This week’s top three summaries: R v Verrilli, 2020 NSCA 64: #unsealing ITO, R v Kapustinsky, 2020 ABQB 611: #sexual history and R v Savage, 2020 ABQB 618: s.8 and pre-test #observation period

R v Verrilli, 2020 NSCA 64

[October 15, 2020] Open Court Principle and Unsealing Search Warrant ITOs [Reasons by Chief Justice Michael J. Wood with Beveridge and Beaton JJ.A. concurring]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: On occasion a defendant wants to know why police targeted them for a search even though charges are withdrawn prior to such disclosure. For example, when they want compensation for the violation of their Charter rights afterwards or when they want to fight continued state efforts to seize their property under civil forfeiture laws. This case provides a roadmap and a useful distinguishing of such documents for affidavits in support of wiretap authorisations (which involve a different test for subsequent access). The composition of the panel will be particularly persuasive when this case is used outside Nova Scotia.

Overview

[1] In March 2018, Daniel Verrilli was under investigation for allegedly possessing cocaine for the purposes of trafficking. Police obtained three search warrants authorized by justices of the peace which were used to conduct searches of his home, business and motor vehicles. No charges were laid against Mr. Verrilli and various items which had been seized during the searches were returned to him.

[2] Mr. Verrilli wanted to determine why he had been the subject of the searches and made application to the Provincial Court of Nova Scotia for access to the documents provided to the justices of the peace to support the search warrant requests. These are generally referred to as Informations to Obtain (the “ITOs”). These had been sealed by order of the authorities who issued the warrants.

The Issue

[15] The parties agree the issue on appeal is:

What is the test to be applied in determining a non-accused person’s application under s. 487.3(4) of the Criminal Code to access information subject to a valid sealing order after a search warrant has been executed?

Analysis

[19] The submissions of the parties invite a comparative analysis of s. 187 and s. 487.3 of the Criminal Code....

[20] Both sections describe a process whereby applications and supporting materials for investigative tools may be kept secret. They also outline the procedure for requesting access to these materials, particularly by accused persons. However, there is an obvious and significant difference. Under s. 187, a wiretap ITO is automatically confidential and placed under seal. With a search warrant ITO, under s. 487.3, there is no legislated confidentiality or sealing but rather an application may be made for a discretionary sealing order. Subsection 4 adds the procedure for a subsequent application to terminate or vary any of the terms and conditions of the order. There is no authority in s. 187 to vary or terminate the statutory confidentiality; although, an application can be made to a judge (under ss. 1.3) for an order to copy and examine the documents.

[21] The fact that Parliament chose to deal with the secrecy of the ITOs in relation to these two investigative tools so differently explains the variance in the jurisprudence related to these two sections of the Code.

[22] I will start my analysis by discussing the open court principle as described in Dagenais/Mentuck followed by an examination of search warrants and s. 487.3 and, finally, consideration of s. 187 and the decision in Michaud.

Search Warrants - s.487.3

21 After a search warrant has been executed, openness was to be presumptively favoured. The party seeking to deny public access thereafter was bound to prove that disclosure would subvert the ends of justice.

22 These principles, as they apply in the criminal investigative context, were subsequently adopted by Parliament and codified in s. 487.3 of the Criminal Code, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-46. That provision does not govern this case, since our concern here is with warrants issued under the Provincial Offences Act of Ontario, R.S.O. 1990, c. P.33. It nonetheless provides a useful reference point since it encapsulates in statutory form the common law that governs, in the absence of valid legislation to the contrary, throughout Canada.

23 Section 487.3(2) is of particular relevance to this case. It contemplates a sealing order on the ground that the ends of justice would be subverted, in that disclosure of the information would compromise the nature and extent of an ongoing investigation. That is what the Crown argued here. It is doubtless a proper ground for a sealing order with respect to an information used to obtain a provincial warrant and not only to informations under the Criminal Code. In either case, however, the ground must not just be asserted in the abstract; it must be supported by particularized grounds related to the investigation that is said to be imperilled. And that, as we shall see, is what Doherty J.A. found to be lacking here.

[30] As set out in Toronto Star, the Dagenais/Mentuck test applies at every stage of a judicial proceeding and to all discretionary orders that have the effect of limiting the open court principle. The test has been applied on applications to terminate or vary sealing orders under s. 487.3(4) of the Code (Ottawa Citizen Group Inc. v. R., (2005) 2005 CanLII 38578 (ON CA), 75 O.R. (3d) 590 (CA); R. v. Vice Media Canada Inc., 2017 ONCA 231).

[31] In R. v. Esseghaier, 2013 ONSC 5779, Durno, J. considered an application under s. 487.3(4) to unseal ITOs in relation to search warrants. An issue was raised with respect to who bore the burden on the application. In applying Dagenais/Mentuck, he concluded that the onus was on the Crown and accused, both of whom wanted the sealing order to continue. His analysis was as follows:

43 First, the sealing order was obtained in an ex parte application in chambers at a time when there was a presumption that the ITO would not be public because of the ongoing investigation. That presumption no longer applies after the warrants were executed. The context in which the determination is made has changed. The presumption of sealing no longer applies. Toronto Star, 2005, at para. 23. In Canadian Broadcasting Corp. v. New Brunswick (Attorney General), 1996 CanLII 184 (SCC), [1996] 3 S.C.R. 480 (S.C.C.), at para. 71, LaForest J. held that "[t]he burden of displacing the general rule of openness lies on the party making the application." I am not persuaded the reference in New Brunswick to the party making the application relates to an application to unseal because it refers to displacing the general rule.

44 Second, to put the onus on the media would be to reverse the presumption in Dagenais-Mentuck. The effect would be that if a judge was persuaded to seal the ITO during the investigative stage, the presumption of openness would be reversed when the investigation was completed.45 Third, Michaud, relied upon by Jaser, was a case involving a presumption of secrecy, not one of openness. That Michaud was unsuccessful in overcoming the presumption of secrecy does not assist Mr. Jaser.

[33] It is clear from all these authorities, once a warrant has been executed, there is a presumption that the ITO will become accessible to the public unless the party wishing to limit that access can justify the limitations being sought. This applies not just at the initial application for a search warrant where a sealing order may be requested, but also any subsequent application to vary or terminate that order under s. 487.3(4).

Conclusion

[36] For an application under s. 487.3(4) of the Code following execution of a search warrant, the Dagenais/Mentuck principles apply and any party seeking to continue a sealing order limiting access to the supporting ITO bears the burden of justification. In this case, that was the Crown, who opposed Mr. Verrilli’s application. The Provincial Court judge erred in applying the Michaud test and placing the burden on Mr. Verrilli to provide some evidence that the warrants were unlawfully granted before permitting access to the ITOs.

[37] Concerns about the possibility that disclosure of wiretap ITO information might make future police investigations less effective form part of the rationale related to the Michaud decision. These same issues may arise on applications for discretionary publication bans and sealing orders. Examples can be found in Mentuck and Toronto Star. The difference between the Michaud and Dagenais/Mentuck approaches is not whether protection of investigative techniques can be considered but, rather, where the evidentiary burden lies and how the presumption in favour of open courts is taken into account.

[38] I would dismiss the Crown appeal and, as directed by Justice Arnold, Mr. Verrilli’s application should be remitted to the Provincial Court for disposition in accordance with the applicable principles.

R v Kapustinsky, 2020 ABQB 611

[October 14, 2020] Sexual Assault - s.276 Applications - General Relationship Sexual History [Mr. Justice N. Devlin]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: This decision provides a good overview of the principles in sexual assault cases and specifically how general sexual history in the relationship can affect the defence of consent. Most of the time, sexual history is admitted to explain some course of conduct communicated consent to the accused which would be difficult to tell from an outside perspective without the history of sexual conduct between the parties. Here, the sexual history evidence was permitted because it involved conduct which put the accused unfairly in a very negative light before anything related to the sexual interaction even arose when all that conduct was part of the history of sexual interactions between the accused and the complainant.

Anticipated Evidence

[8] The anticipated evidence is that the accused let himself into a home where the complainant was staying with a friend (RT), using a door keypad code that had been given for this purpose. He came at night, relying on a broad-ranging invitation to attend. He will contend that he messaged the complainant in advance of his attendance. The record is silent on the complainant’s version of their correspondence on the evening in question, and whether she replied.

[9] Inside the residence, the accused found the complainant asleep in a bed beside RT. The complainant’s version is that the accused crawled into bed beside her. She believed it to be someone else and spoke words to that effect. He proceeded with intimate contact. The complainant says she did not consent. She told police that she “was trying to make myself sleep” when he penetrated her, first digitally and then through penile intercourse.

[10] She says she woke up and said to him “what the hell?” After this, she claims to have confronted the accused in the kitchen, where he was having a beer. She recounts him saying that their encounter was consensual and that she had been saying his name. She told him to “to get the fuck out”, after which he left and the complainant awoke her friend and reported the assault.

[12] The accused’s affidavit detailed his sexual history with the complainant. It recounted a series of instances on which they had came together for casual sexual encounters. On a number of those occasions, the complainant arrived unannounced at his home, late at night, and they proceeded to have sex. The key portions states that:

On June 9, 2018, in keeping with our casual open sexual relationship, I attended RT's residence where [the complainant] was staying. I did so by using a code I had been given so I could come and go as and when I pleased. [The complainant]) and I had sex (oral and vaginal intercourse) on at least two occasions at that residence prior to June 9, 2018.

I got into bed with [the complainant]’s and engaged in consensual vaginal intercourse.

[13] This also somewhat vague recounting of events reflects the accused’s desire not to entirely disclose his defence prior to trial. On the accused’s behalf, Mr. Fagan further particularized the application at the hearing by stating that the accused would take the stand 3 and would provide greater detail as to the communication that took place between him and the complainant. The accused will testify that he suggested to the complainant that they move to another room, given that RT was asleep beside them, but that the complainant said something to the effect of “let’s do it here.”

The Evidence Requested by the Accused

[14] At the first stage of the hearing, Mr. Fagan disclaimed reliance on any of the specific sexual activity detailed in his client’s affidavit and made clear that he does not he seek to lead evidence of those prior sexual encounters, including those at RT's home. Rather, he particularized the accused’s evidentiary ask as follows:

That the trier of fact be permitted to learn that the accused and complainant were known to each other and had had a sexual relationship consisting of casual, spontaneous, and sporadic encounters, over the two years preceding the alleged assaults.

[15] The accused argues that, unless the trier of fact knows this about his relationship with the complainant, evidence that he showed up at this person’s bedside, and proceeded to seek and obtain consent, will be seen as implausible and even predatory. This would unfairly, if not fatally, impair the credibility of his version of events, including the critical consent-obtaining interaction he will say took place.

[16] The accused also maintains that, without this background, his potential alternate claim to an honest but mistaken belief in communicated consent could be judged on the wrong standard of what amounted to “reasonable steps” to ascertain consent and/or be unfairly found to lack an air of reality.

The Process of a s.276 Hearing

[20] The admissibility of other sexual evidence is examined in a two-stage proceeding. The first stage is a preliminary screening of the application under section 278.93(2). The defence initiates the process by filing materials that particularize the evidence it seeks to adduce and the mechanism of relevance to an issue at trial. The application materials must provide the information necessary to permit the judge to evaluate the claim of relevance and understand its potential operation within the specific context of the trial. These materials typically include an affidavit from the accused and a summary of the allegations he is facing, whether in the form of a synopsis, a transcript of a statement, or prior testimony by the complainant.

[21] The first stage does not determine ultimate admissibility under 276(3). This preliminary step is meant to screen out those requests to raise other sexual activity which, on their face, are clearly brought for an impermissible purpose: R v JE, 2019 NLSC 134 at paras 47-51. At this point in the process, the Court must be satisfied that the evidence tendered with the application “is capable of being admissible under section 276 (2)”. (s 278.93(4)) [emphasis added]

[22] Only those applications which pass this threshold are sent to a full hearing under s 278.94. Applications which lack sufficient detail risk being summarily dismissed: R v LeBrocq, 2011 ONCA 405 at paras 9 & 10.

[23] The guiding jurisprudence identifies two key questions the Court must ask at the first stage: (i) is the proposed evidence sufficiently well-defined and circumscribed to serve a proper purpose; and (ii) can the accused articulate the mechanism of relevance to which those specific facts relate. A detailed examination of the relevance mechanism, and the overall balancing of interests the probative and prejudicial value of the evidence, are reserved for the full hearing.

[24] The preliminary screening is designed to weed-out meritless uses of other sexual activity evidence which are simply manifestations of the increasingly well-defined archetypes of prohibited reasoning. These are meant to be eliminated summarily, without disruption to the trial process, and without needlessly traversing these sensitive matters.

[25] The threshold for the accused to overcome at the first stage is low. The Court conducts only a facial consideration of the matter, with any doubts that exist as to the admissibility of the evidence best left to the second stage voir dire: R v SL, 2018 ABQB 889 at para 9; R v AM, 2020 ONSC 4541 at para 32. This first stage takes place in camera: s 278.93(3).

[26] At the second stage, a more fulsome voir dire is held, again in camera: s 278.94(1). Evidence may be called and more extensive submissions may be made: s 278.93(4). The complainant is not a compellable witness (s 278.94(2)), but has a right to participate and make submissions through counsel: s 278.94 (3).

Establishing Relevance

[35] Establishing the relevance of the proposed evidence is the linchpin of any section 276 application. To establish relevance, the accused must demonstrate “a connection between the complainant's sexual history and the accused's defence”: Darrach at para 56; Goldfinch at para 113 (per Moldaver J. concurring). Explicit identification of the link between the evidence of other sexual activity and the accused's defence is essential to avoid “twin-myth reasoning slipping into the courtroom in the guise of context": Goldfinch at para 119.

[36] The meaning of “relevance” was helpfully reviewed by Watt JA in R v Jackson, 2015 ONCA 832, leave to appeal to SCC refused 36829 (June 30, 2016), where Watt JA highlighted three key characteristics of the concept at paragraphs 120-122:

Relevance is not a legal concept. It is a matter of everyday experience and common sense. It is not an inherent characteristic of any item of evidence. Some have it. Others lack it.

Relevance is relative. It posits a relationship between an item of evidence and the proposition of fact the proponent of the evidence seeks to prove (or disprove) by its introduction. There is no relevance in the air […]

Relevance is also contextual. It is assessed in the context of the entire case and the positions of counsel. Relevance demands a determination of whether, as a matter of human experience and logic, the existence of a particular fact, directly or indirectly, makes the existence or non-existence of another fact more probable than it would be otherwise […]. [citations omitted]

[37] The task of the applicant under section 276(2) is to articulate the chain of reasoning by which the evidence of other sexual activity becomes properly probative. The tighter and more precise that relationship of relevance is, the less risk the other sexual activity evidence will be misused. The Court must guard against this evidence being admitted on the strength of “generic references to the credibility of the accused.... Credibility is an issue that pervades most trials”, and vague reference to this issue will not suffice to satisfy section 276(2): Goldfinch at para 56.

The Defences at Play

Consent

[40] What “consent” means, and how it operates in sexual assault trials, can be summarized from the Supreme Court’s recent jurisprudence as follows. Specifically, consent:

• is the conscious, voluntary agreement of the complainant to engage in every sexual act in a particular encounter: R v JA, 2011 SCC 28 at para 31; see also s 273.1(1) of the Criminal Code;

• must be freely given: R v Ewanchuk, 1999 CanLII 711 (SCC), [1999] 1 SCR 330 at para 36;

• must exist at the time the sexual activity in question occurs: JA at para 34, citing Ewanchuk at para 26;

• can be revoked at any time; JA, at paras 40 and 43; s. 273.1(2)(e) of the Criminal Code; and

• is not considered in the abstract and must be linked to the “sexual activity in question”, which encompasses “the specific physical sex act”, “the sexual nature of the activity”, and “the identity of the partner”: R v Hutchinson, 2014 SCC 19 at paras 54 and 57.

[41] Importantly, consent is subjective to the complainant: Ewanchuk at paras 26-30. Therefore, consent cannot be found in external factors such as the relationship between the parties or the complainant’s words or conduct on a different occasion: JA at para 47.

Honest but mistaken belief in consent

[42] A number of key principles guide the operation of the defence of honest but mistaken belief in communicated consent. These include that:

• the accused must demonstrate an air of reality to this defence before it will be considered by the trier of fact: Barton, at para 121;

• the accused must take reasonable steps to determine the presence of consent: s 273.2(b);

• the accused’s belief must be about communicated consent. The analysis asks whether the accused honestly believed "the complainant effectively said 'yes' through her words and/or actions": Barton at para 90 citing Ewanchuk at para 47;

• this defence is not available to the accused where “there is no evidence that the complainant’s voluntary agreement to the activity was affirmatively expressed by words or actively expressed by conduct”: s 273.2 (c);

• the test for whether an accused took reasonable steps to ascertain consent is an objective/subjective one. The steps taken by the accused must be objectively reasonable in light of what he personally knew at the time Barton at para 104; and

• passivity is not consent and a belief in silence as consent is a mistake of law and no defence: Ewanchuk at para 51; Barton at paras 105-107.

Ultimate Balancing - Probative v Prejudicial Value

[43] The final condition of admissibility in s 276(2) is that the evidence have "significant probative value that is not substantially outweighed by the danger of prejudice to the proper administration of justice" considering the factors set out in s 276(3): Goldfinch at paras 69 and 128: RV at para 60. This ultimate balance requires a court to determine whether the proposed evidence would unfairly and improperly skew the trial by promoting “twin myth” reasoning, despite the presence of at least tangential relevance: Darrach at para 41. It provides the Court with a final, overall look at the balance of interests in play to ensure that the administration of justice is properly served.

Section 278.93 - Stage One

Accused's Credibility

[47] At this initial juncture, it is sufficient that the accused’s exculpatory version of events is capable of casting him “in an unfavourable light” that makes his evidence “untenable or utterly improbable” if his words and actions are judged absent the information sought to be admitted under s 276: Goldfinch at para 68 per Karakatsanis J; see also R v Temertzoglou, [2002] OJ No 4951 (SC) at para 27. I find that this threshold is met.

[48] The accused entered a home that was not his, at night, while the occupants were asleep. At this point there is no evidence they knew he was coming. He approached the sleeping complainant for the sole and express purpose of commencing a sexual encounter. These bare facts raise obvious questions about what he was thinking, and how he will explain his actions as other than a frightening and predatory incursion into a vulnerable and protected space.

[50] It is essential to re-iterate that a belief by the accused that the complainant might be receptive to his advances because of their existing sexual relationship does nothing to establish that consent was actually given that night: JA at paras 47 and 64. Consent must be found in what specifically passed between the accused and complainant on this occasion.[5]

[51] The relationship evidence could, however, impact the trier’s overall perception of the accused, his relationship to reality, and the credibility of his testimony. This specific articulable link between the relationship evidence, the accused’s state of mind, and how the trier of fact views him as a result, is sufficient to satisfy the first-stage threshold and trigger the requirement for a full hearing on the issue of admissibility.

[52] The more challenging question of whether the differential in the accused’s credibility, as viewed with and without the relationship evidence, outweighs the risk that this information would feed prohibited inferences about consent is addressed in the more fulsome second stage analysis.

Relevance to Honest but Mistaken Belief in Consent

[53] The facts advanced by the accused on this application do not establish the basis for a defence of honest but mistaken belief in communicated consent. This may change once the parties testify at trial and greater detail about their interaction on the night in question is revealed. However, the mere potential that a defence of mistaken believe in communicated consent may yet arise does not satisfy s 278.93(4).

Stage II - The Admissibility Hearing

[57] On the bare facts the accused’s story is incoherent. It begs but does not answer the question: what was he thinking?Moreover, as a matter of logic, why would one have worried about consent in a situation where there is no logical expectation that it be forthcoming? His story is also improbable. People operating under a commonplace conception of how consensual relationships take shape do not ordinarily find themselves at the beside of a sleeping acquaintance in search of sex.[6] Consent is simply not in the air. Indeed, the accused was initially also charged with Break and Enter with Intent for what he had done.[7]

[58] The relationship evidence serves to dispel the cloud of scepticism and disbelief that would otherwise hang over the accused’s claim that he came with good faith intentions to have a consensual sexual encounter. It transmutes his story from untenable to at least coherent.

[59] Examining whether a person’s claimed behaviour accords with common sense, life experience, and reasonable assumptions about how ordinary people can be expected to act, is one of the core mechanisms by which credibility is assessed: R v PFJ, 2018 ABCA 322 at para 14; R v Delmas, 2020 ABCA 152 at para 31, application for leave to SCC filed 39163 (May 14, 2020).

[60] The relationship evidence is thus relevant to the accused’s credibility because it increases the correspondence between his actions and beliefs and the prevailing understanding of how humans normally behave, in a way that overcomes an unfair burden of general disbelief that may infect all facets his testimony.

This use is Contemplated in Goldfinch

[61] The Supreme Court’s decision in Goldfinch affirms that evidence “fundamental to the coherence of the defence narrative”[8] can and should be admitted: at paras 66 & 69. Each sets of reasons in Goldfinch averts to the concern that, in some circumstances, an accused’s version of the events may give rise to an unfair negative impression as to his intentions and credibility unless he can explain it through evidence to which section 276 applies.

[62] The majority’s test for admission of evidence on this basis can be discerned from their reasons for finding that Mr. Goldfinch had not satisfied it:

68 In my view, there is nothing about Goldfinch’s testimony that casts him in an unfavourable light or renders his narrative untenable or utterly improbable absent the information that the two were “friends with benefits”. The complainant's request for "birthday sex" does not reflect on Goldfinch's character or behaviour. As well, her reaction to his comment was a smile -- hardly an indication that this behaviour was beyond the pale of their relationship. Tellingly, the complainant did not deny the call, Goldfinch's comment or the smile. [emphasis added]

[63] The accused in this case falls squarely within Karakatsanis J’s description of someone whose testimony would be “untenable” and “utterly improbable” if the relationship evidence is withheld, making it fundamental to full answer and defence (Mills, at paras 71 and 94).

[64] In his concurrence at para 123, Moldaver J similarly held that relationship evidence should be permitted where the accused’s testimony as to his actions and words would otherwise come across as unbelievable...

[66] The unifying theme that emerges from each set of reasons in Goldfinch is that the exclusionary rule in section 276 must not be used to place the accused, and his evidence, in an artificially worsened light. The sharp split between judges at all levels of court in Goldfinch illustrates the difficulty in defining when an unfair burden of disbelief will arise. Those courts were unanimous, however, that other sexual activity evidence may become relevant when it does.

[67] I find that this accused would face such an unfair burden, and that the relationship is relevant to him making full answer to it.

Evidence Operates on Accused Credibility, not Likelihood of Consent by Complainant

[72] Conversely, however, Goldfinch is not a command that courts ignore circumstances in which the accused’s sexual advances or activities will seem inherently predatory, abusive, or driven by a distorted understanding of consensual intimate relationships unless he can point to some objective basis for believing that his actions would be welcomed. Section 276 does not condemn accused individuals to face trial under an equally unfair burden of general disbelief in such situations.

Honest but Mistaken Belief in Consent

[79] The relationship evidence in this case does not assist the accused in establishing that consent was communicated on this specific instance. However, I find that the absence of relationship evidence would be an almost insurmountable roadblock to establishing that anything which passed between the accused and the complainant in this case could reasonably be construed as free and willing consent. For this reason, the relationship evidence would be relevant to a defence of honest but mistaken belief in communicated consent, if it comes into play.

Balancing Probative Value v Prejudicial Effec

[80] Once the relevance of other sexual activity evidence has been established, the Court must further consider whether it has “significant probative value that is not substantially outweighed by the danger of prejudice to the proper administration of justice” (s 276(2)(d)). This balancing process is driven by the factors enumerated in s 276(3), and was explained in Goldfinch at para 69 in the following way:

Balancing the s. 276(3) factors ultimately depends on the nature of the evidence being adduced and the factual matrix of the case. It will depend, in part, on how important the evidence is to the accused’s right to make full answer and defence. For example, the relative value of sexual history evidence will be significantly reduced if the accused can advance a particular theory without referring to that history. In contrast, where that evidence directly implicates the accused’s ability to raise a reasonable doubt, the evidence is obviously fundamental to full answer and defence (Mills, at paras. 71 and 94). [emphasis in original]

[81] The relationship evidence in this case meets the requisite threshold for probative value (ss 276(3)(3)(b-c). Its absence would materially and unfairly impede the accused’s credibility as to his acts and state of mind: Darrach, at paras 38-43. This evidence is required for the accused to face trial on a level playing field.

Dangers of Admitting Relationship Evidence

[82] The countervailing risk of prejudice takes two forms: a continued risk of prohibited inferences taking hold where other sexual activity evidence is properly admitted, and incursions into the privacy and dignity of the complainant. Notwithstanding relevance, the Court must remain alive to the concern that the evidence of prior encounters will, albeit indirectly, invite the impermissible inference that the complainant more likely consented in the present instance: Goldfinch at paras 58-59.

Mitigating the Risk

[85] In this case, the risks associated with admission of the other sexual activity evidence are attenuated in three ways: (i) use of an agreed statement of fact; (ii) absence of any salacious details; and (iii) election to be tried by judge alone.

[87] In cases where the relevance of the other sexual activity evidence relates to the accused’s credibility or state of mind, an agreed statement of facts may often be the preferred route for this evidence to be introduced for exactly these reasons. Unless the complainant’s credibility is directly implicated, it is difficult to see any advantage to this evidence being introduced through viva voce evidence.

[89] The neutral wording of the agreed statement of facts also removes any salacious element from the evidence in this case. This avoids any risk of distraction, undue embarrassment, or sensationalism surrounding the sexual nature of that evidence, and satisfies the concerns raised by sections 276(3)(b,d,g). It would also allay the concern about arousal of prejudice in the mind of the jury if the accused had maintained his original election (s 276(3)(e)).

[90] Perhaps even more importantly, nothing in the agreed statement of facts would suggest that the sexual activity between the complainant and accused was “routine” and “typical”. Language of that nature was of particular concern to the majority in Goldfinch (at para 72), as it infers a straight line of reasoning from past consent to present consent, elevating the risk of prejudicial reasoning. The proposed statement of the evidence removes the “unfavourable light” in which the accused’s evidence would otherwise be viewed in a way that does not tip over into inferring that the complainant was prone to consent based on their past relationship. I find that this is the correct balance for both of the individuals touched by this case to receive the full protection and benefit of the law: s 276(3)(g).

[91] Finally, the accused’s re-election to trial by judge alone further limits the potential prejudice as it reduces the risk that the trier of fact might apply stereotypical or discriminatory reasoning. The availability of appellate review of judicial reasons offers a further check on this concern, answering ss 276(3)(d-e).

Conclusion

[92] The accused is permitted to lead evidence to the effect that he and the complaint were acquainted and had a casual, sporadic sexual relationship for a period preceding the events that led to him being charged. Defence and Crown will cooperate to prepare an agreed statement of facts that will form part of the record before me at trial. This is the extent to which the prior sexual history of the parties is admissible.

R v Savage, 2020 ABQB 618

[October 15, 2020] – Impaired/Over 80 - s.8: Failure to Comply with 15-minute Observation Period [Madam Justice A. Loparco]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: The onus on a s.8 violation where a search occurs without a warrant is always on the Crown to justify the search. In this case, the onus meant the Charter was a better argument than arguing doubt about the presumption of accuracy. The discrepancy between the 15-minute recommended observation period and the time actually observed was a mere 2 minutes. This 2 minutes, because it was not specifically addressed by the judge was sufficient to raise a compelling ground of argument resulting in a new trial.

Overview

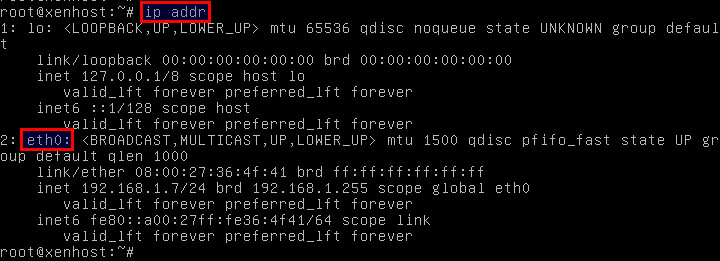

[1] On November 23, 2018, near Rainbow Lake, Alberta, Constables Laurin and Kaiser stopped Ms. Savage’s (the Appellant’s) vehicle for a document check. As they suspected impairment, an Approved Screening Device test was conducted roadside, resulting in a fail. The Appellant was arrested and placed in the RCMP vehicle. They left the scene at 12:17am and arrived at the Chateh police detachment at 12:58am for further testing.

[2] At the detachment, two standard tests were performed with the breathalyzer 1 before each of two samples were taken from the Appellant. One sample was taken at 1:11am, and the other at 1:32am. The first standard test performed is the ‘air blank test’, which tests the ambient air to detect any alcohol (defence counsel refers to this as the diagnostic test). The second test performed is the ‘diagnostic test’ (defence counsel refers to this as the calibration test), which tests against a known standard. The first sample reading was recorded as 140mg% and the second as 120mg%.

[3] Following a trial, the Honourable Judge Ambrose convicted the Appellant of operating a motor vehicle with a proscribed concentration of alcohol in her blood contrary to s. 253(1)(b) of the Criminal Code as it existed prior to December 18, 2018.

Analysis - s.8 Requirement to Comply with the 15-minute Observation Period

[14] At trial, Ms. Savage argued that the officer did not properly conduct the observation period before taking the breath samples at the detachment. In determining whether the search and seizure of the breath samples was conducted in a reasonable manner, the trial judge first noted that the manufacturers of breathalyzers prescribe an observation period to ensure an accurate measurement of blood alcohol content of a test subject.

5] The trial judge correctly noted that a test subject must not have residual mouth alcohol when a breath sample is provided because this can result in an inaccurate result. He then noted that “the presence of residual mouth alcohol can arise from indigestion of any substance that contains alcohol or it can arise from unabsorbed alcohol from the stomach or gastrointestinal tract, which is introduced into the mouth by regurgitation or burping”: Trial Transcript at 4.

[17] The next event chronicled was a period of an hour and 15 minutes that passed during which the accused was under arrest and being transported to the detachment, and then being processed while awaiting the first breath sample. The judge found that there is no possible inference that the accused had ingested any substance between the initial traffic stop and the provision of the first breach sample at the detachment.

[18] He further found that there was no evidence that Ms. Savage had burped in the police cruiser or at the detachment. He held that Ms. Savage was continually observed from the time of arrival at the police station to the time the first breath sample was provided....

[28] In many impaired driving cases, including Cyr-Langlois and R v So, 2014 ABCA 451, an accused driver argues that the Crown cannot rely on the presumption of accuracy found in sections of the Criminal Code. Such cases are also referred to as “evidence to the contrary” cases. In this case however, the accused bases her arguments on the Charter. Specifically, the Appellant argues that the warrantless search and seizure resulting in her breath samples was not reasonably conducted because of the failure to observe the 15-minute period in consideration of the totality of circumstances, and thus, it violated her s. 8 rights under the Charter.

[30] Cyr-Langlois went through three levels of court before the Supreme Court of Canada agreed with the summary conviction appeal judge (who relied on and cited So). The SCC held that the issue in the case was to establish what an accused must do to rebut the presumption of accuracy that is applicable to breathalyzer results. The Court concluded that the accused’s burden is discharged if: 1) the accused adduces evidence relating directly to the malfunctioning or improper operation of the instrument; and 2) the accused establishes that this defect tends to cast doubt on the reliability of the results.[2]

[32] Neither Cyr-Langlois nor So included arguments about s. 8 of the Charter.

[35] With respect to the first issue, I find the trial judge misunderstood the arguments and misinterpreted the evidence. This led the trial judge to fail to adequately apply the proper analysis in determining whether the search and seizure of the breath samples at the detachment was conducted reasonably. Unfortunately, the trial judge did not have the benefit of the decision McManus, in which Henderson J determined, at para 36, that whether breath samples are obtained in a reasonable manner (pursuant to s. 8 of the Charter) must be determined by assessing the totality of circumstances. Evidence as a whole must be considered to determine reasonableness.

[36] McManus was heard and released after the trial judge gave this decision and, as mentioned, the trial judge did not have the benefit of McManus. I agree with Henderson J as to the proper analysis and assessment necessary in this matter.

[37] Section 8 of the Charter states that: “Everyone has the right to be secure against unreasonable search and seizure”. As noted in McManus at para 17, “…because taking a breath sample from an accused person is done without a warrant, the search or seizure is presumptively unreasonable and thus the Crown has the onus to justify the search” (citations omitted).

[38] Although the Criminal Code does not require that the police observe a suspect for 15 minutes prior to taking a breath sample, and in some cases, it may not be required to prove that the search was reasonable (R v Bernshaw (1994), 1995 CanLII 150 (SCC), [1995] 1 SCR 254), the failure to observe the full observation period recommended for a device needs to be assessed in relation to the s. 8 Charter breach allegations.

[39] At para 36 of McManus, Henderson J set out the factors to be assessed in the context of a s. 8 Charter breach allegation:

i. The 15-minute observation period has no statutory authority and therefore the failure to comply with it does not automatically mean that the breath samples were taken in an unreasonable manner;

ii. Failing to comply with the 15-minute observation period in a manner consistent with their police training is a factor that may shed light on the circumstances and may explain whether the approved instrument was used improperly which, in turn, may impact the reasonableness of the manner in which the breath samples were taken;

iii. Whether breath samples are obtained in a reasonable manner must be determined by assessing the totality of the circumstances. It is an error to test individual pieces of evidence. Instead, the evidence as a whole must be considered to determine reasonableness;

iv. Failure to comply with the 15-minute observation period is one factor which must be assessed as part of the totality of the evidence in determining reasonableness.

v. The reasonableness of the manner of taking the breath samples must be assessed in the context of the need to satisfy the requirements of s 254(3) that the samples be taken “as soon as practicable” although there is some flexibility in the operation of this requirement. (emphasis in the original)

[40] I find that the trial judge did not adequately review the totality of circumstances to determine whether the Crown discharged its burden in finding a reasonable seizure of the Appellant’s breath samples at the detachment. Specifically, the trial judge commented on facts and considered arguments that were not in issue. For example, the trial judge made specific comments and findings on the reasonableness of the seizure of the accused’s breath samples during the roadside test, which does not appear to have been in issue.

[41] The trial judge clearly and specifically addressed the fact that the police did not wait 15 minutes after initiating the traffic stop before administering the roadside test.

[42] However, in contrast to discussion about the observation period at the roadside, the trial judge failed to address the fact that only 13 minutes elapsed between the time the Appellant arrived at the detachment to the time the first breath sample was taken. While I recognize that the 15-minute observation period it is not a statutory requirement, both officers testified to their understanding that this observation period was required for the proper functioning of the device. Further, Cst. Laurin testified that this period was essential in order to be able to rely on the results.

[43] The importance of the full observation period was also emphasized long ago by the Supreme Court of Canada in Bernshaw at para 57: “In order to ensure that the results of the test are not falsely elevated, one must wait an adequate period of time so that any mouth alcohol present has had an opportunity to dissipate.” Thus, an assessment of all factors at play that would lead to a conclusion as to why it did not need to be complied with was necessary.

[44] Despite makings findings about the observation period before the roadside test (which was not an issue), and hearing a plethora of evidence about observation periods and their importance, the trial judge did not specifically address the fact that only 13 minutes elapsed between the time the party arrived at the detachment and the first breath sample was provided.

[45] While the trial judge found continuous observation at the detachment, this could only have been, at best, observation of 13 minutes, rather than the 15 minutes provided for in the testing protocol. As in McManus, given the deferential standard owed to the trial judge, I find no error in relation to this finding of fact. However, the trial judge could not have considered the totality of the circumstances if he failed to address why the standard 15-minute observation period that was cut short by two minutes did not render the search unreasonable in this case. In failing to address this – one way or another – I find the trial judge failed to conduct the appropriate analysis necessary to determine whether breath testing is conducted reasonably.

[48] I agree with the Appellant that the trial judge relied on such extraneous evidence to infer that an unusual occurrence would not have taken place. Notably, the trial judge found that there could not have been unabsorbed alcohol in Ms. Savage’s stomach. This finding, along with others made by the trial judge, appears to be the kind that would be found in a case where the accused argued that the Crown could not rely on the presumption of accuracy found in the Criminal Code. However, as noted, the Appellant here instead alleged a breach of her s. 8 Charter rights based on an unreasonable search and seizure.

[49] The trial judge made a finding that nothing in the Appellant’s stomach could have caused a burp or regurgitation that would skew the results of the breath sample. This finding about unabsorbed alcohol in the Appellant’s stomach appears to have been material to the determination that search and seizure of the breath sample was conducted reasonably. The trial judge may have relied on his findings about a lack of unabsorbed alcohol (which was not in evidence) to find that imperfect conduct in the taking of the breath samples was insignificant or unimportant, and thus the search and seizure was conducted in a reasonable fashion.

[50] ... He also noted that neither officer could say whether the Accused had burped during the drive to the detachment, but that it did not matter because there was no possibility the Accused could have had unabsorbed alcohol in her stomach by the time she arrived at the detachment. The trial judge failed to note that any observation was limited during that drive due to street noise, the silent patrolman divider being closed, darkness, among other factors. In short, concluding that there could be no unabsorbed alcohol in the accused’s stomach would involve a complex analysis; it would not be possible to reach this conclusion without established facts and, possibly, the assistance of an expert. The trial judge’s conclusion is not based on notorious or indisputable sources, nor is it a ‘common sense inference’ as in Flight at para 78.

[52] In conclusion, an accused who alleges a Charter breach has the onus to prove the violation on a balance of probabilities, but the onus shifts to the Crown when it is established to be a result of a warrantless search. As this was not an “evidence to the contrary case”, the accused had no onus to prove that the lack of compliance with the observation period cast doubt on the reliability of the results through mouth alcohol caused by burping, belching, or vomiting. As the only issue was whether the breath samples were taken in a reasonable manner, with the onus on the Crown to prove that it was. Speculation as to any unusual occurrence happening was not required and thus, the reference to extraneous information to establish its absence was an error.

[92] Having found errors on both Grounds One and Two, I allow the appeal, set aside the Appellant’s conviction, and remit this matter back for a new trial.