This week’s top three summaries: R v Chouhan, 2020 ONCA 40, R v CEK, 2019 ABCA 2, and R v Roberts, 2019 SKPC 72.

R v Chouhan (ONCA)

[Jan 23/20] Charter s.11(d)/(f), 7 - Peremptory Challenge Amendment Constitutionality & Retrospectivity - 2020 ONCA 40 [Reasons by Watt J.A., with Doherty, and Tulloch JJ.A. concurring]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: The Ontario Court of Appeal has weighed into the amendments to the jury system from Bill C-75 that came into effect in September 19, 2019. In one fell swoop, the Court has declared the death of the peremptory challenge constitutional along with the replacement of triers with the judge on a challenge for cause. In one slight ray of sunshine, the Court has declared that the change to peremptory challenges applies prospectively. The question in Ontario seems settled for the moment. Likely, most of the country will follow suit.

Peremptory challenges are not the saviour many defence lawyers believe. Simply put, it has been a numbers game. If your goal has been to increase visible minority representation on your jury, this tool is not a good one. By definition there are fewer visible minorities than the Caucasian population in most jury pools. Since the Crown has the same amount of peremptory challenges, all they need to do is exercise it once or twice to have an all white jury. Defence counsel can burn through all of them and not reach even one person of colour.

The SCC is unlikely to disagree with the general propositions posited by Justice Watt. Counsel should stop being reactionary in respect of these changes to the code and instead look for opportunities in the case law for positive change. I'll try to identify some below.

Bottom Line

[4] I decide that neither the abolition of peremptory challenges nor the substitution of the trial judge for lay triers to determine the truth of the challenge for cause is constitutionally flawed.

[5] With respect to the temporal application of the amendments, I decide that the abolition of the peremptory challenge applies prospectively, that is to say, only to cases where the accused’s right to a trial by judge and jury vested on or after September 19, 2019. But I conclude the amendment making the presiding judge the trier of all challenges for cause applies retrospectively, that is to say, to all cases tried on or after September 19, 2019, irrespective of when the right vested.

Peremptory Challenges - The Argument and Ruling on 11(d)

[61] Section 11(d) includes the right be tried by an impartial jury: R. v. Williams, [1998] 1 S.C.R. 1128, at para. 48.

[62] To determine whether a tribunal is impartial, the question is whether a reasonable person, fully informed of the circumstances, would have a reasonable apprehension of bias: Kokopenace, at para. 49; Bain, at pp. 101, 111-12 and 147-48. The informed person begins their analysis with a strong presumption of juror impartiality and a firm understanding of the numerous safeguards in the jury selection process designed to weed out potentially biased candidates and to ensure that selected jurors will judge the case impartially. The reasonable apprehension of bias has never hinged on the existence of a jury roll or, for that matter, a jury that proportionally represents the various groups in our society: Kokopenace, at para. 53; Find, at paras. 26, 41-42 and 107; Williams, at para. 47.

[63] The test for impartiality includes a twofold objective component. First, the observer. The person considering the alleged bias must be reasonable. The observer must be informed of the relevant facts and view the matter realistically and practically. The reasonable observer does not depend on the views or conclusions of the accused: R. v. S. (R.D.), [1997] 3 S.C.R. 484, at para. 111, per Cory J.; R. v. Dowholis, 2016 ONCA 801, 341 C.C.C. (3d) 443, at para. 20. Second, the apprehension of bias. That too must be reasonable in the circumstances of the case: S. (R.D.), at para. 111, per Cory J.

Application

[88] ....The limited number of peremptory challenges and their exercise based on inherently subjective considerations make them structurally incapable of solving for real or perceived racial bias, let alone necessary to secure the right to a fair hearing and impartial tribunal.

[89] To the contrary, once a real risk of partiality has been established, the next step must be to identify and exclude all jurors who are partial. In the abstract, whatever mechanism is used to identify partiality must be applied to (or, at minimum, be capable of being applied to) every potential juror. This is because the risk of prejudice that the appellant identifies is a general one. It is a concern about the jury pool as a whole and is not limited to specific jurors. If every potential juror may be prejudiced or partial, then the “filter” for partiality must apply to all potential jurors. The peremptory challenge, by its very nature, cannot fill this role.

Peremptory Challenges - The Challenge under 11(f)

[106] An accused’s right to the benefit of a trial by jury does not extend to proportionate representation at any stage of the jury selection process: neither the process followed to compile the jury panel roll nor the in-court process to select the jury to try the issues on the indictment: Kokopenace, at paras. 70-71. See also R. v. Biddle, [1995] 1 S.C.R. 761, at paras. 56-58, per McLachlin J. (concurring).

Application

[108] First, the core of this dispute involves the impact of the abolition of peremptory challenges on the impartiality of the jury selected to try the case and the fairness of the trial. These are interests guaranteed more particularly by s. 11(d) of the Charter. In the absence of any infringement of s. 11(d), there can be no infringement of the right to a trial by jury as guaranteed by s. 11(f).

[109] Second, although the role of representativeness is broader under s. 11(f) than under s. 11(d), the obligation imposed on the state remains the same. And that obligation relates to the process used to compile the jury roll, not the in-court selection process or the composition of the trial jury.

Substitution of Judge as Trier in Challenge for Cause

[151] First, the test for independence and impartiality of a tribunal is the same: whether a reasonable person, fully informed of the circumstances, viewing the matter realistically and practically and having thought the matter through, would conclude that the decision-maker is not likely to decide the issue fairly: Kokopenace, at para. 49; Valente v. the Queen, [1985] 2 S.C.R. 673, at p. 689; S. (R.D.), at para. 111, per Cory J.

[155] First, the substitution of the presiding judge as the arbiter of the truth of the challenge for cause does not compromise the independence of the jury. The standard the judge applies in determining the question of impartiality which frames the challenge is identical to that applied by lay triers. Like lay triers, the judge benefits from a strong presumption of impartiality. And, as in the case of lay triers, the presumption is only rebutted by cogent evidence. The subjective beliefs of an accused that a judge is tethered to the state is not evidence. Indeed, the practice as it has developed since September 19, 2019, albeit not statutorily mandated, is to permit the parties to make submissions about each prospective juror’s impartiality. This procedure was not followed with lay triers, whether rotating or static. [Emphasis added] [159] Finally, the assignment of the presiding judge to the role of trier of the truth of the challenge for cause does not compromise the traditional division of responsibilities between judge and jury in a criminal trial. Parliament has always assigned a role in decisions about challenges for cause to the presiding judge. For example, to determine whether a juror’s name was on the panel. Or what to do if lay triers were unable to make a decision within a reasonable time on a challenge for cause. Or choosing lay triers. And instructing the lay triers. This is not a usurpation of a role assigned to others.

The Enhanced Judicial Stand Aside Power

[Part of the argument advanced by the Appellant was this:] [38] ... Similarly, while the challenge for cause is a tool to root out potentially racist jurors, it is a coarse filter. Its “yes” or “no” answers to the questions and rejection of demeanour as a determinant allow some prospective jurors with racist beliefs to slip through the cracks. And while the presiding judge has the power to excuse and stand by potential jurors, these powers are not linked to issues of potential bias or prejudice and are exercised by the judge without participation by the accused or their counsel. The expanded stand by ground – “maintaining public confidence in the administration of justice” – adds nothing to the former authority.

[However, the Court said this:]

[70] This stand by authority is available after a prospective juror has been called under s. 631(3) or (3.1), and thus is available before or after a challenge for cause has been heard and its truth determined. The language of “personal hardship” and “any other reasonable cause” duplicates that in the excusal authority of s. 632(c). But the language “maintaining public confidence in the administration of justice” is new and, as a matter of statutory construction, covers different ground. In this case, for example, the trial judge used it to direct a prospective juror, who had been found impartial on the challenge for cause, to stand by. The basis for its exercise was the appellant’s belief, communicated to the trial judge through counsel, that a rude gesture had been made by the prospective juror when asked to face the appellant.

[71] We did not receive any submissions that would permit me to mark out the boundaries of this additional authority. Suffice it to say that its presence is of further assistance in ensuring the constitutional requirement – an impartial jury.

[So, here is where counsel should get creative. The ONCA has provided an open door to the systemic problem of all-white juries presiding over trials with visibility minority accused. It can be argued that public confidence in the administration of justice today includes some element of visible representation of a visible minority's race. I acknowledge the Court's comments at para 74 to the contrary, but those comments may simply be the residual effect of insufficient evidence on the issue of differential results and previous judicial hesitation to accept the evidence that does exist]

The Temporal Application of the Amendments

Peremptory Challenges

[211] In short, the amendment eliminating peremptory challenges applies prospectively, that is to say, only to cases where the accused’s right to a trial by judge and jury vested on or after September 19, 2019. Stated otherwise, if, prior to September 19, 2019, an accused had a vested right to a trial by judge and jury as it existed in the prior legislation, then the amendment does not apply and both the accused and Crown have the right to peremptory challenges, even if the trial is held after that date.

[212] To be clear, not all accused charged with an offence before September 19, 2019 have a vested right to a trial by judge and jury under the former legislation. For the right to have vested, the accused must have, before September 19, 2019: (i) been charged with an offence within the exclusive jurisdiction of the Superior Court; (ii) been directly indicted; or (iii) elected for a trial in Superior Court by judge and jury. I include in the third category accused who have formally entered an election as well as those who have made a clear, but informal election, as evinced by the transcript of proceedings or endorsements on the information. Otherwise, the accused’s right did not vest, the amendment applies, and no party has a right to peremptory challenges at the trial.

Judge as Trier of Challenge for Cause

[215] The essential difference between the former and current provisions is twofold. The identity of the trier. And the availability of a choice of trial procedure (rotating versus static triers). Unlike the abolition of peremptory challenges, however, the challenge for cause procedure remains available with the same threshold for access, burden of proof, standard of proof and consequence if successful. The change effected by the amendment does not impair or negatively affect the right to trial by judge and jury as it existed prior to the amendment.

[216] In the result, I am satisfied that the amendment to the challenge for cause procedure is purely procedural, thus applies to both past and future events, irrespective of whether the accused had a vested right before September 19, 2019 to a trial by judge and jury under the former legislation.

R v CEK (ABCA)

[January 7/20] Appeals - Misapprehension of Evidence applied to Credibility - 2020 ABCA 2 [Frans Slatter J.A., Barbara Lea Veldhuis J.A., Jo'Anne Strekaf J.A.]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Getting the facts right is important. Where the trial record shows that a trial judge misapprehended factual evidence that was then used to undermine the credibility of an accused, a new trial is almost certainly assured.

Pertinent Facts

[3] The appellant and the complainant cohabited between October 2009 and June 2011, along with the complainant’s four children. The complainant testified that after a few months of a “fairly normal” sexual relationship, things changed. She testified that the appellant told her that he had sex with his sister when they were teenagers after they got off the school bus, and that the appellant’s mother confirmed to her that this had happened. The complainant testified that, after this disclosure, she was regularly subjected to sexual abuse by the appellant without her consent, including forced penile vaginal intercourse, forced fellatio, vaginal penetration with objects, four instances of forced anal intercourse, being choked to unconsciousness during sex on several occasions, constant requests that she urinate in his mouth (which she sometimes complied or attempted to comply with), and being urinated upon by him without warning when she was using the toilet.

[4] The complainant also testified that, beginning in January of 2011, the appellant tied her to the bed on several occasions while she was asleep, and she would awaken to him sexually assaulting her. She said there were two bolts at the head and two bolts at the foot of the bed and ropes ran through rings that had been slid through the bolts.

[5] The complainant told the appellant to leave in June 2011, which he did. She testified that in the summer of 2011 a friend helped her remove the bolts, and dismantle and burn the bed. Two bolts from the bed were entered as exhibits at trial; the complainant said these had come from the headboard. The complainant’s friend testified about the removal of the bolts and the dismantling of the bed. He said that this occurred in the spring of 2014, not in 2011, that the bolts entered as exhibits looked like the bolts from the foot of the bed, but that there were no bolts in the headboard, just holes. He was fairly certain about the timing because he moved out of a condo in Vegreville in the spring of 2014 and back into his camper for the summer, and no longer needed his bed.

[7] The appellant also testified at trial. He denied that any nonconsensual sexual activity occurred, or that they engaged in any sexual activities involving choking, anal intercourse, ropes, penetration with objects or urination. He stated that, after separation, he and the complainant had an acrimonious property dispute, that the complainant sent him angry and threatening text messages and that they both agreed to a no contact agreement. He denied having sex with his sister, or telling the complainant that he had. The appellant’s mother denied that she told the complainant that the appellant had sex with his sister. She also testified that the complainant made remarks to her about framing men. Both the appellant’s mother and his wife testified that they had seen threatening text messages that were apparently from the complainant.

Misapprehension of Evidence - the Law

[10] The standard of review to set aside a conviction on appeal due to a misapprehension of evidence by the trial judge is stringent. “The misapprehension of the evidence must go to the substance rather than to the detail. It must be material rather than peripheral to the reasoning of the trial judge…the error thus identified must play an essential part not just in the narrative of the judgment but ‘in the reasoning process resulting in a conviction’”:R v Lohrer,2004 SCC 80 at para 2.

[11] Guidance is provided in R v Morrisey (1995), 1995 CanLII 3498 (ON CA), 22 OR (3d) 514 (CA):

....Where a trial judge is mistaken as to the substance of material parts of the evidence and those errors play an essential part in the reasoning process resulting in a conviction then, in my view, the accused's conviction is not based exclusively on the evidence and is not a "true" verdict.... If an appellant can demonstrate that the conviction depends on a misapprehension of the evidence then, in my view, it must follow that the appellant has not received a fair trial, and was the victim of a miscarriage of justice. This is so even if the evidence, as actually adduced at trial, was capable of supporting a conviction.

[12] The importance of credibility findings being based on the correct version of the evidence was recognized in Whitehouse v Reimer, 1980 ABCA 214 at paras 8 – 9:

Where a principal issue on a trial is credibility of witnesses to the extent that the evidence of one party is accepted to the virtual exclusion of the evidence of the other, it is essential that the findings be based on a correct version of the actual evidence. Wrong findings on what the evidence is destroy the basis of findings of credibility.It is not to the point in our view to say that the incorrect version is only slightly different than the actual evidence. Where the trial Judge perceives that a witness is lying because of that small difference, and is in error in that perception, there must be a risk that his perception of all the remaining evidence is coloured.

Application to the Facts

[13] It is not disputed that the trial judge made a misstatement regarding the evidence about the removal of the bolts. It will be recalled that the complainant testified that the bed was dismantled in the summer of 2011, when bolts were removed from the head and from the foot of the bed. She said that the bolts entered as an exhibit at trial were from the head of the bed, and that she was unable to locate the bolts removed from the foot. The testimony of the complainant’s friend was that the bolts were removed in the spring of 2014, not in the summer of 2011. He also said that at that time there were bolts in the foot of the bed, but not in the headboard, where there were only holes.

[14] The trial judge mischaracterized this evidence, stating that the friend, like the complainant, described removing the bolts in the summer of 2011...

[15] ....the trial judge considered the friend’s evidence important in that it supported the evidence of the complainant. Her reliance on the evidence of the friend, and the importance of his testimony with respect to timing, is also apparent...

[16] Similarly, in dismissing an application for a mistrial brought by the appellant, the trial judge stated that she “specifically relied on the presence of the bolt as I assessed [the complainant’s] credibility. [The friend’s] observation (and participation in the removal) of the bolt on the bed was striking and added weight to her evidence”: R v C.E.K., 2018 ABQB 579 at para 30.

[26] The trial judge also erroneously characterized as irrelevant other aspects of the evidence of defence witnesses. She found that evidence from the appellant’s wife and mother describing texts, allegedly sent by the complainant, threatening to “ruin” the appellant’s life, was not relevant. An accused who denies that alleged events occurred may attempt to identify a motive for fabrication, and evidence to that effect may be highly relevant. With respect specifically to the evidence of the appellant’s wife that she was shown a text allegedly from the complainant that said “I will ruin your life”, the trial judge made no finding as to whether the text had been sent. She concluded, “whether or not it was in fact sent by the complainant, is not helpful to my assessment of credibility and the truthfulness of her allegations”. The trial judge appears to have lost focus of the significance of this evidence. Since motivation to fabricate was a relevant issue, whether such texts were sent by the complainant was a relevant fact on which the trial judge failed to make a finding.

[27] We are satisfied that the trial judge’s misapprehension of the friend’s evidence of when the bolts were removed, and its inconsistency with that of the complainant, was a matter of substance and not simply detail. The evidence was material to the trial judge’s reasoning and played an essential part of her assessment of the complainant’s credibility. Further, this misapprehension may have coloured the trial judge’s perception of the evidence as a whole. There is a real risk of a miscarriage of justice.

- new trial was ordered

R v Roberts (SKPC)

[December 13/19] – Charter s.8 - Confidential Informant Information Leading Search - Strip Search Violation - Charter s.10(b) Violation by not allowing Call before Strip Search – 2019 SKPC 72 [H.M. Harradence J.]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Herein, Judge Harradence provides a thorough analysis of what is required to conduct a drug search on the highway and then a more intrusive strip search. The case serves as a good example of what happens when tunnel vision obscures the decisions of investigators. Tunnel vision becomes clear when officers rely on the lack of evidence to support alleged reasonable grounds for a search. Here, after the failure to find any drugs or drug related property during the initial search, the investigator used this information to order a strip search.

Pertinent Facts

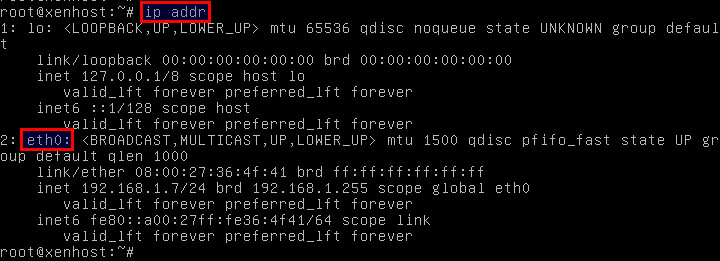

[1] On May 24, 2017, a vehicle driven by Nicole Daigneault (Daigneault) was stopped by Cst. Ogieglo and Cst. Walker. There was one passenger, Karrie Roberts (Roberts). After the stop the two females were immediately arrested. The stop and the arrest were at the direction of Cpl. Knodel (Knodel). He had confidential information from Sgt. Dunn, indicating that there was cocaine in the vehicle. [2] No cocaine was found in the vehicle. Daigneault and Roberts were taken to the Waskesiu RCMP detachment. Knodel made the decision that both females should be strip searched. In the process of the strip search, Roberts surrendered a package containing 28 grams of cocaine. Roberts and Daigneault were transported to the Hospital in Prince Albert where further searches, including x-rays, were performed by medical personnel to determine whether any further cocaine was in the body of either female. None was found. [7] Knodel testified that in the spring of 2017 he was involved in an investigation into drugs and gangs in La Ronge. This investigation included a number of officers from La Ronge and Prince Albert. Grant McKenzie was a target of this investigation. McKenzie was believed to be a member of the Kings street gang in La Ronge. His girlfriend was Daigneault. (P-1 – excerpt of Lucille target book.) She was known to drive a black 4-door Grand Prix. [9] On May 24, 2017, as a result of information he received from Sgt. Dunn, Knodel believed he had grounds to arrest:[10] Mr. Slobodian, Crown counsel, asked Knodel to specify his grounds:Sergeant Dunn advised me that he had received confidential information that Nicole Daigneault was travelling from Prince Albert to La Ronge, she would be in possession of a large amount of cocaine, she would be riding with Grant McKenzie and she’d be driving a black, four-door car. (trial transcript pages 11-12)

[11] Knodel believed Grant McKenzie would be in the vehicle with Daigneault. He believed that McKenzie could be violent, and officers should use extreme caution in the vehicle stop. [12] Knodel gave the blanket direction to Cst. Ogieglo that all occupants of the vehicle were to be arrested. His belief was that the occupants of the vehicle, whether their identity was known or not would be involved in the drug trade:So just knowing the history of Nicole Daigneault and that she was a drug trafficker in La Ronge as well as what I observed on May 20th, several days before that, and what’s most importantly in the new information received from Sergeant Dunn that Nicole Daigneault was on her way back to La Ronge with cocaine and then that, of course, would be corroborated if we actually found her travelling from PA to La Ronge, which we did. (trial transcript page 12)

In my -- in my experience, anybody in that vehicle would have knowledge of the drug trafficking activities for her to drive 1 to Prince Albert and back to La Ronge. Any person -- and at that point I was expecting it to be Grant McKenzie, but my direction to them was to arrest anybody in that vehicle, because, in my experience, anybody who would have been in that vehicle would have knowledge and possibly be assisting her with the drug trafficking or the concealment of drugs. (trial transcript pages 12-13. See also page 33, lines 5 – 12.)

[16] Cst. Ogieglo testified that she arrested the passenger, Roberts. At that point neither Cst. Ogieglo nor any member of the investigative team, including Knodel, had any information about Roberts. The police did not know who she was.[19] At 9:33 p.m. Cst. Walker read Daigneault her Charter rights. She replied that she wished to call a private lawyer. Cst. Walker intended to allow her to make a call at the detachment, but at the scene he proceeded to question her about the contents of the vehicle and her purse. (trial transcript pages 96 – 98)

[20] No cocaine was found after a search of the vehicle or the two females. A cell phone, some white powder determined not to be cocaine by Walker and some cash was seized at the roadside. Both Daigneault and Roberts were taken to the Waskesiu Detachment. Knodel ordered a strip search be performed by Cst. Ogieglo. Knodel explained the basis for this search as follows:[21] The strip search was conducted by Cst. Ogieglo. Nothing was found when Daigneault was searched. Roberts produced a bag of cocaine from a body cavity prior to Cst. Ogieglo starting the search of her. It is agreed that this bag contained 28 grams of cocaine. (trial transcript pages 49 – 50) [22] As part of the strip search, Knodel made the decision to suspend the right to counsel of both Daigneault and Roberts. In cross-examination he explained that this decision was to prevent the destruction of evidence:So at that point I knew no drugs had been found, so in my experience and with what we knew about the confidential informant information I believed that it was reasonable and likely that those drugs were concealed in a body cavity in one of the two females that were arrested. Both those females were put into the cells and the water was turned off in order to prevent destruction of evidence. So one of the priorities when you arrest somebody is to give them opportunity to contact counsel as soon as possible. Unfortunately I couldn’t do that prior to a proper search, to prevent destruction of evidence, so at that point I spoke with Constable Ogieglo, who’s a female member out of Waskesiu/Montreal Lake. I asked her to do a private search of the two females and that I suspected they had drugs hidden in their body cavities…I had no information that the drugs were going to be hidden inside of a body cavity. I didn’t know that. That’s based -- that was based off of my experience and throughout the course of my career we’ve had several instances where drugs have been found in body cavities.

[24] Once the cocaine was seized, Knodel believes he directed both females be transported to hospital in Prince Albert for further medical procedures. He explained that he had a dual purpose for making this decision – the health and safety of the accused and to search for evidence...A That's correct, because, of course, as we all know, when you allow somebody to contact counsel they’re put in private -- in a private room, so it would be so easy just to -- if they have a bag of cocaine in their -- in their body cavity, they can take it out, open it up and throw it throughout the room or -- just distribute it throughout the room into the carpet and it would be gone. There would be no evidence left.

Confidential Source Information

[28] When the authority to arrest is challenged, the Crown must provide an evidentiary foundation. The seminal case involving source information is R v Debot, 1989 CanLII 13 (SCC), [1989] 2 SCR 1140 [Debot]. Justice Wilson illuminates three concerns which are to be assessed cumulatively in determining whether the Crown has satisfied the requirements of reasonable grounds:1.) was the information predicting the commission of a criminal offence compelling;2.) was the tip credible; and3.) was the information corroborated by police information prior to making the decision to search/arrest.

(R v Debot, at p 1168. See also R v Shinkewski, at p 22, R v Pavlik, 2019 SKCA 107, at para 22 [Pavlik] and R v Dawad, at para 46.)

Application

[32] There is significant detail which is missing from the information provided by Sgt. Dunn on May 24, 2017:While I appreciate the objective reasonableness requirement must be viewed in the light of the investigating officer’s background and experience, deference to an officer’s intuition must not render the objective element of the inquiry meaningless.

[35] There is some corroboration of the information provided by Sgt. Dunn on May 24, 2017. The black Grand Prix is headed north to La Ronge. Daigneault is driving the vehicle. On a significant point, the observations of the vehicle contradict the source information. Grant McKenzie is not in the vehicle. Unexpectedly, another female, Roberts, is in the vehicle. The police do not know Roberts.

[36] A review of the May 24 source information raises concerns. The information is brief and conclusory. The basis for the information, whether it is first or second-hand hearsay is unknown. The credibility and reliability of the source is unknown. The extent to which the source information is corroborated is limited and contradicted on a material point. When I consider the totality of the evidence adduced in this voir dire, in light of the three-pronged Debot test, I conclude that the source information falls short of compelling. The evidence does show a need for further investigation, but this evidence alone does not justify an immediate arrest of all of the occupants of the vehicle.[37] The stopping of the vehicle by Cst. Ogieglo and Cst. Walker was for the sole purpose of arresting the occupants. I find the warrantless arrest of Roberts and Daigneault to be unlawful and arbitrary within the meaning of s. 9 of the Charter. (R v Perello, 2005 SKCA 8, 257 Sask R 46, at paras 40 – 41.) For the foregoing reasons I find the arrest in this case was not lawful and therefore the searches cannot be justified by the arrest. (R v Smith, 2019 SKCA 126, at para 19; R v Fearon, 2014 SCC 77, 318 CCC (3d) 182, at para 27; and R v Mann, 2004 SCC 52, 185 CCC (3d) 308, at para 37.) I find the searches of Daigneault and Roberts were unreasonable and violated s. 8 of the Charter.The Decision to Strip Search

[38] As part of the searches, Cpl. Knodel directed Cst. Ogieglo strip search both females. Cst. Ogieglo performed the strip search in a method that respected the privacy of Roberts and Daigneault. The concern with these searches is the basis for them. As indicated in R v Golden, 2001 SCC 83, 159 CCC (3d) 449 [Golden] there must exist reasonable grounds to justify this type of search. Cpl. Knodel’s grounds for this search are concisely stated in his examination in-chief (see para 20 above).[39] At paragraph 71 of the Crown brief it is argued that the strip search is justified by the following four factors:It is submitted that the following factors are relevant in assessing whether there were sufficient grounds to justify the strip search conducted:- Cpl. Knodel’s extensive experience with investigations involving drugs being hidden or concealed, particularly in respect to those circumstances where a vehicle is being employed.

- A pat down search incidental to the arrest of the accused did not result in any drugs being found.

- Given the quantities expected, Cpl. Knodel directed members to search those areas of the vehicle most often used to conceal drugs at the scene of the vehicle stop. No drugs were discovered as a result of that search.

- Although no drugs were seized roadside, a cutting agent was discovered in the vehicle. Cpl. Knodel testified that this discovery was indicia of drug trafficking.

Section 10(b) Violations

[44] Of greater significance is Cpl. Knodel’s decision to suspend the right to counsel of both suspects until after the completion of the strip search. The suspension was brief – approximately 15 minutes....[45] Justice Barrington-Foote recognized the importance of the right to counsel being implemented without delay. This is particularly significant in this context where the police were preparing to strip search both individuals:[81] The s. 10(b) right is not the right to counsel. It is the right to counsel without delay. Time matters. That is so regardless of whether the accused is treated “respectfully” and whether any evidence is elicited before the right to counsel is implemented. In my view, this breach had a serious impact on the interests protected by s. 10(b). (R v Moyles, 2019 SKCA 72.)[46] Despite Cpl. Knodel’s evidence that “I always give lots of opportunity for the person to cooperate ahead of a strip search and that would be a last resort,” it appears that his decisions were motivated by a sense of urgency which is not justified by the circumstances. He arrived at the detachment at 10:45 p.m. and by 10:59 p.m. both strip searches were complete. (Trial transcript, at pages 9 and 29.) I am unable to accept his explanation that he delayed providing Daigneault and Roberts with an opportunity to contact counsel in order to prevent the destruction of evidence. I reach this conclusion particularly in light of the evidence of Cst. Ogieglo regarding the observation window in the door of the telephone room. I have concluded that this delay resulted in a violation of the accused’s s. 10(b) rights.

Section 24(2) Analysis

Seriousness of the Charter Infringing State Conduct

[50] Cpl. Knodel’s actions demonstrates tunnel vision and a willful blindness regarding the rights of the two female suspects. His evidence demonstrated to me a focus on arresting and searching these individuals rather than a willingness to consider all incriminating and exonerating evidence. (Shinkewski, at para 13(c).)[52] In this case I have found that the police violated multiple rights of the accused. The seriousness of these infringements is compounded by the Crown’s failure to call Sgt. Dunn (R v Pavlik, at para 63):[53] In these circumstances I assess the seriousness of the state conduct as high. It is clear to me that Cpl. Knodel had the experience and training to recognize the shortcomings of the source information; however, he was blinded by his desire to make an arrest and seizure.While I agree the arresting officers in this case were entitled to rely on another officer’s assessment of the tipster’s credibility, the Court is not so entitled. An individual’s Charter right to be free from arbitrary detention and the Court’s role under our Constitution require that the Court must have the opportunity to critically evaluate the objective reasonableness of the state’s grounds for arrest without a warrant. As Wilson J. made clear in R v Debot, the Crown may overcome frailties in the evidence supporting an informant’s credibility with evidence of a compelling tip and corroboration of the tip, but the credibility of the tipster nonetheless remains relevant and material to the overall assessment of the grounds for arrest. It will not be necessary to call the police officer who handled the tip in every case; however, the failure to do so in this case isolated the claim of tipster credibility from the Court’s review, thereby rendering null one of the three questions in R v Debot. While there may have been legitimate reasons for this circumstance (e.g., concerns about maintaining informant confidentiality, etc.), the Crown has not made them known to the Court.

The Impact of the Violations on the Accused

[54] Roberts was unknown to the police before May 24, 2017. Daigneault was known as the girlfriend of McKenzie, an alleged violent drug dealer. Both were treated the same: arrested, suspension of rights to counsel, searched, strip searched and then transported to hospital where further searches were performed, including x-rays. No other conclusion can be reached than the effect of the breaches for both Daigneault and Roberts was significant. In Golden, at para 89, Justices Iacobucci and Arbour recognized the acute interference with privacy resulting from a strip search:The importance of preventing unjustified searches before they occur is particularly acute in the context of strip searches, which involve a significant and very direct interference with personal privacy. Furthermore, strip searches can be humiliating, embarrassing and degrading for those who are subject to them, and any post facto remedies for unjustified strip searches cannot erase the arrestee’s experience of being strip searched. Thus, the need to prevent unjustified searches before they occur is more acute in the case of strip searches than it is in the context of less intrusive personal searches, such as pat or frisk searches.