This week’s top three summaries: R v Brown, 2019 ONSC 1471, R v Cantwell, 2019 ABPC 50, and R v Pireh, 2019 ABPC 52.

R. v. Brown (ONSC)

[Mar 5/19] Probative v Prejudicial Value - Prior Violent Acts of Accused - 2019 ONSC 1471 [M. Forestell J.]

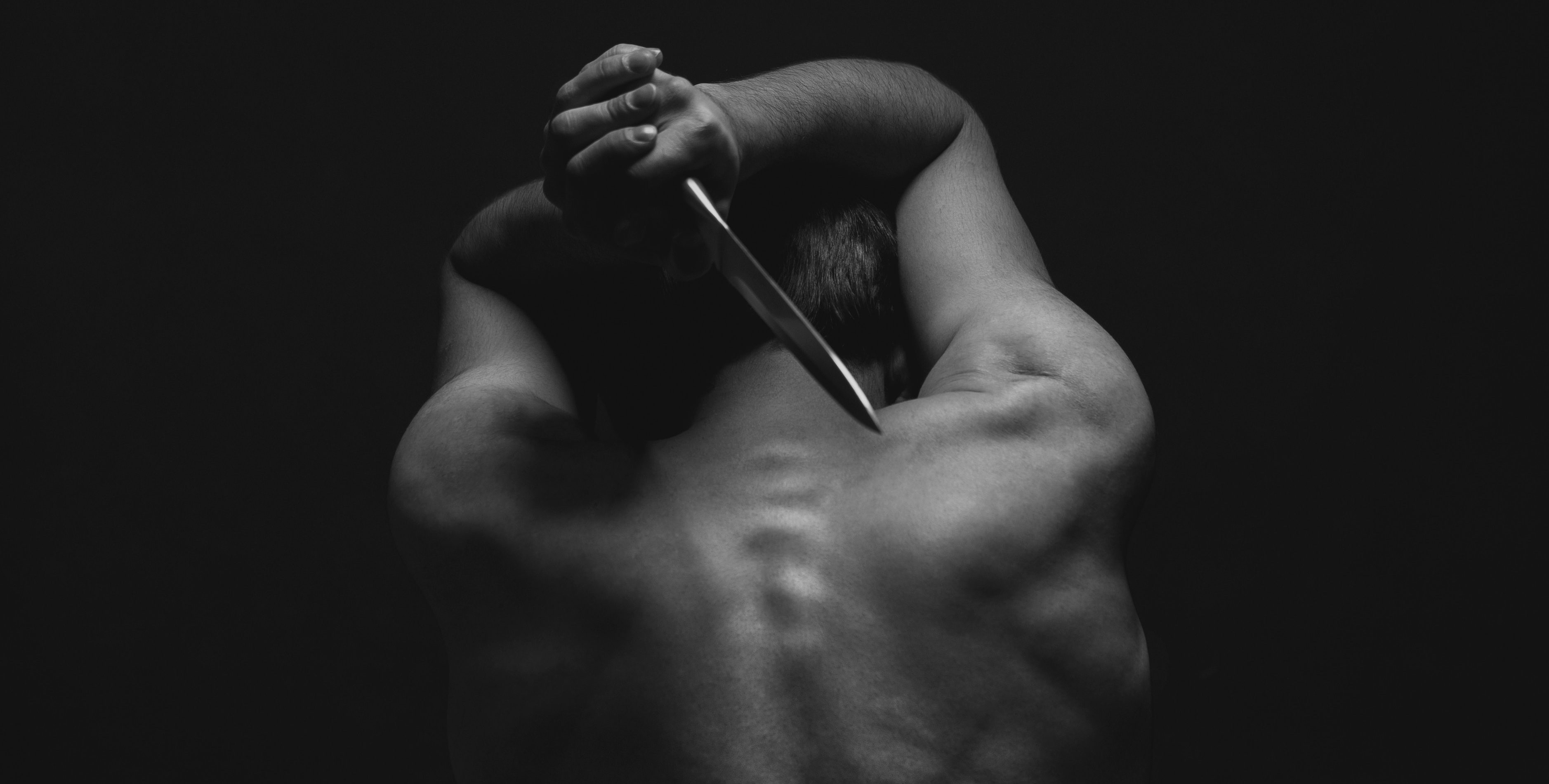

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Here, Justice Forestell gives a very useful summary of the law in the area of probative v prejudicial value assessments. The application involved a prior use of a knife by the accused in against co-tennants in a rooming house where he was ultimately charged with murder with the use of a knife. The exclusion is a good example of the analysis required to exclude evidence that can be used for propensity reasoning. NOTE: Case presently available on Westlaw in full.

Pertinent Facts

"Deon Brown is charged with the second degree murder of Tevone Wright. Mr. Wright was stabbed by the accused on August 22, 2017 during an altercation in a rooming house where they both lived. It is not disputed that the accused caused the death of Mr. Wright. The issues in the trial are the state of mind of the accused and whether he acted in self-defence. The trial began before me on February 4, 2019 with a voir dire into the admissibility of evidence of prior discreditable conduct of the accused." (Para 1)

"In the pre-trial application, the Crown applied for a ruling that evidence ... was admissible: [particularly] A confrontation that occurred approximately 2 to 3 weeks prior to the stabbing of the deceased in which it is alleged that the accused chased Everton McDonald and another tenant, Leonard Augustine, out of the backyard of the rooming house with a knife because the two were making too much noise." (Para 2)

"In his evidence-in-chief on the voir dire, Mr. McDonald first testified that the incident occurred when he was in the kitchen and the accused got mad because Leonard Augustine, another tenant, was playing music. The accused became angry at Mr. McDonald because Mr. McDonald said something. Mr. McDonald then corrected himself and testified that the confrontation occurred in the backyard. He said that he and Mr. Augustine were in the yard playing music when the accused came to the patio door and told them to stop playing music. The accused had a knife in his hand that Mr. McDonald described as a "small machete". He testified that it was a different knife than the one used to stab the deceased. Mr. McDonald testified that the accused tried to chase them off the property" (Para 14)

Probative v Prejudicial Value

"Evidence of extrinsic misconduct of the accused is presumptively inadmissible. Such evidence may be admissible where the evidence has probative value that outweighs its prejudicial effect. The law governing the admissibility of discreditable conduct of the accused is set out in R. v. B.(L).:

Because of the inherently prejudicial nature of evidence of discreditable conduct, it is subject to a general exclusionary rule unless the 'scales tip in favour of probative value.' The trial judge who is charged with the delicate process of balancing the probative value of the proposed evidence against its prejudicial effect should inquire into the following matters.

- Is the conduct, which forms the subject-matter of the proposed evidence, that of the accused?

- If so, is the proposed evidence relevant and material?

- If relevant and material, is the proposed evidence discreditable to the accused?

- If discreditable, does its probative value outweigh its prejudicial effect?" (Para 27)

"The probative value of the evidence is assessed in relation to the issues in the trial. In R. v. Handy, Binnie J. explained that the Crown must identify the live issue in the trial to which the evidence of disposition is said to relate. If the issue is not in dispute, the evidence is irrelevant and must be excluded. The relative importance of the issue is also considered in assessing probative value." (Para 28)

"Some of the other factors to consider in the assessment of the probative value of the evidence are the proximity in time to the alleged offence, the similarity of the other acts, the circumstances surrounding the other acts and the offence, any distinctive features of the other acts and the offence, any intervening events and the possibility of collusion." (Para 31)

"The probative value of the evidence must be weighed against the potential for prejudice. As the Supreme Court explained in Handy, prejudice is the " . . . risk of an unfocussed trial and a wrongful conviction" [Emphasis original]." (Para 32)

"The proposed evidence must be assessed to determine the risk of moral or reasoning prejudice. Moral prejudice is the risk of the jury inferring guilt from a general disposition or propensity. Reasoning prejudice is the distraction of the jury from their proper focus, the consumption of time in dealing with multiple incidents and unfairness to the accused because of his limited opportunity to respond to the other incidents." (Para 33)

"The proper approach to the assessment of prejudice was described in R. v. B.(L.) as follows:

In assessing the prejudicial effect of the proposed evidence, consideration should be given to such matters as:

(i) how discreditable it is;

(ii) the extent to which it may support an inference of guilt based solely on bad character;

(iii) the extent to which it may confuse issues; and

(iv) the accused's ability to respond to it." (Para 34)

Application to the Facts

"The previous incident is supportive of the inference only by reasoning that the accused has a propensity to respond violently and unreasonably." (Para 37)

"The evidence is also capable of supporting the other inference advanced in argument: that there was tension between the accused and other tenants and that the tension was caused by the accused's conduct. The inference of tension, however, is only an inference of tension between the accused and two tenants other than Mr. Wright, the deceased." (Para 38)

"It is capable of supporting an inference that the accused has a propensity to respond unreasonably to conflict with co-tenants. This inference involves propensity reasoning. The probative value of the evidence is diminished by the weakness of its support of the inference and by the weakness of the evidence. Mr. McDonald's inconsistent versions of events and the inconsistency with Mr. Augustine's account make the evidence less than compelling." (Para 44)

"I find that the proposed evidence is highly prejudicial. It risks both moral and reasoning prejudice. Although the alleged conduct is not as serious as the conduct that is charged in this case, it is violent criminal conduct. There is a real risk that the jury will engage in general propensity reasoning." (Para 46)

"The jury can only assess the reasonableness or unreasonableness of the accused's response by considering the full context. This would distract the jury and consume undue time on an issue that is of little assistance in the central determination of the reasonableness of the accused's response on August 22, 2017 in different circumstances and with a different party." (Para 47)

"I find that the very limited probative value of the evidence of the alleged interaction between the accused and Mr. McDonald and Mr. Augustine is far outweighed by the prejudicial effect. The evidence is weak and the challenge to the allegations risks consuming undue time and distracting the jury. The probative value is contingent on the context and history of the relationship between the parties which also entails a distracting inquiry. Additionally, there is a real risk of the jury engaging in general propensity reasoning." (Para 48)

The evidence was excluded.

R v Cantwell (ABPC)

[Feb 27/19] Colour of Right - Mistake of Law - 2019 ABPC 50 [F.K. MacDonald Prov. J.]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: The Colour of Right defence is a rare creature in criminal law. Typically, a mistake of law is no defence, but colour of right provides an exception to that principle. Here Judge MacDonald outlines the test and an example of its application leading to an acquittal for a man charged with mischief and extortion for booting vehicles on private property.

Pertinent Facts

"Mr. Cantwell is the owner of a company which puts Denver Boots on trespassing motorists who park in no parking zones on private property. On the 1 st day of June, 2017 Mr. Cantwell's employees put a boot on the complainant, David Lee's vehicle. The signage at the parking lot where Mr. Lee Parked indicated that a trespassing motorist would have to pay a $300 fine to have the boot removed. Mr. Lee phoned the police instead. Mr. Cantwell was arrested and charged with mischief and extortion in relation to his "booting" Mr. Lee's truck." (Para 1)

"David Lee is a labourer who does concrete work. On June 1 st , 2017 he was working at a construction site at 3503 James Mowatt Trail. On that date he was unable to park in his regular parking area in the parkade. Consequently he parked in the visitor's parking area right near the job shack for his construction company on the adjoining property, 3315 James Mowatt Trail. He arrived at 9:00 am. He returned at about 1:30 pm and found that a Denver boot (hereafter "the boot") had been placed on his vehicle. A Denver boot is a device which is designed to clamp onto a motor vehicle wheel. The device prevents the vehicle from being moved." (Para 3)

"Someone from that Company appeared — Mr. Cantwell. Mr. Lee told Mr. Cantwell that he had phoned the police. Mr. Lee was in turn told by Mr. Cantwell that he was being detained for petty trespass and that he should wait for the police. Mr. Lee identified Mr. Cantwell in court." (Para 5)

"[Mr. Cantwell] contacts with property owners who don't have the option for parking enforcement on their property because government programs are not efficient enough to provide for the needs of commercial operations. He signs a contract with the property owner and the property owner gives him the rules and regulations for the parking protocols on their property. Mr. Cantwell posts signage in accordance with the protocol. He stated that generally he leaves the sign up for a week before they start operation. After that they boot cars. The immobilized vehicles belong to people who violate the parking rules." (Para 38)

"On December 3rd of 2016 he was charged with mischief and extortion in Sherwood Park for booting vehicles. Those charges were withdrawn on February 2nd 2017 and he was told by the RCMP that booting was a civil matter and that he could continue with his business." (Para 45)

After searching laws, bylaws, and common law, the court could find no legal basis for someone to boot other people's cars on private property, however...

The Law of Colour of Right

"Section 429(2) specifically extends the defense of colour of right to the offense of mischief. That section reads as follows:

No person shall be convicted of an offence under sections 430 to 446 where he proves that he acted with legal justification or excuse and with colour of right." (Para 108)

"The Supreme Court of Canada defined "colour of right" in R v Simpson, 2015 SCC 40; In that case, Justice Moldaver, writing for the Court said the following:

In R. v. DeMarco (1973), 1973 CanLII 1542 (ON CA), 13 C.C.C. (2d) 369 (Ont. C.A.), at p. 372, Martin J.A. described the term "colour of right" in that section as follows:

The term "colour of right" generally, although not exclusively, refers to a situation where there is an assertion of a proprietary or possessory right to the thing which is the subject-matter of the alleged theft. One who is honestly asserting what he believes to be an honest claim cannot be said to act "without colour of right", even though it may be unfounded in law or in fact. ... The term "colour of right" is also used to denote an honest belief in a state of facts which, if it actually existed would at law justify or excuse the act done. ... The term when used in the latter sense is merely a particular application of the doctrine of mistake of fact. [Citations omitted.] [32] To put the defence of colour of right into play, an accused bears the onus of showing that there is an "air of reality" to the asserted defence — i.e., whether there is some evidence upon which a trier of fact, properly instructed and acting reasonably, could be left in a state of reasonable doubt about colour of right: R. v. Cinous, 2002 SCC 29 (CanLII), [2002] 2 S.C.R. 3, at paras. 49-53 and 83. Once this hurdle is met, the burden falls on the Crown to disprove the defence beyond a reasonable doubt." (Para 109)

"Colour of right was also considered in R v Howson by both CJO Porter and Justice Laskin." (Para 111)

"At para. 25 CJO Porter said the following:

There is no offence if there is colour of right. If upon all the evidence it may fairly be inferred that the accused acted under a genuine misconception of fact or law, there would be no offence of theft committed. The trial tribunal must satisfy itself that the accused has acted upon an honest, but mistaken belief that the right is based upon either fact or law, or mixed fact and law. (Para 112)

"At para. 49 Laskin stated the following:

Accepting that colour of right embraces belief in either matters of law or of fact justifying the challenged taking or detention, the authorities are clear that it must be an honest belief even though a mistaken one...."(Para 113)

"Section 19 of the Criminal Code states "Ignorance of the Law is no excuse." However, colour of right does partake of mistake of law." (Para 114)

Application of the Law

"I am satisfied that he did for the following reasons. One, it is clear that the statute law does not proscribe booting. It very clearly limits it under section 77 of the Traffic Safety Act. However, Mr. Cantwell was correct when he stated that there is nothing in the Traffic Safety Act or the Parking Bylaw which forbids booting by a private property owner. See pp. 75, ll. 29-41; p. 76. ll. 1-26. Two, although he had been three times charged for this practice, none of the prosecutions went ahead — as discussed above. Three, as noted above, he also testified that he was told by a Sherwood Park RCMP officer that booting was a civil matter: see page 62, ll. 30-32. I accept that he thought that he was enforcing what he believed to be the legitimate rights of the property owners as against trespassers." (Para 118)

"I am satisfied that his belief was a reasonable one in light of his experiences in this province. Certainly, the fact that the Crown did not proceed with two prosecutions against him — and withdrew on a third — could in my view reasonably lead to the belief that his actions were lawful. Likewise, the remark of the RCMP to him would, in my view reasonably reinforce that belief. His belief is based on more than a mere moral belief in a colour of right. It is formed by his experiences with booting in this province and elsewhere in Canada, compounded with an honest but mistaken belief in the powers that a private property owner has to remedy a trespass." (Para 119)

R v Pireh (ABPC)

[Mar 4/19] – Charter s.24(2) - Exclusion of Handgun, Ammunition, Cocaine – 2019 ABPC 52 [T.C. Semenuk Prov. J.]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: The prior s.8 violation was summarised in a prior Toolkit here: R v Pireh, 2018 ABPC 291.

The decision summarises and applies a good deal of recent 24(2) decisions from appellate authorities. Ultimately, the case represents the adoption of the ONCA approach in Omar to different factual circumstances in Alberta. When the first two factors in Grant weigh in favour of exclusion of evidence, it should be a rare case where inclusion is the result.

Pertinent Facts

"In my prior ruling at paras. 133 - 139, I stated as follows:

[137] When viewed objectively, the limited information available to the police as to what may have been going on in the accused's suite, what they saw at the scene, and their conversation with the accused at the door, did not give rise to an emergency situation that would entitle this Court to view the code 1014 - causing a disturbance call as analogous to a 911 call. This case boils down to a complaint made by a disgruntled neighbour about sounds... "people being thrown around, yelling, thumping and banging, isn't sure if it's fighting or playing..." coming from the suite occupied by the accused and three other males in their 20's, no women or children or anyone being in distress mentioned.

[138] The Crown has failed to satisfy me on the balance of probabilities that the police had reasonable grounds to enter the accused's suite pursuant to their common law duty to ensure the safety of everyone that may have been in the suite." (Para 5)

Charter Section 24(2)

"Having found a violation of section 8 of the Charter, and having regard to the principles enunciated by the SCC in Grant, for the exclusion of evidence pursuant to section 24(2) of the Charter, the Court is to conduct a balancing test after conducting a three-prong inquiry to assess the following:

- The seriousness of the breach

- The impact of the breach on the accused's Charter protected right; and

- The desirability of a trial on the merits." (Para 10)

Seriousness of the Breach

"where the Court finds that the police lacked reasonable grounds to support their honest subjective belief that their entry into the accused's residence was authorized by law. I agree with the view expressed by the BCCA in Smith at para. 61, that an honest belief connotes an honest and reasonably held belief. If the belief is honest but not reasonable, this is not good faith. The SCC in Paterson at para. 44, confirmed this view." (Para 15)

"As to his assessment of the seriousness of the breach in Zouhri, Renke J., after citing Paterson and Larson, at para. 168, stated as follows:

168 And that - a "moderately serious breach" - is my finding in this instance. There was subjective good faith. There was a failure to follow well-established rules. There was no objective basis on which the officers could and should have entered Mr. Zouhri's residence, but we are not dealing with recklessness or bad faith. The breach was not at the most serious end of the spectrum." (Para 18)

The Court highlighted the following portions of R v Omar:

- "While the police may not have acted in bad faith in this case, an absence of bad faith does not amount to good faith" Omar at para 45.

- "Accordingly, claims of good faith should be rejected if based upon ignorance or an unreasonable application of established legal standards." Omar at para 46.

- "While the police may not have acted maliciously or with the deliberate intention of violating the Charter, they did act in apparent ignorance of the appellant's well-defined Charter rights. That makes the Charter-infringing state conduct serious" Omar at para 48.

Application - Seriousness

"In the case at bar, the police had nothing more than an ambiguous complaint (ie., noise that sounded like fighting or playing), to lawfully justify their entry into the accused's suite. The complaint itself was, in part, not reliable (ie., no smell of marihuana coming from the accused's residence). There was no evidence of any extenuating circumstances, urgency or necessity in this case. When the police arrived at the door to the accused's suite, it was silent. Unlike the case in Zouhri, the accused answered the door. Both he and Eskandar appeared sober, clam and no injuries. In terms of lawfully justifying the police entry into the accused's suite, it is no jump for this Court to conclude that there was an informational deficit. The police ought not to have concluded that there was enough evidence to lawfully justify their entry into the accused's suite to ensure the lives and safety of everyone in the suite." (Para 19)

"Having regard to Zouhri and Omar, I conclude that there was no good faith in this case because the honest belief held by police was not reasonable." (Para 21)

"As in Zouhri, I conclude that the breach in this case was "moderately serious" and favours exclusion of the evidence." (Para 23)

Impact of the Breach on the Accused

"In the circumstances of this case, the accused's Charter protected right was in relation to his private residence. The SCC in Silveira at para. 148, and more recently in Paterson at para. 49, has confirmed that there is a high expectation of privacy in one's home. Not only from the perspective of the accused, but also society at large, when the privacy of one's home is at stake, the impact of the breach by police is to be looked at by the Court with the utmost seriousness." (Para 25)

"The breach of the accused's privacy interest in his own residence in this case is significant and favours the exclusion of the evidence." (Para 26)

Society's Interest in Adjudication on the Merits

"In my view, society's interest in an adjudication on the merits in this case favours admission." (Para 29)

Balancing

In balancing the Court highlighted the following case law commentary:

- "As Doherty J.A. held in McGuffie, at para. 63: "[i]f the first and second inquiries make a strong case for exclusion, the third inquiry will seldom, if ever, tip the balance in favour of admissibility." This approach, although not a binding formula, has been widely followed because a strong case for exclusion supported by the first two grounds is apt to require the exclusion of reliable, even crucial evidence if the repute of the administration of justice is to be protected." Omar at para 53.

- "Cases in which a court must decide whether to exclude probative evidence of a serious crime are always challenging. However, the seriousness of the offence "has the potential to cut both ways" in assessing whether evidence should be excluded (Grant, at para. 84; see also Paterson, at para. 55). Indeed, "while the public has a heightened interest in seeing a determination on the merits where the offence charged is serious, it also has a vital interest in having a justice system that is above reproach" (Grant, at para. 84)." Reeves at para 67

"Having regard to Zouhri, Omar and Reeves, I am of the view that after a proper balancing of the three Grant factors, the evidence sought to be admitted in this case ought to be excluded so as to preserve the reputation of the administration of justice in the long-term." (Para 32)