This week’s top three summaries: R v Le, 2019 SCC 34, R v Sanderson, 2019 SKQB 130, and R v Bartholomew, 2019 ONCA 377.

R. v. Le (SCC)

[May 21/19] Detention - Policing of Racial Minority Communities - Charter s.9 - Detention on Private Property - 2019 SCC 34 [Majority Reasons by Brown and Martin JJ. (Karakatsanis J. concurring). Moldaver J. (Wagner C.J.) Dissenting]

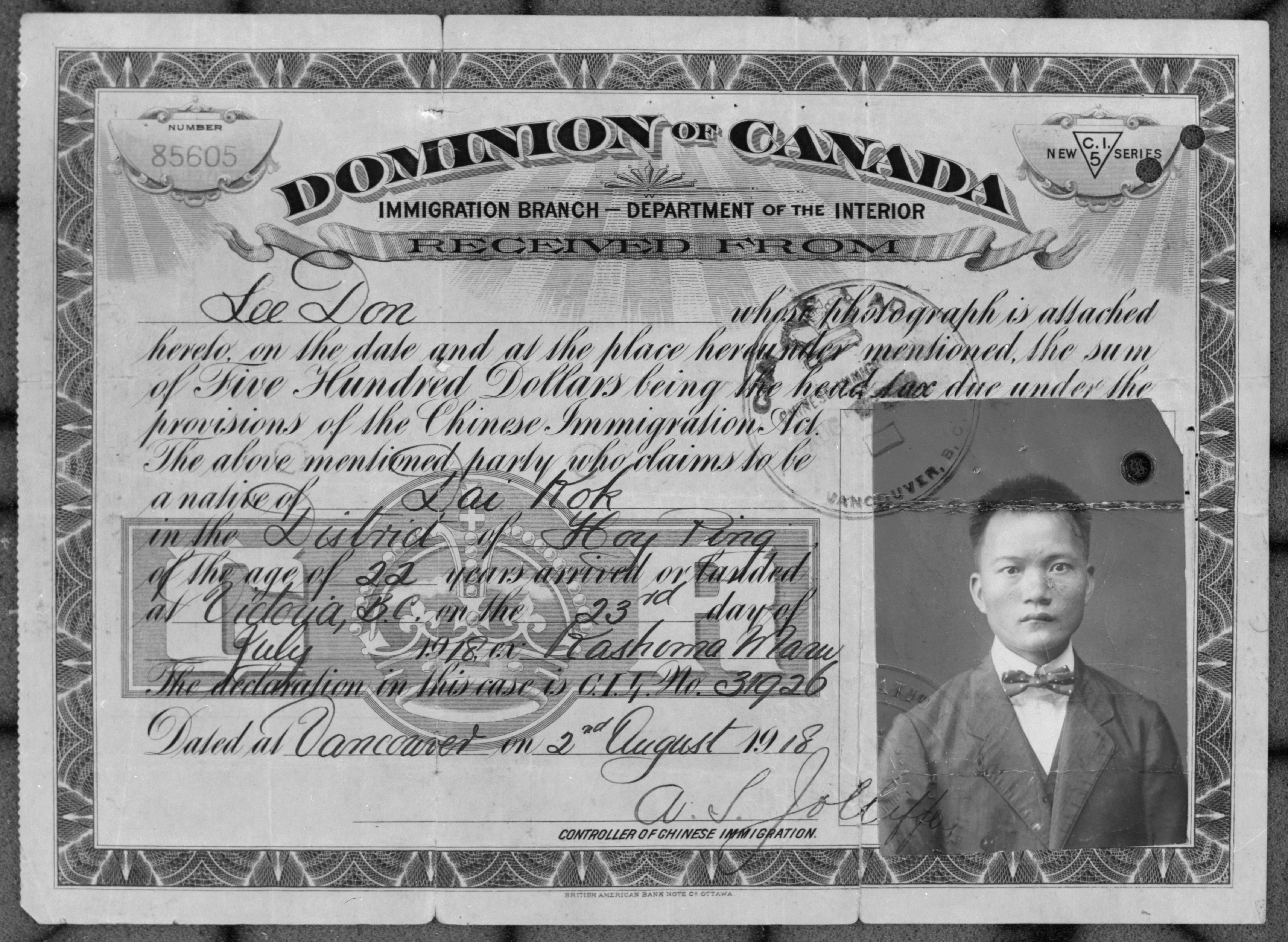

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Race relations between the Canadian state and the racial minorities living in the country may have come far since the Chinese head tax, but those relations remain an everyday struggle in the criminal justice system. The SCC's analysis of detention in the context of this case provides numerous benefits for future Charter litigation. Recognition of a racialized minority person's reasonable perception of policing conduct is a huge leap for the detention analysis. Now, the reasonable person will be one with an understanding of race relations of such communities with the police with the inherent increase in likelihood that a such a person would view themselves as being detained more readily than someone else. Further, the court's analysis moves the needle in terms of "when" detention occurs. Most prior cases place the "moment" of detention at the point where a person complies with a police demand, but here the Court found that point crossed when police entered the backyard and started asking questions. In other words, the accused had done nothing yet, but the Court found them to be detained. This makes good logical sense as the test for detention is modified objective and so is not dependent on the individual accused's actual perception of their situation. On the 24(2) side of the spectrum, the SCC has adopted the ONCA formulation that where both the first and second ground under Grant suggest exclusion, the third will rarely if ever support inclusion of the evidence on balance.

Pertinent Facts

"One evening, three police officers noticed four Black men and one Asian man in the backyard of a townhouse at a Toronto housing co-operative. The young men appeared to be doing nothing wrong. They were just talking. The backyard was small and was enclosed by a waist-high fence. Without a warrant, or consent, or any warning to the young men, two officers entered the backyard and immediately questioned the young men about “what was going on, who they were, and whether any of them lived there” (2014 ONSC 2033, at para. 17 (CanLII) (“TJR”)). They also required the young men to produce documentary proof of their identities. Meanwhile, the third officer patrolled the perimeter of the property, stepped over the fence and yelled at one young man to keep his hands where the officer could see them. Another officer issued the same order." (Para 1)

"The officer questioning the appellant, Tom Le, demanded that he produce identification. Mr. Le responded that he did not have any with him. The officer then asked him what was in the satchel he was carrying. At that point, Mr. Le fled, was pursued and arrested, and found to be in possession of a firearm, drugs and cash." (Para 2)

Police relied on some information to attend at the backyard: "... security guards...volunteered two pieces of information. First, that an unrelated individual, J.J., had been seen at the back of the L.D. townhouse days or weeks earlier (A.R., vol. III, at p. 16). Secondly, that the L.D. townhouse was, in one of the security guard’s opinion, a “problem address”, because “there were concerns of drug trafficking in the rear yard” (TJR, at para. 11)." (Para 8)

"That is, all officers understood the backyard was private property that was part of a private residence and was not public property or a common area to the co-op." (Para 9)

"Nonetheless, without warning by way of gesture or communication to the backyard occupants, Csts. Reid and Teatero simply entered the backyard through the opening in the fence. Cst. Teatero asked them “what was going on, who they were, and whether any of them lived there”. Cst. Reid engaged in a similar line of questioning. Each of the young men were asked to produce identification. This common police practice of asking individuals who they are and demanding proof of their identities for no apparent reason has its own name. It is known as “carding” (Justice M. H. Tulloch, Report of the Independent Street Checks Review (2018), at p. xi)." (Para 10)

"Rather than follow Csts. Reid and Teatero into the backyard, Cst. O’Toole initially patrolled the length of the fence to get a “better angle and better view of everybody”. He testified that a few moments later he stepped over the fence to enter the backyard."

Detention

"Specifically, in Grant, this Court held that a psychological detention by the police, such as the one claimed in this case, can arise in two ways: (1) the claimant is “legally required to comply with a direction or demand” (para. 30) by the police (i.e. by due process of law); or (2) a claimant is not under a legal obligation to comply with a direction or demand, “but a reasonable person in the subject’s position would feel so obligated” (para. 30) and would “conclude that he or she was not free to go” (para. 31)." (Para 25)

"Even, therefore, absent a legal obligation to comply with a police demand or direction, and even absent physical restraint by the state, a detention exists in situations where a reasonable person in the accused’s shoes would feel obligated to comply with a police direction or demand and that they are not free to leave. Most citizens, after all, will not precisely know the limits of police authority and may, depending on the circumstances, perceive even a routine interaction with the police as demanding a sense of obligation to comply with every request." (Para 26)

"A detention requires “significant physical or psychological restraint” (R. v. Mann, 2004 SCC 52 (CanLII), [2004] 3 S.C.R. 59, at para. 19; Grant, at para. 26; R. v. Suberu, 2009 SCC 33 (CanLII), [2009] 2 S.C.R. 460, at para. 3). Even where a person under investigation for criminal activity is questioned, that person is not necessarily detained (R. v. MacMillan, 2013 ONCA 109 (CanLII), 114 O.R. (3d) 506, at para. 36; Suberu, at para. 23; Mann, at para. 19). While “[m]any [police-citizen encounters] are relatively innocuous, . . . involving nothing more than passing conversation[,] [s]uch exchanges [may] become more invasive . . . when consent and conversation are replaced by coercion and interrogation” (Penney et al., at pp. 84-85)." (Para 27)

"The sometimes murky line between general questioning (which does not trigger a detention — see Suberu) and a particular, focussed line of questioning (which does) led this Court in Grant to adopt three non-exhaustive factors that can aid in the analysis. These factors are to be assessed in light of “all the circumstances of the particular situation, including the conduct of the police” (Grant, at para. 31):

(a) The circumstances giving rise to the encounter as they would reasonably be perceived by the individual: whether the police were providing general assistance; maintaining general order; making general inquiries regarding a particular occurrence; or, singling out the individual for focused investigation.

(b) The nature of the police conduct, including the language used; the use of physical contact; the place where the interaction occurred; the presence of others; and the duration of the encounter.

(c) The particular characteristics or circumstances of the individual where relevant, including age; physical stature; minority status; level of sophistication. [Emphasis added; para. 44.]" (Para 31)

Circumstances Giving Rise to the Encounter as They Would Reasonably Be Perceived

"Not only did three police officers enter a small private backyard in which five young men were standing around, talking, and “appeared to be doing nothing wrong”, the officers immediately questioned the young men about “what was going on, who they were, and whether any of them lived there”. They also required the young men to produce documentary proof of their identities and gave instructions about where to place their hands. It is common ground that the police had no legal authority to force the young men to do these things and the young men were under no legal duty to comply." (Para 34)

"The trial judge found (at para. 23) that the police officers had two specific investigative purposes: (1) the officers were investigating whether any of the young men were J.J. (or knew the whereabouts of N.D.-J.) and (2) the officers were investigating whether any of the young men were trespassers. The trial judge would later note (at para. 70) that the police were pursuing a third investigative purpose as well: the L.D. townhouse was a “problem address” in relation to suspected drug trafficking." (Para 36)

"The subjective purposes of the police are less relevant in this analysis because a reasonable person in the shoes of the putative detainee would not have known why these police officers were entering the property." (Para 37)

"Thus, the determination of the timing of the detention is not advanced by repeating that the police officers had “legitimate investigatory purposes”, “valid investigatory objectives”, “legitimate investigative aims”, “valid investigatory purposes” and were conducting a “legitimate investigation”... The legitimacy of any investigation in the context of s. 9 is measured against whether these objectives give rise to reasonable suspicion or not. We conclude that they did not and that the detention was therefore arbitrary." (Para 38)

"In such a situation, a reasonable person would know only that three police officers entered a private residence without a warrant, consent, or warning. The police immediately started questioning the young men about who they were and what they were doing — pointed and precise questions, which would have made it clear to any reasonable observer that the men themselves were the objects of police attention (R. v. Wong, 2015 ONCA 657 (CanLII), 127 O.R. (3d) 321, at paras. 45-46; R. v. Koczab, 2013 MBCA 43 (CanLII), 294 Man. R. (2d) 24, at paras. 90-104, per Monnin J.A. (dissenting), adopted in 2014 SCC 9 (CanLII), [2014] 1 S.C.R. 138). Further, the police demanded their identification and issued instructions, which would have made it clear to a reasonable observer that the police were taking control over the individuals in the backyard.:" (Para 40)

Nature of the Police Conduct

"A distinctive feature of the police conduct in this case was that the police were themselves trespassing in the backyard. This bears on the question of whether the detention occurred before the officer asked Mr. Le what was in his satchel. Other considerations that influence the analysis include: the actions of the police and the language used; the use of physical contact; the place where the interaction occurred and the mode of entry; the presence of others; and the duration of the encounter." (Para 43)

"The judicially constructed reasonable person must be taken to know the law and, as such, must be taken to know that the police were trespassing when they entered the backyard. (Para 44)

"The language used may show that the police are immediately taking control of a situation through loud stern voices, curt commands, and clear orders about required conduct. However, the power dynamic needed to ground a detention may be established without any of that." (Para 45)

"There is no evidence the police made any physical contact with the young men. There was, however, physical proximity: once the officers entered the backyard, there were eight people in a small space. Each of the officers positioned themselves in a way to question specific young men apart from the others. Lauwers J.A. observed that the officers positioned themselves in a manner to block the exit. This type of deliberate physical proximity within a small space creates an atmosphere that would lead a reasonable person to conclude that the police were taking control and that it was impossible to leave." (Para 50)

"The nature of any police intrusion into a home or backyard is reasonably experienced as more forceful, coercive and threatening than when similar state action occurs in public. People rightly expect to be left alone by the state in their private spaces. In addition, there is the practical reality that, when authorities take control of a private space, like a backyard or a residence, there is often no alternative place to retreat from further forced intrusion." (Para 51)

"In the circumstances of this appeal, to where, precisely, was Mr. Le expected to “walk away”? And from what was he being “delayed” when he was socializing at a friend’s house? In our view, such considerations have limited, if any, relevance when applied to police conduct at a private residence." (Para 52)

"The mode of entry would be seen as coercive and intimidating by a reasonable person. Two officers came in immediately. The fact that a third officer first walked the perimeter before entering over the fence would convey to a reasonable person that there was a tactical element to the encounter.... such tactics by the police to enter a private residence communicates an exercise of power and would be so understood by a reasonable person." (Para 56)

"While our colleague prefers to characterize the jump over the fence as a likely outcome of convenience, it is not clear how the convenience to the police has any impact about how it is perceived by a reasonable person. We are of the view that the entry over the fence conveyed a show of force." (Para 57)

"Living in a less affluent neighbourhood in no way detracts from the fact that a person’s residence, regardless of its appearance or its location, is a private and protected place." (Para 59)

"The trial judge noted that this neighbourhood of Toronto experiences a high rate of violent crime. The officers themselves testified to routinely patrolling this housing co-operative. But, the reputation of a particular community or the frequency of police contact with its residents does not in any way license police to enter a private residence more readily or intrusively than they would in a community with higher fences or lower rates of crime. Indeed, that a neighbourhood is policed more heavily imparts a responsibility on police officers to be vigilant in respecting the privacy, dignity and equality of its residents who already feel the presence and scrutiny of the state more keenly than their more affluent counterparts in other areas of the city (Canadian Muslim Lawyers Association’s factum, at p. 9)." (Para 60)

"In this case, the presence of others would likely increase, not decrease, a reasonable person’s perception that they were being detained. Each man witnessed what was happening to them all." (Para 63)

"The police did not tell any of the young men in the backyard that they were free to go and/or were not required to answer their interrogatories. What Mr. Le saw occurring to others likely increased the perception and reality of coercion." (Para 64)

"As to the duration of the encounter, although the interaction lasted less than a minute, the impact of the police conduct in that short space of time would lead any reasonable person to conclude that it was necessary to comply with police directions and commands..." (Para 65)

"In some cases, the overall duration of an encounter may contribute to the conclusion that a detention has occurred (i.e. the simple passage of time demonstrates how the person came to believe they could not leave). In other cases, however, a detention, even a psychological one, can occur within a matter of seconds, depending on the circumstances." (Para 66)

Particular Characteristics or Circumstances of the Accused

"Evidence about race relations relevant to the detention analysis, like all evidence of social context, can be derived from “social fact” or the taking of judicial notice. The information necessary to inform the reasonable person can take the form of reliable research and reports that are not the subject of reasonable dispute; and, rarely, direct, testimonial evidence. In this appeal, other than noting that he took a “realistic appraisal of the entire transaction” (para. 89), the trial judge did not consider the reasonable person in his analysis. This led to further error in the courts below in the assessment of Mr. Le’s level of sophistication and his subjective perceptions of the unfolding events." (Para 71)

"Binnie J. in Grant found that “visible minorities who may, because of their background and experience, feel especially unable to disregard police directions, and feel that assertion of their right to walk away will itself be taken as evasive” (paras. 154-55 and 169 (per Binnie J., concurring);" (Para 72)

"various groups of people may have their own history with law enforcement and that this experience and knowledge could bear on whether and when a detention has reasonably occurred....and such may impact upon their reasonable perceptions of whether and when they are being detained." (Para 73)

"racial profiling is anchored to an internal mental process that is held by a person in authority — in this case, the police. This means that racial profiling is primarily relevant under s. 9 when addressing whether the detention was arbitrary because a detention based on racial profiling is one that is, by definition, not based on reasonable suspicion. Racial profiling is also relevant under s. 24(2) when assessing whether the police conduct was so serious and lacking in good faith that admitting the evidence at hand under s. 24(2) would bring the administration of justice into disrepute." (Para 78)

"A reasonable person in the shoes of the accused is deemed to know about how relevant race relations would affect an interaction between police officers and four Black men and one Asian man in the backyard of a townhouse at a Toronto housing co-operative." (Para 82)

"In most cases, the knowledge imputed to the reasonable person comes into evidence as a social fact of which the judge may take judicial notice. In R. v. Find, 2001 SCC 32 (CanLII), [2001] 1 S.C.R. 863, McLachlin C.J. held that a court may “take judicial notice of facts that are either: (1) so notorious or generally accepted as not to be the subject of debate among reasonable persons; or (2) capable of immediate and accurate demonstration by resort to readily accessible sources of indisputable accuracy” (para. 48). These two criteria are often referred to as the Morgan criteria (see E. M. Morgan, “Judicial Notice” (1944), 57 Harv. L. Rev. 269)." (Para 84)

"To use Binnie J.’s test and terminology in Spence in this case: What would reasonable people, who have taken the trouble to inform themselves on the topic of race relations between the police and various racialized communities, know about the type of interaction that occurred in the backyard? What facts would be accepted as not being the subject of reasonable dispute?" (Para 88)

"Members of racial minorities have disproportionate levels of contact with the police and the criminal justice system in Canada (R. T. Fitzgerald and P. J. Carrington, “Disproportionate Minority Contact in Canada: Police and Visible Minority Youth” (2011) 53 Can. J. Crimin. & Crim. Just. 449, at p. 450)." (Para 90)

"Overall, the OHRC expressed serious concerns. The study revealed that “Black people are much more likely to have force used against them by the TPS that results in serious injury or death” and between 2013 and 2017, a Black person in Toronto was nearly 20 times more likely than a White person to be involved in a police shooting that resulted in civilian death (p. 19). The OHRC report reveals recurring themes: a lack of legal basis for police stopping, questioning or detaining Black people in the first place; inappropriate or unjustified searches during encounters; and unnecessary charges or arrests (pp. 21, 26 and 37)." (Para 93)

"The impact of the over-policing of racial minorities and the carding of individuals within those communities without any reasonable suspicion of criminal activity is more than an inconvenience. Carding takes a toll on a person’s physical and mental health. It impacts their ability to pursue employment and education opportunities (Tulloch Report, at p. 42). Such a practice contributes to the continuing social exclusion of racial minorities, encourages a loss of trust in the fairness of our criminal justice system, and perpetuates criminalization." (Para 95)

"A striking feature of these reports is how the conclusions and recommendations are so similar to studies done 10, 20, or even 30 years ago. These reports do not establish any new fact, but they build upon prior studies, research and reports and present a clear and comprehensive picture of what is currently occurring. Courts generally benefit from the most up to date and accurate information and, on a go-forward basis, these reports will clearly form part of the social context when determining whether there has been an arbitrary detention contrary to the Charter." (Para 96)

"We do not hesitate to find that, even without these most recent reports, we have arrived at a place where the research now shows disproportionate policing of racialized and low-income communities.... The documented history of the relations between police and racialized communities would have had an impact on the perceptions of a reasonable person in the shoes of the accused. When three officers entered a small, private backyard, without warrant, consent, or warning, late at night, to ask questions of five racialized young men in a Toronto housing co-operative, these young men would have felt compelled to remain, answer and comply." (Para 97)

"We stress that direct, testimonial evidence is usually not necessary to inform the reasonable person analysis. But, where appropriate, direct, testimonial evidence may be elicited." (Para 98)

"In the absence of testimonial evidence, which is what happens when such is either rejected or was never tendered, there is still a need to inquire into how the race of the accused may have impacted the s. 9 analysis.... The need to consider the race relations context arises even in cases where there is no testimony from the accused or any witness about their personal experience with police. Even without direct evidence, the race of the accused remains a relevant consideration under Grant." (Para 106)

"in our view, it is more reasonable to anticipate that frequency of police encounters will typically foster more, not less, “psychological compulsion, in the form of a reasonable perception of suspension of freedom of choice” (Therens, at p. 644). Individuals who are frequently exposed to forced interactions with the police more readily submit to police demands in order to move on with their daily lives because of a sense of “learned helplessness”" (Para 109)

"In our respectful view, the courts below erred when they gave priority to Mr. Le’s personal view that at one point in time he felt free to leave the backyard and try to enter the house. This transformed the detention analysis from an objective into a subjective inquiry." (Para 111)

"Before this Court, the Crown has argued that claimants’ subjective perceptions about whether or not they were detained are “highly relevant”. We do not accept this argument. It remains, and should remain, that the detention analysis is principally objective in nature. Prior to Grant, the objective nature of the test may have been unclear." (Para 114)

"a reasonable person would in our view conclude that there was a detention from the moment the officers entered the backyard and started asking questions." (Para 121)

"In these circumstances, we have no doubt that a reasonable mature adult would likely have concluded that there was no freedom to leave as soon as the police entered the backyard in the manner in which they did. In the same vein, a reasonable 20-year-old would even more readily conclude that he was detained in such circumstances. Indeed, his relative lack of maturity means the power imbalance and knowledge gap between citizen and state is even more pronounced, evident and acute." (Para 122)

"a person of small stature may be more likely to feel overpowered and conclude that it is not possible to leave the backyard. Such a person may think it more necessary to comply with the police commands and directions. This element, then, supports a conclusion that a detention arose at the moment the police entered the backyard." (Para 123)

Section 9 - Arbitrary Detention

"This Court’s decision in Grant provides guidance (at paras. 54-56), drawing from the three-part test stated in R. v. Collins, 1987 CanLII 84 (SCC), [1987] 1 S.C.R. 265, for assessing unreasonable searches and seizures under s. 8. Specifically, the detention must be authorized by law; the authorizing law itself must not be arbitrary; and, the manner in which the detention is carried out must be reasonable. In our view, the detention of Mr. Le was not authorized by law, and was, therefore, arbitrary." (Para 124)

The Police Were Trespassers

"Simply put, the implied licence doctrine does not apply to excuse the police presence in the backyard because even if “communication” was the officers’ purpose, it did not necessitate their entry onto private property — they could easily have spoken with the young men over the “little two-foot fence”." (Para 126)

"More fundamentally, in entering the backyard, the police also had what Sopinka J. in Evans referred to as a “subsidiary purpose”, which exceeds the authorizing limits of the implied licence doctrine (para. 16). In Evans, the subsidiary purpose that vitiated any “implied licence” was the hope of securing evidence against the home’s occupants (by sniffing for marijuana). Here, the subsidiary purpose was, in our view, correctly identified by Lauwers J.A. (at para. 107): “the police entry was no better than a speculative criminal investigation, or a ‘fishing expedition’”." (Para 127)

No Legal Authority to Detain

"No statute authorized these police officers to detain anyone in the backyard. At trial, the police invoked the Trespass to Property Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. T.21, as a source of authorization to enter to assess whether the young men were trespassing. However, as a matter of law, the Act does not authorize the police to engage in investigative detentions on private property. Rather, it provides authorization only for the police to arrest individuals where there are reasonable and probable grounds to believe that they are trespassing (s. 9). No such grounds existed." (Para 130)

"Similarly, the common law power to detain for investigative purposes could not have been invoked. This power allows the police to detain an individual for investigative purposes where, in the totality of circumstances, there are reasonable grounds to suspect a clear nexus between the individual and a recent or still unfolding crime (Mann, at paras. 34 and 45). Here, no such grounds existed." (Para 131)

"As this Court said in Mann, a suspect’s presence in a “so-called high crime area” is not by itself a basis for detention (para. 47).... As the Court of Appeal of Alberta said in R. v. O.(N.), 2009 ABCA 75 (CanLII), 2 Alta. L.R. (5th) 72 (at para. 40):

...As Iacobucci J. stated in Mann, the high crime nature of a neighbourhood, alone, is not enough. Even though some apartment buildings in a neighbourhood may be known to the police as havens of drug activity, that does not mean that anyone who enters any apartment building in an ill-defined area or neighbourhood can objectively be suspected of criminal activity. [Emphasis added.]" (Para 132)

"Investigative objectives that are not grounded in reasonable suspicion do not support the lawfulness of a detention, and cannot therefore be viewed as legitimate in the context of a s. 9 claim. This detention, therefore, infringed Mr. Le’s s. 9 Charter right." (Para 133)

Section 24(2) Analysis

"Where the state seeks to benefit from the evidentiary fruits of Charter offending conduct, our focus must be directed not to the impact of state misconduct upon the criminal trial, but upon the administration of justice.... What courts are mandated by s. 24(2) to consider is whether the admission of evidence risks doing further damage by diminishing the reputation of the administration of justice — such that, for example, reasonable members of Canadian society might wonder whether courts take individual rights and freedoms from police misconduct seriously.... our focus is on “the overall repute of the justice system, viewed in the long term” by a reasonable person, informed of all relevant circumstances and of the importance of Charter rights." (Para 140)

"In Grant, the Court identified three lines of inquiry guiding the consideration of whether the admission of evidence tainted by a Charter breach would bring the administration of justice into disrepute: (1) the seriousness of the Charter-infringing conduct; (2) the impact of the breach on the Charter-protected interests of the accused; and (3) society’s interest in the adjudication of the case on its merits.... It is the sum, and not the average, of those first two lines of inquiry that determines the pull towards exclusion." (Para 141)

"The third line of inquiry becomes particularly important where one, but not both, of the first two inquiries pull towards the exclusion of the evidence. Where the first and second inquiries, taken together, make a strong case for exclusion, the third inquiry will seldom if ever tip the balance in favour of admissibility (Paterson, at para. 56)." (Para 142)

Seriousness of the Charter-Infringing Conduct

"Further, as this Court held in R. v. Buhay, 2003 SCC 30 (CanLII), [2003] 1 S.C.R. 631, at para. 59, and Paterson, at para. 44, a “good faith” error on the part of the police must be reasonable and is not demonstrated by pointing to mere negligence in meeting Charter standards.... courts should dissociate themselves from evidence obtained as a result of police negligence in meeting Charter standards." (Para 143)

"It is, of course, open to a trial judge to determine that, even though something like racial profiling may often happen, it did not actually happen on the particular facts of an individual case." (Para 146)

"But an absence of bad faith does not equate to a positive finding of good faith and the officers were not acting in “good faith” simply because they were not engaged in racial profiling. Rather, for state misconduct to be excused as a “good faith” (and, therefore, minor) infringement of Charter rights, the state must show that the police “conducted themselves in [a] manner . . . consistent with what they subjectively, reasonably, and non-negligently believe[d] to be the law” (R. v. Washington, 2007 BCCA 540(CanLII), 248 B.C.A.C. 65, at para. 78)." (Para 147)

"So understood, good faith cannot be ascribed to these police officers’ conduct. Their own evidence makes clear that they fully understood the limitations upon their ability to enter the backyard to investigate individuals." (Para 148)

"And, as this Court has previously cautioned, “[w]hile police are not expected to engage in judicial refection on conflicting precedents, they are rightly expected to know what the law is” (Grant, at para. 133)." (Para 149)

"We are compelled, then, to conclude that this Charter-infringing conduct weighs heavily in favour of a finding that admission of the resulting evidence would bring the administration of justice into disrepute." (Para 150)

Impact on the Charter-Protected Interests of the Accused

"The second Grant line of inquiry requires us to consider whether, from the standpoint of society’s interest in respect for Charter rights, admission of evidence tainted by a Charter breach would bring the administration of justice into disrepute." (Para 151)

"What interests, then, of Mr. Le are protected by s. 9 of the Charter? This question was answered by this Court in Grant, at para. 20: “[t]he purpose of s. 9, broadly put, is to protect individual liberty from unjustified state interference” (emphasis added).... Absent compelling state justification that bears the imprimatur of constitutionality by conforming to the principles of fundamental justice (Grant, at para. 19), Mr. Le, like any other member of Canadian society, is entitled to live his life free of police intrusion." (Para 152)

"It is, of course, true that the length of Mr. Le’s detention was brief. But it does not necessarily follow that the impact on his liberty was trivial (Grant, at para. 42). Even trivial or fleeting detentions “must be weighed against the absence of any reasonable basis for justification” (Mann, at para. 56 (emphasis in original))." (Para 155)

"As to the trial judge’s suggestion that the impact on Mr. Le’s Charter protected interests was minor because he did not provide any inculpatory statement and because the evidence was discoverable in any event, we agree with Lauwers J.A. that the firearm and drugs were not discoverable, absent a breach. Discovery required an unconstitutional detention... (Para 156)

" This serious breach, moreover, had a significant impact upon Mr. Le’s protected interest under s. 9 in his liberty from unjustified state interference. It is difficult to imagine, absent actual physical constraint, a greater impact upon the practical ability of Mr. Le — “[a] person in the . . . position [of having] every expectation of being left alone” (Harrison, at para. 31) — to make an informed choice between walking away or speaking to the police. This line of inquiry also strongly favours a finding that admission of the evidence in this case would bring the administration of justice into disrepute. " (Para 157)

Society’s Interest in Adjudication of the Case on its Merits

"An “adjudication on the merits”, in a rule of law state, presupposes an adjudication grounded in legality and respect for longstanding constitutional norms." (Para 158)

"On balance, this line of inquiry provides support for admitting the evidence." (Para 159)

Balancing

"In view of our application of the three Grant lines of inquiry to the facts of this appeal, and with great respect to the courts below, we do not find this to be a close call. The police crossed a bright line when, without permission or reasonable grounds, they entered into a private backyard whose occupants were “just talking” and “doing nothing wrong”. The police requested identification, told one of the occupants to keep his hands visible and asked pointed questions about who they were, where they lived, and what they were doing in the backyard. This is precisely the sort of police conduct that the Charter was intended to abolish. Admission of the fruits of that conduct would bring the administration of justice into disrepute. This Court has long recognized that, as a general principle, the end does not justify the means (R. v. Mack, 1988 CanLII 24 (SCC), [1988] 2 S.C.R. 903, at p. 961). The evidence must be excluded." (Para 160)

"However, those who feel this is the wrong result should understand that “[t]his unpalatable result is the direct product of the manner in which the police chose to conduct themselves” (McGuffie, at para. 83; Paterson, at para. 56) — and not of an indifference on the part of this Court towards violence, drugs, or community safety." (Para 164)

R v Sanderson (SKQB)

[May 10/19] Self Defence - Battered Spouse Syndrome - 2019 SKQB 130 [Mitchell, J.]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: In this decision, Justice Mitchell offers a fresh application of the Battered Spouse defence in an aggravated assault case. Helpfully to the defence, no psychological evidence was advanced. Also, the accused did not actually remember the moment she applied force to the complainant.

Pertinent Facts

"Early on December 24, 2017, Ms. Sanderson and Mr. Obey together with their children drove to Regina to purchase Christmas gifts. After they made their purchases, they started to drive back to Pasqua First Nation. On the return trip, they stopped in Balgonie at approximately 4:00 p.m. to buy some liquor in order to have something to drink while Mr. Obey and Ms. Sanderson wrapped Christmas gifts later that evening." (Para 13)

"They all arrived at House 127 at approximately 6:00 p.m. in the evening. They all began to drink shortly after arriving at the house." (Para 17)

"Some time after this, Mr. Obey and his cousin, Leland, left the house, and drove to Fort Qu'Appelle to purchase more alcohol. Ms. Sanderson testified that they returned with "a 26"." (Para 18)

"Later in the evening, they were again running low on alcohol, so Ms. Sanderson, along with Ms. Mariah Obey, persuaded a friend named Wendy, to drive them to Fort Qu'Appelle in her vehicle to purchase more liquor. Ms. Sanderson testified that she purchased another "mickey" in Fort Qu'Appelle, and the trio made a leisurely return trip to Pasqua First Nation." (Para 19)

"When they arrived back at House 127, Mr. Obey was angry and demanded to know where they were. He demanded to know why it had taken them so long to return. Ms. Sanderson testified that he called her a "slut", a "whore" and a "bitch". He accused her of being with another man. Her evidence was corroborated by Ms. Mariah Obey." (Para 20)

"At that time they were in the kitchen, along with the couple's youngest child. Mr. Obey and Ms. Sanderson were arguing and the baby started to cry. Ms. Obey took the child to one of the second floor bedrooms. She testified that she laid down with the infant to try and calm her down." (Para 21)

"She could hear Ms. Sanderson and Mr. Obey arguing loudly. Mr. Obey was shouting while Ms. Sanderson was trying to calm him down. She heard what sounded like furniture being shoved around downstairs, and then a "big bang". Mr. Obey was screaming and called Ms. Sanderson a "whore"." (Para 22)

"Ms. Obey testified that she was aware of the history of physical violence between the couple. She "barricaded" herself in the bedroom with the children and telephoned her mother because she feared that Mr. Obey would assault Ms. Sanderson. She asked her mother to call 911." (Para 23)

"Mr. Obey admitted that when Ms. Sanderson and the others returned from Fort Qu'Appelle, he was very angry about how much time it took them to purchase liquor. He testified that Ms. Sanderson was very intoxicated when she returned. The two of them continued to drink. Things began to escalate and then, he said "she stabbed me in the face and the back of the head". (Para 29)

"She was afraid Mr. Obey would beat her, as he often punched her. She tried to calm him down. Ms. Sanderson testified that both she and Mr. Obey were "highly intoxicated"." (Para 37)

"Ms. Sanderson recalled that a scuffle ensued and Mr. Obey tried to physically intimidate her. However, she "blanked out", and the next thing she knew, Mr. Obey was lying on the kitchen floor, bleeding. Ms. Sanderson was crying, asked what happened, to which Mr. Obey replied "you stabbed me". She was holding him in her arms when the police arrived." (Para 38)

"The only rational explanation for Mr. Obey's serious physical injuries is that Ms. Sanderson stabbed him with a "hot" knife, a knife used to heat cocaine. From the very beginning, Ms. Sanderson has maintained that she has no recollection of stabbing Mr. Obey. Based on the evidence in this case, however, there is no other plausible explanation for Mr. Obey's injuries. As a result, I am satisfied beyond a reasonable doubt that Ms. Sanderson's actions did, indeed, cause Mr. Obey's grievous injuries." (Para 4)

The court found Ms. Sanderson to be a candid witness (Para 65) and Mr. Obey to be deceitful (Para 73)

Battered Spouse Syndrome Defence

"Section 34(1) applies to all forms of self-defence. If there is an air of reality to self-defence, no offence is committed unless the Crown disproves at least one of the following: (1) the accused believes on reasonable grounds that force is being used or threatened against a person; (2) the act that constitutes the offence is committed for the purpose of defending or protecting against that use or threat of force; and (3) the act committed is reasonable in the circumstances. See: R v Barrett, 2019 SKCA 6 (CanLII) at para 26, 52 CR (7th) 244 [Barrett] and Levy at para 107." (Para 79)

"In order to assess the last element identified above – whether the act at issue is reasonable in the circumstances – Parliament directed a trier of fact to take into account the non-exclusive list of nine factors in s. 34(2). See: Levy at para 107. It is at this stage of the analysis that the battered spouse syndrome becomes most relevant." (Para 80)

"R v Lavallee, 1990 CanLII 95 (SCC), [1990] 1 SCR 852 [Lavallee] was the first time the Supreme Court of Canada considered the battered spouse syndrome defence. It was elaborated on in subsequent authorities, most notably R v Malott, 1998 CanLII 845 (SCC), [1998] 1 SCR 123. One of the more significant innovations to the self-defence analysis emerging from Lavallee was that there was no requirement the apprehended danger must be imminent. Rather imminence was only one factor to be considered when assessing whether an accused had a reasonable apprehension of danger, and a reasonable belief that she could not extricate herself otherwise than by maiming or killing the aggressor. See: R v Pétel, 1994 CanLII 133 (SCC), [1994] 1 SCR 3 (QL) at para 22." (Para 81)

"This, and other relevant considerations, are now codified in s. 34(2). As the Nova Scotia Court of Appeal elaborated in Levy, at para 112:

[112]…Importantly, an accused need not wait until he or she is actually assaulted before acting, and an accused is not by law required to retreat before acting in self-defence. The imminence of the threat, the existence of alternative means to respond, and the actions taken by the accused are factors that belong in the things a trier of fact is required to consider to determine if the act committed by the accused was reasonable in all of the circumstances; and an accused is not expected to weigh with nicety the force used in response to the perceived use or threat or force. [Emphasis added.]" (Para 82)

"Even if an accused's evidence is not accepted in its entirety, the court still must acquit if the totality of the evidence raises a reasonable doubt respecting his or her guilt. See: Ejigu at para 13." (Para 84)

Application of Principles to the Facts

"Even absent this concession by Crown counsel, I would have found an air of reality existed respecting the battered spouse defence. Ms. Sanderson testified at length about the history of physical and verbal abuse she experienced during her domestic relationship with Mr. Obey. I have already concluded that Ms. Sanderson was a credible witness, and for the most part a reliable one. I believed her testimony." (Para 87)

"I have already concluded that Ms. Sanderson did stab Mr. Obey with the hot knife. On the totality of the evidence relating to the second element of the offence, I am satisfied that she did so to protect herself from yet another physical assault from Mr. Obey. As a result, I find that the Crown has not displaced the operation of these two elements beyond a reasonable doubt." (Para 92)

Reasonableness Element

"In the course of her testimony, Ms. Sanderson identified at least four occasions when Mr. Obey's actions caused her to fear for her life." (Para 93)

- "Mr. Obey broke into the bathroom. Ms. Sanderson was going to call 911 but could not. They fought. Mr. Obey started choking her. Ms. Sanderson testified that she "crouched down", in an attempt to shield herself from being struck by Mr. Obey." (Para 95)

- "...three years ago. Mr. Obey had been drinking, an argument ensued and Mr. Obey strangled her until she blacked out." (Para 98)

- "Ms. Sanderson described as an "attempted suicide by car"....Mr. Obey was driving drunk. She stated that he was driving in an erratic and reckless manner. At one point, he swerved in front of an oncoming vehicle but managed to avoid a collision." (Para 99)

- During supper "He began to complain about the food. He told Ms. Sanderson: "I should just end you." Ms. Sanderson took that to mean he wanted to kill her." (Para 100)

During one incident, when she was 18, Obey kicked her in the stomach while she was pregnant (Para 104)

"There were other instances referenced during Ms. Sanderson's testimony. Suffice it say, the evidence I have recounted in the preceding paragraphs aptly and sufficiently describe circumstances which constitute a reliable basis for concluding her actions on December 24, 2017 were reasonable." (Para 114)

"Of particular relevance is the factor enumerated in s. 34(2)(e), namely the "size, age, gender and physical capabilities of the parties to the incident". Mr. Obey testified that he was approximately 6 feet, 2 1 / 2 inches tall and weighed about 230 pounds. Although Ms. Sanderson did not formally state her height or weight, I could plainly see that she was much shorter and weighed far less than 230 pounds. In other words, Mr. Obey was physically far more imposing than Ms. Sanderson." (Para 115)

"Finally, as further corroboration of the abusive nature of the couple's relationship, Mr. Obey admitted in his testimony that he had a criminal record, three of those conviction were convictions for assaulting Ms. Sanderson. Two of those convictions pre-dated the events of December 24, 2017." (Para 117)

"I accept that although she has no recollection of doing so, Ms. Sanderson did stab Mr. Obey late on Christmas Eve 2017 and caused his grievous injury. However, his verbal threats and physical intimidation gave her reason to fear for her safety, and in light of many years of physical abuse and assaults she had endured, her response of picking up a hot knife and stabbing Mr. Obey was reasonable in all of the circumstances." (Para 127)

R v Bartholomew (ONCA)

[May 7/19] – Witness Credibility - Absence of Motive to Fabricate – 2019 ONCA 377 [Reasons of Gary Trotter J.A., with David M. Paciocco J.A. and L.B. Roberts J.A. concurring]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: An absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. This aphorism remains true when applied to a complainant's lack of motive to fabricate an allegation of sexual assault. Trial judges can be reminded with this case that the absence of evidence to support a motive to fabricate does not entitle them to find the complainant had none. Particularly helpful for the defence is the commentary of the Court that evidence of a good relationship with he accused and evidence that police contacted the complainant (instead of the inverse) are facts that are incapable of establishing a lack of motive to fabricate.

Pertinent Facts

“The appellant was found guilty of one count of sexual assault and one count of sexual interference, contrary to ss. 271 and 151 of the Criminal Code, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-46. The trial judge entered a conviction for sexual interference, and conditionally stayed the sexual assault count." (Para 1)

"The complainant alleged a single incident of touching. He testified that it happened before a gym class. After changing into his athletic clothing, the complainant made his way from the change room to the gym via a space described at trial as a vestibule or short hallway. This is where he encountered the appellant. The complainant believed that he was the last student to leave the change room on the day of the incident." (Para 4)

"The appellant had his back to the door leading from the hallway to the gym, which would have prevented anyone from coming in from the gym. According to the complainant, the appellant asked him about his genital area, but the complainant could not remember exactly what the appellant said. The complainant stated that the appellant touched his penis under his shorts or pants for about five seconds. He was not sure whether it was also inside his underwear. The appellant said something reassuring afterwards, but the complainant could not remember exactly what was said." (Para 5)

"The trial judge accepted the complainant's evidence. She rejected the appellant's evidence. She was satisfied beyond a reasonable doubt that the incident described by the complainant happened. In reaching these conclusions, the trial judge relied on "evidence of an absence of motive" on the complainant's part to fabricate the allegation." (Para 7)

Complainant's Motive to Fabricate

"During closing submissions, defence counsel (not Mr. Burgess) acknowledged that the complainant appeared to harbour no bad feelings toward the appellant, such that revenge was an unlikely motive. However, she pointed out that there are "many reasons" why someone may fabricate an allegation, reasons that may never come to light. Asked by the trial judge to give some examples, defence counsel suggested financial gain. When asked if there was a financial motive in this case, defence counsel responded: "Well, I don't know Your Honour, which is really my point." When further challenged on the point, defence counsel submitted that "what you have here at most . . . is an absence of evidence of motive."" (Para 15)

"The Crown acknowledged that there was no onus on the appellant to establish a motive. However, he referred to the defence submission that there was merely an absence of evidence of motive and said, "[t]hat's not what we have here", suggesting that a lack of motive was proven on the evidence. He submitted that it was a "very, very important fact to consider when examining the credibility of a witness"." (Para 16)

"The trial judge agreed with the Crown's approach. She twice mentioned in her reasons for judgment that the complainant had no motive to fabricate the allegation. When first addressing the issue, the trial judge said:

The defence has no onus to point to a motive to fabricate. The onus in a criminal prosecution always rests upon the Crown. However, at the same time, an absence of motive can be relevant in assessing the credibility of a witness. In this regard, I find the evidence of both witnesses indicate that the nature of the relationship was such that M.K. [the complainant] did not have a motive, either back in 2002-2003 or in 2016-2017 to make up this allegation against [the appellant]. In addition, as noted earlier, M.K. did not go to the police, they called him.

I find there is evidence of an absence of motive which is relevant in assessing M.K.'s credibility." (Para 17)

"Later in her reasons, the trial judge addressed the question of motive again:

While it is very important to remember that there is no onus on the defence to establish a motive, the defence did make submissions about M.K. having a possible monetary motive and that there are many reasons people lie. A money motive was never put to M.K. in cross-examination.

The absence of any evidence of a financial motive to lie is therefore noted in the context of this defence submission and should be considered in relation to the earlier remarks in this decision in relation to motive. [Emphasis added.] (Para 18)

"I agree with the appellant that the trial judge erred by transforming the absence of evidence of a motive to fabricate into a proven lack of motive, contrary to this court's decision in R. v. L.L., 2009 ONCA 413, 96 O.R. (3d) 412." (Para 19)

"However, problems occur when the evidence is unclear – where there is no apparent motive to fabricate, but the evidence falls short of actually proving absence of motive. In these circumstances, it is dangerous and impermissible to move from an apparent lack of motive to the conclusion that the complainant must be telling the truth. People may accuse others of committing a crime for reasons that may never be known, or for no reason at all: see R. v. J.V., 2015 ONCJ 815 (CanLII), at para. 132; R. v. Sanchez, 2017 ONCA 994 (CanLII), at para. 25; L.L., at para. 53; R. v. T.G., 2018 ONSC 3847 (CanLII), at para. 30; R. v. Lynch, 2017 ONSC 1198 (CanLII), at paras. 11-12." (Para 22)

"Therefore, in this context too, there is a “significant difference” between absence of proved motive and proved absence of motive: L.L., at para. 44, fn. 3. The reasons are clear. In R. v. B. (R.W.) (1993), 24 B.C.A.C. 1 (C.A.), Rowles J.A. explained, at para. 28: “it does not logically follow that because there is no apparent reason for a motive to lie, the witness must be telling the truth.” This point was made in L.L., in which Simmons J.A. said, at para. 44: “the fact that a complainant has no apparent motive to fabricate does not mean that the complainant has no motive to fabricate” (emphasis added). See also R. v. O.M., 2014 ONCA 503 (CanLII), 313 C.C.C. (3d) 5, at paras. 104-109; and R. v. John, 2017 ONCA 622 (CanLII), 350 C.C.C. (3d) 397, at para. 93." (Para 23)

"More importantly, evidence of a good relationship between the complainant and the appellant was not capable of proving that the complainant had no motive to fabricate; it could do no more than support the conclusion of an absence of evidence of a proved motive: White, at p. 608; L.L., at para. 45; John, at para. 94. This state of affairs was not capable of enhancing the complainant’s credibility, as the trial judge did. At best, it was a neutral factor." (Para 25)

"Moreover, the trial judge's reliance on the fact that the complainant was contacted by the police (instead of the opposite) was misplaced. The Crown elicited this information at the end of the complainant's examination-in-chief. The issue was not pursued by defence counsel, for good reason. The evidence was prejudicial, suggesting that "where there's smoke there's fire". It should not have been admitted. Moreover, it does not necessarily follow that being contacted by the police is inconsistent with a motive to fabricate. It certainly does not constitute evidence capable of establishing a lack of motive." (Para 27)

"In conclusion, I am satisfied that the trial judge's findings on the issue of motive formed an important part of her credibility assessment of the complainant. She used her finding of a proved absence of motive to enhance the credibility of the complainant, which was a central issue at trial. This amounted to a miscarriage of justice warranting a new trial." (Para 28)