposed investigative techniques under the following terms and conditions, which will afford evidence concerning the aforesaid offences:

a) That "the package" be detained, the illicit contents of the package be seized and switched out for a similar substance. "The package" would then be equipped with an intrusion alarm or similar device. "The package" will be delivered by a peace officer posing as a courier. Once the package is opened and the alarm activated, peace officer will gain access to "the location" to seek further evidence to "the offences"." (Para 34)

"The general warrant itself, on the other hand, does not contain this or similar language. It authorized the police to install and maintain box alarms. It says entry into and a search of the "the location" where "the package" is delivered to is not authorized until there were reasonable grounds to believe Mr. Moyles and/or unknown persons are or have been in possession of the package. It refers to the possibility the alarm may be activated. However, it does not refer to the delivery of the package by a peace officer at all." (Para 35)

"The Crown did not argue that the general warrant implicitly authorized the controlled delivery. That was an appropriate concession. I would not have been prepared to read it that generously. The general warrant did not authorize the controlled delivery, and was for that reason invalid." (Para 36)

Analysis of Charter Section 8

"With respect, the Crown's position invites the Court to ignore the substance of what occurred. The police officer was not a courier delivering the boxes that arrived at the Vancouver International Airport. He delivered a package the police created, which included a monitoring device. That package was an investigatory tool, and the purpose of delivering that investigatory tool was to enable the police to secure evidence against Mr. Moyles or another occupant of the house. That was their purpose and their purpose is the issue." (Para 52)

"The Crown bears the burden of demonstrating a warrantless search is authorized by a reasonable law and carried out in a reasonable manner: R v Mann, 2004 SCC 52 (CanLII) at para 36, [2004] 3 SCR 59. In this case, that reasonable law was the implied licence to knock, which did not apply. That being so, the controlled delivery was an unreasonable search which breached Mr. Moyles’s s. 8 Charter right to be secure against unreasonable search or seizure." (Para 54)

Section 24(2) Analysis

Seriousness of the Violation

"As to the breach of Mr. Moyles's s. 8 Charter rights, the general warrant ITO demonstrates that Constable Schwartz was well aware the police needed a warrant to conduct the controlled delivery. As such, the failure to include a provision authorizing the controlled delivery in the general warrant was negligent. As a result of that omission, the controlled delivery — that is, the delivery of the boxes containing the alarms — was a warrantless and illegal search of Mr. Moyles's residence." (Para 85)

"In the result, the Charter-infringing conduct of the state was sufficiently serious in relation to each of the s. 8 and s. 10(b) [unnecessary delay in access to counsel call] breaches to strongly favour the exclusion of evidence obtained in a manner that infringed Mr. Moyles's Charter rights. The issue as to what evidence was obtained in that manner is discussed below." (Para 87)

Seriousness of the Impact on the Accused

"For the reasons noted in my analysis above of the trial judge’s approach to this issue, it is my view the delay in implementing Mr. Moyles’s s. 10(b) right seriously impacted the interests protected by the right. To reiterate, immediate access to counsel is central to the interests protected by the right to counsel. Here, the delay was lengthy. It was found by the trial judge to be very stressful for Mr. Moyles, a fact that speaks to the impact on his loss of a lifeline and to the risk that he might involuntarily make admissions against interest. The impact of this breach was not fleeting or technical (Grant at para 76)." (Para 89)

"The impact of the s. 8 breach was also at the serious end of the scale. The controlled delivery was to Mr. Moyles’s house, where he enjoyed the highest expectation of privacy. Circumstances which denote a high expectation of privacy favour the exclusion of evidence (Paterson at para 49), and “[a]n illegal search of a house will therefore be seen as more serious at this stage of the analysis” (Grant at para 113). The controlled delivery resulted in Mr. Moyles identifying himself and signing the delivery slip. It also resulted in the placement of box alarms which served as a monitoring device in the house. Further, the signal sent by the box alarm led directly to the forced entry." (Para 90)

What evidence was obtained in a manner that violated Charter Rights?

"In this case, it is clear the warned statement had a sufficient temporal and contextual connection to be evidence “obtained in a manner”. The same is true of the evidence obtained in the course of the controlled delivery. That evidence included the fact Mr. Moyles identified himself and signed the delivery slip, took delivery of the boxes, and that a box alarm was triggered shortly thereafter. There is an insufficient connection to the evidence relating to the interception of boxes at the Vancouver airport. The more difficult question is whether the remaining evidence gathered at the residence, and particularly the boxes, is evidence obtained in a manner that breached the Charter, despite the fact that search was not warrantless or illegal." (Para 98)

"It is my view that evidence of the items seized in the house is evidence obtained in a manner which infringed the Charter. The decision in R v Boutros, 2018 ONCA 375 (CanLII), 361 CCC (3d) 240 [Boutros], is instructive. In that case, there were s. 8 and s. 10(b) Charter breaches. The evidence at issue was text messages which were finally seized pursuant to a production order. The trial judge found that he need not conduct a s. 24(2) analysis, as there was no Charter breach relating to the production order." (Para 99)

"The appellant contended that there was a sufficient temporal, contextual, or causal connection to call for exclusion under s. 24(2). Justice Doherty agreed that a s. 24(2) analysis was necessary, as “evidence obtained pursuant to a lawful production order, or search warrant, may still be obtained ‘in a manner’ that infringed a Charter right” (Boutros at para 19). He relied on R v Grant, 1993 CanLII 68 (SCC), [1993] 3 SCR 223, in support of that proposition, commenting as follows: ...

In keeping with Grant, and other authorities, e.g. R. v. Plant, 1993 CanLII 70 (SCC), [1993] 3 S.C.R. 281, at p. 296; R. v. Côté, 2011 SCC 46 (CanLII), [2011] 3 S.C.R. 215, at paras. 78-79, the trial judge should have determined whether any of the Charter breaches that occurred before the police obtained the text messages under the authority of the lawful production order were integral to the investigative process that ultimately led to the acquisition of the text messages by the police. (Para 100)

"Cast in those terms, I conclude that the s. 8 Charter breach was integral to the investigative process that led to the seizure of the boxes and other items in the house. That, too, is evidence obtained in a manner that infringed Mr. Moyles’s s. 8 Charter rights. (Para 101)

Balancing

"In this case, the first and second inquiries, taken together, make out a strong case for exclusion. The warrantless controlled delivery to Mr. Moyles’s residence – which was a central element of the investigative process – was serious state misconduct with a serious impact on Mr. Moyles’s Charter-protected interests. So too was the s. 10(b) breach, which, in the period after the house was secured, might fairly be described as demonstrating either a fundamental misunderstanding of or a cavalier disregard for Mr. Moyles’s rights. To echo the comments of Doherty J.A. in McGuffie, “[t]he court can only adequately disassociate the justice system from the police misconduct and reinforce the community’s commitment to individual rights protected by the Charter by excluding the evidence” (at para 83)." (Para 105)

R v Willis (NSCA)

[July 31/19] – Improper Use of Prior Consistent Statements - Brown v. Dunn and Trivial Inconsistencies - Unbalanced Scrutiny of Defence Evidence – 2019 NSCA 64 [Reasons by Michael J. Wood C.J.N.S., with Beveridge J.A., and Farrar J.A. concurring]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: This case provides a good overview of case law governing improper use of prior consistency of a complainant. Also, the trial judge used trivial inconsistencies to ground a Brown v Dunn decision to give less weight to the evidence of the accused. Together, these errors and others demonstrated the uneven treatment of the evidence of the complainant and the accused.

Pertinent Facts

"In February 2016, the appellant, Carie Willis, was charged with three offences arising out of events which were alleged to have occurred between June and December 2003 when he was employed with the Halifax Enforcement Unit of Citizenship and Immigration Canada. In late 2003, the Enforcement Unit became part of the Canada Border Services Agency. The charges were for sexual assault contrary to s. 271 of the Criminal Code, R.S.C. 1985, c.C-46, extortion contrary to s. 346(1.1)(b) of the Code and breach of trust contrary to s. 122 of the Code." (Para 1)

"The complainant, A.A., arrived in Canada in 1996 as a student. Her authorization to remain in Canada expired in 2001 following which she made an application for refugee status which was turned down in early 2003. A deportation order was issued with respect to A.A. in April 2003, and Mr. Willis was given responsibility for implementing her removal from Canada. Arrangements were made for A.A. to fly out of Halifax in June 2003; however, she did not show up for her flight. She has remained in Canada since that time and obtained permanent resident status in 2014." (Para 2)

"The charges against Mr. Willis arose out of allegations by A.A. that he induced her to enter into a non-consensual sexual relationship in exchange for which he would make sure that deportation proceedings were not taken against her." (Para 3)

"The testimony of A.A. and Mr. Willis cannot be reconciled. A.A. says that shortly after being advised by Mr. Willis of the particulars of her deportation he coerced her into a sexual relationship in exchange for turning a blind eye. According to her, this lasted from June 2003 until December of that year. During the last month they had intercourse several times a week. Mr. Willis says that after telling A.A. of the deportation arrangements she missed her flight and he never saw her again until the preliminary inquiry in relation to these charges, which took place in 2017." (Para 12)

Prior Consistent Statements

"Improper reliance on prior consistent statements is an error of law which is reviewable on a standard of correctness (R. v. Laing, 2017 NSCA 69 (CanLII) at paras. 85-86; R. v. T(P), 2014 NLCA 6 (CanLII) at para. 12)." (Para 8)

"Where a prior statement is admissible to rebut an allegation of recent fabrication, it can only be used for that limited purpose. The statement is not admissible to prove the truth of its contents. To hold otherwise would suggest that repetition makes a story more credible which is a proposition that has been repeatedly rejected." (Para 16)

"The Supreme Court of Canada discussed the use which can be made of prior statements when admitted to rebut allegations of recent fabrication in R. v. Stirling, 2008 SCC 10 (CanLII). In that case Justice Bastarache, writing for the Court, said: ...

7 However, a prior consistent statement that is admitted to rebut the suggestion of recent fabrication continues to lack any probative value beyond showing that the witness’s story did not change as a result of a new motive to fabricate. Importantly, it is impermissible to assume that because a witness has made the same statement in the past, he or she is more likely to be telling the truth, and any admitted prior consistent statements should not be assessed for the truth of their contents. As was noted in R. v. Divitaris (2004), 2004 CanLII 9212 (ON CA), 188 C.C.C. (3d) 390 (Ont. C.A.), at para. 28, “a concocted statement, repeated on more than one occasion, remains concocted”; see also J. Sopinka, S. N. Lederman and A. W. Bryant, The Law of Evidence in Canada (2nd ed. 1999), at p. 313. This case illustrates the importance of this point. The fact that Mr. Harding reported that the appellant was driving on the night of the crash before he launched the civil suit or had charges against him dropped does not in any way confirm that that evidence is not fabricated. All it tells us is that it wasn’t fabricated as a result of the civil suit or the dropping of the criminal charges. There thus remains the very real possibility that the evidence was fabricated immediately after the accident when, as the trial judge found, “any reasonable person would recognize there was huge liability facing the driver” (Ruling on voir dire, June 21, 2005, at para. 24). The reality is that even when Mr. Harding made his very first comments about who was driving when the accident occurred, he already had a visible motive to fabricate — to avoid the clear consequences which faced the driver of the vehicle — and this potential motive is not in any way rebutted by the consistency of his story. It was therefore necessary for the trial judge to avoid using Mr. Harding’s prior statements for the truth of their contents." (Para 17)

Application

"In this case, the trial judge admitted, and considered, prior statements made by A.A. concerning the alleged sexual relationship with Mr. Willis. In her decision, these statements, and the use made of them, were described as follows:

22 She discussed the sexual relationship with her brother within a few months after December 2003 and with her sister sometime early in 2004. She said R.D. knew, as well, but she did not recall telling him and believed F.A., her brother, had told him about it.

...

29 There were other witnesses for the Crown: Katie Tinker, to whom I have just referred, and she said it would be unusual to live without status for years. She said A.A. disclosed the sexual relationship to her when they met in 2014. She said she believed the Humanitarian and Compassionate application claim would be strong even without it. Then, after they had the interview with the Canadian Border Services Agency people, A.A. changed her mind about disclosing it because they had told her they were going to go ahead with deportation, in any event. ...

74 For these reasons, I do not believe Mr. Willis' testimony, nor does his testimony raise a reasonable doubt. I accept the evidence of A.A. and of Mr. Lawrence, and there is confirmation of portions of her story in the testimony of her brother, F.A., and R.D. with respect to the move to C. Street. As well, A.A. told her brother and her sister, V.A., and Katie Tinker and Sgt. McNeil of the sexual relationship." (Para 19)

"The decision does not refer to admitting any prior statements to rebut recent fabrication. It was not clear when the alleged fabrication was said to arise, since the defence position was that A.A. had lied about the allegations from the very beginning. The Crown confirmed that it was not seeking to admit the statements for the truth of their contents." (Para 20)

"Over the objections of defence counsel, the trial judge admitted the statements to A.A.'s brother, her sister, and Ms. Tinker to rebut allegations of recent fabrication. There never was any evidence of what A.A. said to her sister beyond those passages noted above. In other words, the alleged prior statement to her was never proven." (Para 22)

"Even if the complainant's previous statements were admissible for the purposes described by the trial judge, they could never be used to corroborate her trial evidence because they were not admissible for their truth. In para. 74 of her decision, the trial judge indicates this is precisely what she did with the statements made by A.A. to those individuals. This use for an improper purpose is an error of law which undermines a fundamental part of the trial judge's reasoning, her assessment of the credibility of A.A." (Para 24)

"I would allow this ground of appeal." (Para 25)

The Rule in Brown v Dunn

"See also the decision of this Court in R. v. Mauger, 2018 NSCA 41 (CanLII) (at para. 47) where Beveridge J.A. held that the decision on whether the rule is engaged must be correct." (Para 10)

"This rule arises out of the House of Lords decision in Browne v. Dunn and is fundamentally a question of trial fairness. The basic premise is that if defence counsel intends to lead evidence to contradict a Crown witness on a material point, they should put to that witness the potential contradictory evidence and give them an opportunity to provide any explanation they may have. Justice Watt of the Ontario Court of Appeal described the underlying considerations in R. v. Quansah, 2015 ONCA 237 (CanLII):

76 The rule in Browne v. Dunn, as it has come to be known, reflects a confrontation principle in the context of cross-examination of a witness for a party opposed in interest on disputed factual issues. In some jurisdictions, for example in Australia, practitioners describe it as a “puttage” rule because it requires a cross-examiner to “put” to the opposing witness in cross-examination the substance of contradictory evidence to be adduced through the cross-examiner’s own witness or witnesses.

77 The rule is rooted in the following considerations of fairness:

i. Fairness to the witness whose credibility is attacked:

The witness is alerted that the cross-examiner intends to impeach his or her evidence and given a chance to explain why the contradictory evidence, or any inferences to be drawn from it, should not be accepted: R. v. Dexter, [2013] O.J. No. 5686, 2013 ONCA 744 (CanLII), 313 O.A.C. 226, at para. 17; Browne v. Dunn, at pp. 70-71.

ii. Fairness to the party whose witness is impeached:

The party calling the witness has notice of the precise aspects of that witness’s testimony that are being contested so that the party can decide whether or what confirmatory evidence to call; and

iii. Fairness to the trier of fact:

Without the rule, the trier of fact would be deprived of information that might show the credibility impeachment to be unfounded and thus compromise the accuracy of the verdict.

78 In addition to considerations of fairness, to afford the witness the opportunity to respond during cross-examination ensures the orderly presentation of evidence, avoids scheduling problems associated with re-attendance and lessens the risk that the trier of fact, especially a jury, may assign greater emphasis to evidence adduced later in trial proceedings than is or may be warranted." (Para 26)

"The rule is only triggered when the potential contradiction relates to a matter of substance. The Court in Quansah described this requirement in the following terms:

81 Compliance with the rule in Browne v. Dunn does not require that every scrap of evidence on which a party desires to contradict the witness for the opposite party be put to that witness in cross-examination. The cross-examination should confront the witness with matters of substance on which the party seeks to impeach the witness’s credibility and on which the witness has not had an opportunity of giving an explanation because there has been no suggestion whatever that the witness’s story is not accepted: Giroux, at para. 46; McNeill, at para. 45. It is only the nature of the proposed contradictory evidence and its significant aspects that need to be put to the witness: Dexter, at para. 18; R. v. Verney 1993 CanLII 14688 (ON CA), [1993] O.J. No. 2632, 87 C.C.C. (3d) 363 (C.A.), at pp. 375-376; Paris, at para. 22; and Browne v. Dunn, at pp. 70-71." (Para 27)

Application

"Although she does not expressly say so, I infer that the only reason for the trial judge giving reduced weight to Mr. Willis' evidence, as a result of a failure to cross-examine Mr. Lawrence, was her belief that the rule in Browne v. Dunn applied. In my view, she was wrong; the rule was not engaged because there was no contradiction between the evidence of Mr. Willis and Mr. Lawrence on a point of substance. The issues were peripheral, at best, and there is nothing to suggest that Mr. Lawrence had any knowledge about Mr. Willis' use of notebooks, overtime practices, or training." (Para 36)

"By incorrectly identifying these as Browne v. Dunn violations, the trial judge reduced the weight of Mr. Willis' testimony on these points which ultimately diminished his credibility in her eyes." (Para 37)

"The application of the rule in Browne v. Dunn, when it was not engaged, is an error of law which adversely affected the trial judge's assessment of Mr. Willis' evidence." (Para 38)

"I would also allow this ground of appeal." (Para 39)

Uneven Scrutiny

"It is an error of law to apply differential scrutiny to the evidence of the defence and Crown, and errors of law are reviewed on a standard of correctness (R. v. Dim, 2017 NSCA 80 (CanLII) at para. 48)." (Para 11)

"This ground of appeal is generally difficult to make out. The Ontario Court of Appeal described the standard to be met in R. v. Kiss, 2018 ONCA 184 (CanLII) as follows:

83 This is a notoriously difficult ground of appeal to succeed upon because a trial judge’s credibility determinations are entitled to a high degree of deference, and courts are justifiably skeptical of what may be veiled attempts to have an appellate court re-evaluate credibility: R. v. D.T., 2014 ONCA 44 (CanLII), at paras. 71-73; and R. v. Aird, 2013 ONCA 447 (CanLII), at para. 39. An “uneven scrutiny” ground of appeal is made out only if it is clear that the trial judge has applied different standards in assessing the competing evidence: Howe, at para. 59. Where the imbalance is significant enough, “the deference normally owed to the trial judge’s credibility assessment is generally displaced”: R. v. Rhayel, 2015 ONCA 377 (CanLII), at para. 96; R. v. Gravesande, 2015 ONCA 774 (CanLII), 128 O.R. (3d) 111, at para. 19; and R. v. Phan, 2013 ONCA 787 (CanLII), at para. 34." (Para 40)

"By way of illustration, the Court gave examples of what it considered inconsistent treatment between the Crown and defence in the following passage:

90 Third, the trial judge treated the contradiction over who was awake when Mr. Kiss arrived home as a significant contradiction, even though it was a collateral point. He also placed "significant" reliance on Mr. Kiss's inconsistent accounts of his sobriety, another collateral point. This included inconsistencies in Mr. Kiss's evidence about the alcohol he consumed. The problem is that the trial judge did not treat the collateral inconsistencies in K.S.'s testimony the same way." (Para 42)

"Indeed, the use which the trial judge makes of minor or collateral inconsistencies or contradictions appears to be a theme in some successful appeals based upon uneven scrutiny. When those issues are used to undermine the credibility of the defence evidence, but ignored or diminished in relation to the Crown evidence, a successful appeal may result as happened in Kiss. This was also the case in R. v. Gravesande, 2015 ONCA 774 (CanLII) where the Court said:

42 When read as a whole, the trial judge’s reasons demonstrate a degree of scrutiny of the prosecution evidence that was tolerant and relaxed as compared to the irrelevant, tenuous and speculative observations largely about collateral matters applied to unfairly discount the appellant’s evidence." (Para 43)

"Uneven scrutiny may also be found when there is no critical assessment of inconsistencies which could undermine the Crown evidence. R. v. D.D.S., 2006 NSCA 34 (CanLII) was such a case. In that decision Saunders J.A. described the approach to be taken as follows:

51 The judge was obliged to look at all of the evidence not simply to see if there was other evidence which supported and enhanced that of the complainant, but also to determine if there were evidence that contradicted or tended to contradict that of the complainant; and more importantly, whether that evidence, or lack thereof, created a reasonable doubt." (Para 44)

Application

"In this case, both A.A. and Mr. Willis testified and the assessment of their evidence was crucial to the trial judge's decision. A.A. said that there was a sexual relationship which spanned several months, and Mr. Willis testified that there was limited interaction between them and only in relation to his work in the Halifax Enforcement Unit of Citizenship and Immigration of Canada. A.A. testified that all of the sexual activity took place in her home and nobody else was present. There were no witnesses that saw them together, nor any physical evidence such as photographs, emails, text messages, etc. In a case such as this, the importance of a balanced assessment of the witness' testimony is obvious." (Para 46)

"In my view, the errors made by the trial judge in relation to the first two grounds of appeal tilted the balance in favour of the Crown and against Mr. Willis. The trial judge buttressed the credibility of A.A. by improperly using prior consistent statements to corroborate her evidence. She then undermined Mr. Willis' credibility by incorrectly applying the rule in Browne v. Dunn." (Para 47)

"There are other examples of this unequal treatment. As was the case in Kiss and Gravesande, the judge relied on what could only be described as collateral or minor inconsistencies to assist in her conclusion that Mr. Willis was not credible." (Para 48)

"Both A.A. and Mr. Willis testified that they had a meeting at Tim Hortons to discuss her file. Mr. Willis said that he drove his own car to the meeting since he intended to carry on and pick up his daughter at Mount Saint Vincent University and then go home. Mr. Willis' co-worker, Mr. Lawrence, said that they would not use their personal vehicles for work without authorization from their manager. In cross-examination, Mr. Willis said that he had the manager's authorization. The trial judge's decision comments on this evidence as follows:

67 He also said he drove his own vehicle to the meeting at Tim Hortons, whereas Mr. Lawrence said they did not use their own vehicles for work." (Para 49)

"Mr. Willis testified that he did not know where A.A. was employed when he was dealing with her in June 2003. Whether he knew or not was irrelevant to the Crown's case. However, Mr. Lawrence testified that he would usually ask a client for this information. The trial judge found this to be a contradiction that formed part of her justification for not believing Mr. Willis. In her decision she said:

71 Mr. Willis testified he did not know where A.A. worked, but Mr. Lawrence said it was usual to ask this. Furthermore, A.A. said he knew, because he said he would not go there for two weeks after her failure to show at the airport. Mr. Willis said he did not contact her brother or her coworkers because he did not know of F.A. or where A.A. worked." (Para 53)

"The trial judge does not appear to have subjected A.A.'s evidence to the same degree of scrutiny as she did for Mr. Willis. There are a number of examples that illustrate this point." (Para 55)

"A.A. admitted lying on several previous occasions, including to her parents with respect to whether she was continuing her university studies and in her application for refugee status. She also omitted any reference to the alleged sexual relationship with Mr. Willis in her initial application for permanent residence status in 2014. The trial judge discounted this evidence:

44 She admitted lying on her refugee claim and misleading her parents, but I do not consider this to affect her credibility in court. It could have, except for the nature of her testimony. As I said, she gave details, was not shaken on cross-examination, and knew things she could not have known without Mr. Willis being with her and without him telling her about, for example, the change in her flight. Nor do I believe, as the Defence suggests, that she made all this up to get to stay in Canada. She only learned of the Humanitarian and Compassionate application in 2014 and had told her brother and her sister of these incidents many years before." (Para 56)

"If the evidence of Mr. Willis and his wife, about circumcision, was accepted, it could seriously undermine A.A.'s version of events. It might well raise a reasonable doubt with respect to Mr. Willis' guilt. The trial judge did not mention this contradiction in her decision. She sets out the testimony of A.A. on the issue but not the evidence of Mr. Willis or his wife. We do not know why. Mr. Willis' evidence is criticized on immaterial and sometimes non-existent contradictions whereas this evidence, which potentially goes to the heart of the complainant's credibility and reliability, is not referred to." (Para 61)

Conclusion

"I would allow the appeal and remit the matter for a new trial. The amended Notice of Appeal requests a trial by judge and jury. Mr. Willis shall be released on the same bail conditions which were applicable prior to his trial with the exception that his residence is now in Montreal." (Para 64)