This week’s top three summaries: R v Cooper, 2020 BCCA 206, R v West, 2020 ONCA 473, and R v E.B., 2020 ONSC 4383

R v Cooper, 2020 BCCA 206

[July 20, 2020] Party Liability under s.21(2) - Foreseeability that act WILL occur not MIGHT occur is required [Reasons by Madam Justice Bennett with Mr. Justice Goepel and Madam Justice Griffin Concurring]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Party liability is the mucky back door of criminal law. When Crown prosecutors use it, they leave their boots on and track the dirt all through a well-prepared defence case. Ultimately, it can be difficult to defend all the angles, so clarity is a welcome relief whenever you can find it in appellate jurisprudence. Otherwise, try to remember to lock that back door.

Where an accused is alleged to have been part of a plan to commit one offence and another occurred, they can be held to be a party if they ought to have know it was a probable consequence of carrying out the plan to commit the first offence. In this assessment, it in sufficient that the consequence "might" occur. Such a standard would open culpability up to an almost infinite variety of other offences committed by the other members of the plan.

Overview

[1] Malcolm Cooper and three others committed crimes in the course of what is colloquially known as a “home invasion.”

[2] Several firearms were found at the scene, and shots had been fired from one of them. Although the trial judge concluded that a co-accused had fired those shots and that Mr. Cooper did not have possession of any of the guns, he convicted Mr. Cooper as a party to three firearms offences. Mr. Cooper appeals those convictions on the basis that the judge erred in his analysis of party liability. He does not appeal his other convictions stemming from the home invasion.

Facts of the Home Invasion

[8] John Morrison was beaten by the intruders and has no memory of the home invasion.

[9] Ms. Moayed had been in her bedroom with her daughter. She heard noises and emerged to find three intruders beating John Morrison. A fourth intruder was standing off to the side.

[10] At some point later, all four intruders, John Morrison, Ms. Moayed and her daughter were together in a bedroom. During that time, one of the intruders fired a gun. Ms. Moayed testified that this individual had a short, stocky build. She provided physical descriptions of the other intruders as well.

[11] The police arrived shortly after the gun was fired. Three officers entered the front of the house and three went around the back. The police officers first encountered John Morrison, bloodied, near the front door. They subsequently found Ms. Moayed in her bedroom with her daughter and one of the intruders, John MacInnis. A second intruder, Tristan Wight, was located in another bedroom, where officers also discovered a second firearm. Mr. MacInnis and Mr. Wight were the only two intruders in the house.

[12] One of the police officers who had gone around the back of the house saw someone jump over a fence. Officers searched the area and eventually found and arrested the appellant, Mr. Cooper. They also located a Smith & Wesson pistol on the ground in the backyard. Mr. Cooper’s hands and face later tested positive for gunshot residue, but an expert testified that the residue could have been transferred.

[13] A fourth intruder, Mr. Marcos Cardoso, was arrested at a 7-Eleven store in the early morning hours of the next day. Among the four intruders, he was the only one who matched the description given by Ms. Moayed as to who shot the gun in her bedroom.

[14] Mr. Cardoso and Mr. Cooper were tried together. Mr. Wight and Mr. MacInnis both pleaded guilty and testified at Mr. Cooper’s trial.

Trial Ruling

[17] The judge found (at para. 150) that Mr. Cooper was “actively engaged” in the events in the bedroom, thus attracting liability for the firearms-related offences as a party. Citing s. 21(c) of the Criminal Code, (a provision that does not exist) he said this:

[204] I conclude, given the nature and objective of the home invasion, the retrieval of three handguns from the scene, the fact there were no other forms of restraint available to the accused, and that it was known to all participants that guns were going to be used prior to the entry in the residence and that it was objectively foreseeable to all in those same circumstances, (going into a home for a perceived million-dollar robbery), that resistance and that guns might be discharged by one or more of the intruders carrying such. [Emphasis by Author]

[18] The judge was not satisfied beyond a reasonable doubt that Mr. Cooper was in possession of the Smith & Wesson found in the backyard. He accordingly acquitted Mr. Cooper of Counts 9 and 10 relating to that weapon.

Party Liability

[26] Section 21(2) of the Criminal Code permits a court to find someone culpable of a crime when it is the foreseeable and probable consequence of a common intention to carry out an unlawful purpose:

knew or ought to have known was a probable consequence of carrying out an unlawful purpose in common with the actual perpetrator.”(2) Where two or more persons form an intention in common to carry out an unlawful purpose and to assist each other therein and any one of them, in carrying out the common purpose, commits an offence, each of them who knew or ought to have known that the commission of the offence would be a probable consequence of carrying out the common purpose is a party to that offence.

[27] Section 21(2) has three essential elements: (1) an agreement to participate in the unlawful purpose; (2) the commission of an incidental and different crime by another participant; and (3) knowledge, that is, foreseeability of the likelihood of the incidental crime being committed: see R. v. Cadeddu, 2013 ONCA 729 at para. 53; and R. v. Simon, 2010 ONCA 754 at para. 43.

[28] The unlawful purpose is different from the crime charged. In R. v. Simpson, 1988 CanLII 89 (SCC), [1988] 1 S.C.R. 3 at p. 11, Justice McIntyre, for the Court, noted “… a person may become a party to an offence [pursuant to s. 21(2)] committed by another which he knew or ought to have known was a probable consequence of carrying out an unlawful purpose in common with the actual perpetrator.”

Analysis of Party Liability

[31] The judge concluded that by being actively engaged in the primary offence, liability flowed for the incidental offence. Active engagement in the primary offence does not necessarily mean the elements for party liability are met for an incidental offence. Here, the trial judge failed to consider whether it was foreseeable that the firearms would be used or discharged as an incidental crime to the primary offence.

[32] In addition, when the judge later stated (at para. 204) that “all participants [knew] that guns were going to be used … and that it was objectively foreseeable … that resistance was foreseeable and that guns might be discharged” (emphasis added), he committed an error in law. The test, as noted above, is whether it was reasonably foreseeable that the incidental offences would occur, not whether they “might” occur.

Curative Proviso

[36] The evidence supporting actual knowledge by Mr. Cooper that the others carried weapons is not overwhelming. Furthermore, the evidence pointing to reasonable foreseeability that Mr. Cardoso would fire his weapon is not so overwhelming that it can be said that no wrong or substantial miscarriage of justice would result if the convictions are sustained. Therefore, I would not apply the curative proviso in these circumstances.

Conclusion

[37] Mr. Cooper says there must be a new trial, as there is evidence that may support a conviction if the proper test is applied. He does not seek an acquittal.

[38] I would allow the appeal, set aside the convictions for the firearms offences found in Counts 2, 4 and 8, and order a new trial for those offences.

R v West, 2020 ONCA 473

[July 22, 2020] Charter s.8 - Importance of Correct Standard on Prior Judicial Authorization Police Affidavit [Reasons by Tulloch J.A. with Watt, and Trotter JJ.A. concurring]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: What happens when the issuing justice and the affiant on the application for warrant or other prior judicial authorization get the standard wrong for the application they are doing? This happens when statutes change (here the standard for a production order changed) or when old statutes are applied to new technology. The case is useful for the analysis that would apply in those situations. Arguably, the finding that the affiant was negligent in not knowing the new standard would be different for a new technology case, but maybe not. One could argue that where the law is unclear, police ought to choose the standard that respects the right to privacy more and to do anything different is simply to negligently gamble on the rights of privacy of the target.

Pertinent Facts

[4] At some point between the dates of August 21, 2016 and September 19, 2016, an image of child pornography was uploaded as the profile picture for an account on Kik, an instant messaging application for mobile devices.

[5] The image was detected by Kik and reported to the National Child Exploitation Coordination Centre, which proceeded to notify the Hamilton Police Service. The report contained the following pertinent details: the image had been uploaded between August 21, 2016 and September 19, 2016; it had been uploaded to an account with the username “mikeandvikes”, which had been registered on August 14, 2016; the image had been uploaded by an Android device, a Samsung Model SM-T530NU; and the first and last Internet Protocol (“IP”) addresses to be associated with the use of the account were 24.141.35.79 (“79”), and 24.141.102.67 (“67”), respectively. The report also included disclaimers stating that the information it contained had not been verified by Kik.

[6] From the report, the police were able to determine that both IP addresses belonged to Cogeco Cable and that they were leased to users in Hamilton, Ontario. The police sent a preservation demand to Cogeco, requesting that it preserve any subscriber information associated with the two IP addresses. Cogeco agreed to do so with regards to the second IP address, 67, but noted that the records for the first IP address, 79, were no longer on file.

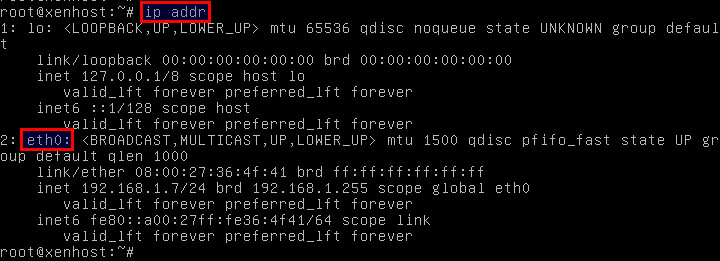

[7] Detective Constable Jeremy Miller, a police officer since 2002, drafted an Information to Obtain (“ITO”) for a general production order under s. 487.014 of the Criminal Code, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-46, which was granted on December 20, 2016. The affidavit appended to the ITO stated “that the information set out herein constitutes the grounds to suspect” that the subscriber(s) committed the offences of distribution and possession of child pornography, contrary to ss. 163.1(3) and 163.1(4) of the Criminal Code (emphasis added).

[8] Pursuant to the production order, Cogeco provided the subscriber information associated with the second IP address. The information revealed that the subscriber was Steve West, located at 46 Longwood Road, North, Hamilton. Further investigation confirmed that 46 Longwood was a residence, and that Steven Todd West was one of the owners.

[10] The search led to the seizure of digital devices and media, including a total of 19,687 files containing child pornography, and information showing that the appellant was the owner of the “mikeandvikes” Kik account. Of the files obtained, 10,804 were unique (i.e., not duplicates of other files). The files were found on five different devices: two laptop computers, two cell phones, and a USB drive.

Validity of the Production Order

[19] Section 487.014 of the Criminal Code provides the authority under which a valid production order can be issued. It reads as follows:

(1) Subject to sections 487.015 to 487.018, on ex parte application made by a peace officer or public officer, a justice or judge may order a person to produce a document that is a copy of a document that is in their possession or control when they receive the order, or to prepare and produce a document containing data that is in their possession or control at that time. ...

Conditions for making order

(2) Before making the order, the justice or judge must be satisfied by information on oath in Form 5.004 that there are reasonable grounds to believe that

[20] Recently, in R. v. Vice Media Canada Inc., 2017 ONCA 231, 137 O.R. (3d) 263, aff’d 2018 SCC 53, [2018] 3 S.C.R. 374, Doherty J.A. outlined the general principles governing the issuance of production orders. He stated, at para. 28:

A production order under s. 487.014 of the Criminal Code is a means by which the police can obtain documents, including electronic documents, from individuals who are not under investigation. The section empowers the justice or judge to make a production order if satisfied, by the information placed before her, that there are reasonable grounds to believethat: (i) an offence has been or will be committed; (ii) the document or data is in the person’s possession or control; and (iii) it will afford evidence of the commission of the named offence. If those three conditions exist, the justice or judge can exercise her discretion in favour of granting the production order. [Emphasis added.]

[21] In the case at bar, the affiant, Detective Constable Miller, swore the following in the affidavit to obtain the production order:

I believe that the information set out herein constitutes the grounds to suspect that Cogeco Cable subscriber(s) with the internet protocol (IP) addresses of …[Emphasis added.]

[22] Detective Constable Miller misstated the standard another four times throughout his affidavit. He never asserted that he had evidence to satisfy the actual standard for the issuance of the production order – reasonable grounds to believe. Despite this clear flaw, the issuing justice authorized the production order.

[23] The error was also missed by the trial judge. In fact, the trial judge’s conclusion for upholding the production order tracked the wording of the affiant, asserting that the ITO presented sufficient information to “establish a reasonable suspicion permitting the issuance of the production order.” Beyond this clear error, the trial judge’s reasons were also otherwise inadequate, as they provided no substantive analysis. The trial judge thus failed to properly carry out his role of determining whether the issuing justice could have concluded that the statutory threshold was met: R. v. McNeill, 2020 ONCA 313, at para. 30.

[25] In my view, it was an error for the issuing justice to issue the order, given that the officer never subjectively asserted that he had the grounds necessary to satisfy the statutory requirements: R. v. Storrey, 1990 CanLII 125 (SCC), [1990] 1 S.C.R. 241, at pp. 250-251. There is no way to reasonably read the ITO and come away with any conclusion other than that there were reasonable grounds to suspect that an offence had been committed, that the information sought was in a person’s control, and that the information would afford evidence of the commission of the offence. This is insufficient to permit the issuance of a production order.

[28] In reviewing the ITO, it is clear that the warrant could not have been issued as, without the subscriber records, the police would not have been aware that the appellant was associated with the second IP address. Without this information, the police would not have been able to provide a location for the search or any details regarding the specific target. Under these circumstances, the statutory requirements under s. 487(1) could not have been met, as there would be no “building, receptacle or place” to search. The search of the appellant’s home and electronic devices was therefore unlawful and a violation of the Charter: Spencer, at para. 74.

Section 24(2) Analysis

[32] The first line of inquiry considers the seriousness of the Charter infringing conduct and whether it rises to a level of severity such that the courts should dissociate themselves from the conduct by excluding any evidence it produced: Grant, at para. 72; R. v. Thompson, 2020 ONCA 264, 62 C.R. (7th) 286, at para. 83. The courts should dissociate themselves from evidence obtained through a negligent breach of the Charter: R. v. Le, 2019 SCC 34, at para. 143.

[33] In this case, Detective Constable Miller was negligent in failing to apply the correct legal standard in his affidavit. The standard of reasonable grounds to believe, as outlined in s. 487.014 of the Criminal Code came into force on March 9, 2015: Bill C-13, An Act to amend the Criminal Code, the Canada Evidence Act, the Competition Act and the Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Act, 2nd Sess., 41st Parl., 2013-2014 (assented to 9 December 2014). The production order in this case was signed on December 20, 2016, more than a year after the amendments took effect. By this time, the requisite legal standard was well established and Detective Constable Miller should have been aware of this. This factor militates in favour of exclusion.

[35] In this case, the impact on the accused’s interests was serious. The police searched the appellant’s subscriber information, his home, and his electronic devices. All of these areas attract a heightened expectation of privacy: Spencer, at paras. 66, 78; R. v. Adler, 2020 ONCA 246, 62 C.R. (7th) 254, at para. 33, citing R. v. Silveira, 1995 CanLII 89 (SCC), [1995] 2 S.C.R. 297, at para. 140, and R. v. Morelli, 2010 SCC 8, [2010] 1 S.C.R. 253, at para. 2.

[36] The Crown, however, takes the position that, despite the error in the affidavit, the information available to the police, including the information contained in the Kik report, provided reasonable grounds to believe that a crime had been committed, that Cogeco had control of certain subscriber information, and that, that information would afford evidence of the commission of the crime. While this argument was put forward by the Crown on the first ground of appeal, it effectively amounts to an argument that the impact of the breach was lessened in light of the fact that the evidence was “discoverable”, as the police had the requisite grounds to obtain the production order and, by extension, the search warrant.

[37] I do not accept this argument.

[38] ... Put differently, the only information the police had was that an unknown person, using an unknown device, had accessed the account from the 67 IP address on September 19, 2016.

[39] This was not a sufficient evidentiary basis to provide a “credibly-based probability” that the production of the subscriber information would afford evidence of the commission of the offence: McNeill, at para. 32. More was needed to establish a connection between the alleged offence and the subscriber information sought. Additional evidence was particularly important in this case, as it was not clear whether the IP address information provided could be relied upon, as the report stated that the IP address information collected “isn’t verified by Kik.” In his expert testimony, Martin Musters explained that further investigative techniques were available to the police, including requesting the precise IP address associated with the upload of the image, and inquiring as to the IP address associated with the email address used to register the account. These steps were readily available and may well have narrowed the focus of the investigation. In the absence of any evidence beyond the unconfirmed information that the Kik account had been accessed using a particular Internet account, the police were effectively fishing for a connection to the offence. The appellant’s subscriber information was thus not discoverable and the impact of the unlawful search on his Charter-protected interests was not diminished. This factor favours exclusion.

[41] The final stage of the analysis under s. 24(2) involves balancing the factors under the three lines of inquiry to determine whether the admission of the evidence would bring the administration of justice into disrepute. While this balancing is not a mathematical exercise, where the first two inquiries militate in favour of exclusion, the third inquiry “will seldom, if ever, tip the balance in favour of admissibility”: R. v. Harrison, 2009 SCC 34, [2009] 2 S.C.R. 494, at para. 36; R. v. McSweeney, 2020 ONCA 2, 384 C.C.C. (3d) 265, at para. 81; Thompson, at paras. 106-107.

[42] In this case, the first and second lines of inquiry provide a strong case for exclusion. The state conduct was negligent and it had a serious impact on the appellant’s Charter rights. While this is a case where exclusion will gut the Crown’s case, this result is appropriate. Admission of the evidence would bring the administration of justice into disrepute.

[43] For these reasons, the evidence obtained pursuant to both the production order and search warrant should be excluded under s. 24(2) of the Charter.

Conclusion

[44] In all the circumstances, I would allow the appeal and enter acquittals on all counts.

R v E.B., 2020 ONSC 4383

[July 17, 2020] – Bail and Section 493.2 - Indigenous Peoples, Racially Marginalized Groups, and the Mentally Ill - New Principles of Bail Applied - Evidence At the Bail Hearing [P.A. Schreck J.]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Over the last five years, the SCC has been reinforcing the expected normalcy of prior judicial interim release. People should be getting bail on the least strict conditions possible. The judgements represent a significant change from past process and a significant effort at standardisation across the country. In this decision, Justice Schreck puts much of this jurisprudence together. Particularly, the Zora decision and s.493.2. These are used to undermine the predictive value of breaches on the secondary and tertiary ground concerns. This fundamental shift allows defence lawyers to now advance bail plans for people with records that may be blighted by systemic discrimination within the justice system. On older principles, these individuals would not have been eligible for release, but with this new law in mind, their release should be encouraged to counterbalance past and current systemic discrimination and ensure the proper functioning of the justice system. People at the bail stage are presumed innocent and the law has shifted to give this actual effect for those who were most disadvantaged over years of justice system neglect and refusals to acknowledge that often, our system is part of the problem.

This case also advances an important caveat to the admissibility of evidence at a bail hearing. Normally, documents are admissible if they are credible and trustworthy. This case introduces a procedural step akin to Brown v Dunn on the Crown. If the Crown is going to undermine a surety with documents, they must at least present those documents to the cross-examined surety to give them a chance to answer. Also, the provenance of information in reports is important, the Crown should be prepared to account for where information comes from beyond saying: "it's written in the report."

Overview

[2] The applicant, E.B., is charged with several serious offences and was detained following a bail hearing. He has applied to have his detention reviewed pursuant to ss. 520 and 525 of the Criminal Code. E.B. is by any measure a person to whom s. 493.2 applies. He is of Aboriginal descent, black, mentally ill, poor and suffers from addiction. At the same time, he is charged with serious offences and has a very lengthy criminal record that includes numerous convictions for offences of violence and for disobeying court orders. How s. 493.2 should be applied and what effect it has on the court’s ultimate determination is a central issue on this application.

The Charges

[4] The applicant is charged with break and enter, sexual assault, choking, mischief, breach of recognizance, assault with a weapon, breaking out of a place and possession of a weapon. The offences are alleged to have been committed in February 2020. Because there is a publication ban, I will not outline the allegations in detail. The applicant allegedly became involved in an altercation with two individuals, one of whom he has known for 10 years, while in their apartment and threatened them with a kitchen knife. He allegedly then left the apartment by breaking into another apartment through the balcony and while there choked the resident and touched her breasts. He then left that apartment and damaged the door while doing so. There is no indication of anyone suffering injuries.

[5] The applicant is also facing charges of aggravated assault and obstruct peace officer from May 2020 arising out of an altercation at the Toronto South Detention Centre (“TSDC”). He has not had a bail hearing on those charges and they are not before this court....

[6] At the time of the alleged offence, the applicant was the subject of a recognizance to keep the peace issued pursuant to s. 810.2 of the Criminal Code. He had been reporting to the police once per month as required by the recognizance since October 2019.

The Accused

[7] The applicant is 42 years old. He is black. He is also of Mi’kmaq descent on his father’s side but had little connection with his indigenous heritage until he served time in a federal penitentiary. While there, he attended sweat lodges and counselling sessions with Elders and also completed the Aboriginal Multi-Target High Intensity Program.

[8] The applicant’s father was frequently in prison for drug trafficking when the applicant was growing up and died during an altercation in prison when the applicant was 13 years old. The applicant’s mother abused alcohol while the applicant was growing up and he apparently suffered verbal and physical abuse at her hands while young, although it appears that they have a better relationship now and she is willing to act as his surety. The family lived in poverty in an area of Toronto which the applicant’s uncle and proposed surety described in his testimony as a “ghetto.” The applicant was in and out of foster care between the ages of nine and 16.

[9] The applicant has been diagnosed with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (“PTSD”) which resulted from being assaulted while in custody. He is prescribed medication for this condition.

His Record

[11] The applicant has a very lengthy criminal record which begins in 1991 while he was a youth. Between 1991 and 2005, he accrued 43 convictions, most of which were for drug offences and failing to comply with court orders resulting in sentences ranging from a few days to a few months in length. However, there was a conviction for robbery in 1997 for which he received a 12-month sentence. In 2005, the applicant received a 12-month conditional sentence for trafficking in a Schedule I substance. That sentence was converted to a custodial sentence four months later when the applicant was again convicted for trafficking and possessing the proceeds of crime. This time, he received a sentence of 452 days consecutive to the sentence being served, for a total of two years. This was his first penitentiary sentence.

[12] The applicant’s record became much more violent following the penitentiary sentence, which he served most of because he repeatedly violated conditions of his statutory release. He was convicted of aggravated assault in 2007 for which he received 18 months and assault causing bodily harm in 2009 for which he received two years. He also continued to accumulate convictions for drug offences and failing to comply with court orders. In 2013, he was convicted of aggravated assault and assault causing bodily harm after stabbing one man in the neck and breaking the jaw of another. His most recent conviction is from April 2018 for uttering threats to a former intimate partner. The applicant was denied parole and remained in the penitentiary until October 2019. At the time of his release, he was ordered to enter into a recognizance pursuant to s. 810.2 of the Criminal Code for a period of two years.

His Custodial Risk-Assessment

[13] ... The Violence Risk Appraisal Guide (“VRAG”) apparently indicated that the applicant has a 44% probability of violently re-offending within seven years and a 58% probability of doing so within 10 years. ...

Error in Relying on Unsourced Information in Bail

[18] The alleged error of law is based on the Justice of the Peace’s finding respecting the applicant’s mother’s credibility. During the mother’s testimony at the bail hearing, she was asked about an incident in 2002 which led to the applicant being convicted of assaulting her. She testified that this assault consisted of the applicant throwing an orange at her. Her evidence in this regard was not challenged in cross-examination. During submissions, Crown counsel referred the Justice of the Peace to a CSC document which mentioned a Toronto Police “Supplementary Report” respecting the 2002 assault. The description of the assault in that report was far more serious than the orange-throwing incident described by the applicant’s mother. Based on this, the Justice of the Peace concluded that the applicant’s mother “did not tell the truth” and was not credible. This in turn led her to reject the proposed release plan as unsuitable.

[19] With respect, the Justice of the Peace erred in relying on the information in the CSC document. There was no indication in the material as to the source of the information. During submissions before me, Crown counsel was unable to provide me with the source of the information in the Supplementary Report other than to say that it came from “the police file”, which she submitted meant that it was credible and trustworthy. I do not agree. In all likelihood, the information came from a police synopsis prepared at the time of the applicant’s arrest and may have been completely different than the facts acknowledged by the applicant when he pled guilty to the offence. 1 At the very least, the discrepancy should have been put to the applicant’s mother so that she could have an opportunity to explain: R. v. Quansah, 2015 ONCA 237, 125 O.R. (3d) 81, at paras. 76-79. While it was open to the Justice of the Peace to reject the mother’s testimony, it was not open to her to do so on the basis that her recollection of events that took place 18 years ago differed from the description in a document of unknown provenance which the witness had no opportunity to explain.

[20] Given that there is a material change in circumstance in the form of a new surety who was not available at the initial bail hearing, a de novo consideration of the applicant’s bail is appropriate regardless of any error....

Section 493.2 of the Criminal Code

[21] Section 493.2 was recently added to the Criminal Code together with a number of other amendments. 2 The full text of the section is as follows:

493.2 In making a decision under this Part, a peace officer, justice or judge shall give particular attention to the circumstances of

(a) Aboriginal accused; and

(b) accused who belong to a vulnerable population that is overrepresented in the criminal justice system and that is disadvantaged in obtaining release under this Part.

Section 493.2 was enacted at the same time as s. 493.1, which provides as follows:

493.1 In making a decision under this Part, a peace officer, justice or judge shall give primary consideration to the release of the accused at the earliest reasonable opportunity and on the least onerous conditions that are appropriate in the circumstances, including conditions that are reasonably practicable for the accused to comply with, while taking into account the grounds referred to in subsection 498(1.1) or 515(10), as the case may be.

[22] Like all new enactments, the amendments are presumed to be remedial by virtue of s. 12 of the Interpretation Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. I-21: R. v. Gladue, 1999 CanLII 679 (SCC), [1999] 1 S.C.R. 688, at paras. 25-26; Bell ExpressVu Limited Partnership v. Rex, 2002 SCC 42, [2002] 2 S.C.R. 559, at para. 26. Their clear purpose is to remedy the problem of overuse of pre-trial custody as well as the overrepresentation of certain populations in the criminal justice system in general and the remand population in particular.

Section 493.1

[23] Section 493.1 codifies the principles enunciated in R. v. Antic, 2017 SCC 27, [2017] 1 S.C.R. 509, which affirmed the importance of the “ladder principle” that the least onerous conditions must be imposed on an accused at a bail hearing unless the Crown can justify why more onerous conditions are necessary. The Court in Antic was clearly concerned about the growing increase in the remand population in Canada...

[25] Section 493.2 also clearly addresses a problem in need of remediation. As noted in Myers, Indigenous individuals account for approximately one quarter of the adult remand population. The Court made a similar observation earlier in R. v. Summers, 2014 SCC 26, [2014] 1 S.C.R. 575, at para. 67, where it cited statistics showing that “Aboriginal people are more likely to be denied bail, and make up a disproportionate share of the population in remand custody.”

[26] Indigenous people are not the only historically disadvantaged group to be over-represented in the criminal justice system. Racialized individuals, particularly those who are black, are also over-represented: R. v. Golden, 2001 SCC 83, [2001] 3 S.C.R. 679, at para. 83; R. v. Jackson, 2018 ONSC 2527, 46 C.R. (7th) 167, at paras. 40-48; R. v. Elvira, 2018 ONSC 7008, at para. 22; R. v. K.H., 2019 ONCJ 525, at paras. 59-60; R. v. Dykeman, 2019 NSSC 361, at para. 11. The same is true of those who suffer from mental illness: R. v. Ejigu, 2016 BCSC 1487, 340 C.C.C. (3d) 53, at para. 300; Hon. R. Schneider, “The Mentally Ill: How They Became Enmeshed in the Criminal Justice System and How We Might Get Them Out,” (2015), Department of Justice Canada Provocative Paper Series, at p. 3.

[27] The reasons why certain populations are overrepresented in the criminal justice system are complex. However, in my view it is beyond dispute that systemic racism in the justice system is part of the cause. Where the overrepresentation relates not to those who have been convicted of crimes, but those who are presumed innocent, the problem is all the more dire. This is a problem that must be remedied. Section 493.2 is clearly intended to be part of that remedy.

Preserving the Presumption of Innocence

[38] ... One way in which systemic factors may be considered in the context of an accused’s antecedents at a bail hearing was explained in “Gladue and Bail: The Pre-trial Sentencing of Aboriginal People in Canada” at p. 355:

Courts must consider the potential for institutional bias in the arrest and charging of the accused, including the possibility of over-policing and over-charging. Both the charges against the accused as well as any prior criminal antecedents should be viewed with the current and historical context of the over-zealous policing of Aboriginal people in mind;. . . .

To the extent that the accused’s criminal antecedents are attributable to systemic factors deriving from colonialism, such as poverty or substance abuse, courts should view prior convictions as systemically motivated rather than as intentional disregard for the law, particularly in relation to conviction for failing to attend court or failing to comply with conditions. Any allegations of failing to attend court should be scrutinized to determine whether there was an intention to abscond or evade the law or whether systemic factors prevented the accused from appearing in court; ….

Other Vulnerable Groups

[40] The discussion thus far as been about Aboriginal accused and relates to s. 493.2(a). This is because there is a significant body of jurisprudence on how the unique circumstances of Aboriginal people should be considered at a sentencing hearing. There are fewer cases dealing with members of other vulnerable and disadvantaged populations that are over-represented in the criminal justice system, although there are some: Jackson; R. v. Morris, 2018 ONSC 5186, 422 C.R.R. (2d) 154; R. v. Kandhai,2020 ONSC 3580, at paras. 60-77; R. v. Husbands, 2019 ONSC 6824, at paras. 75-83. In my view, the approach taken to s. 493.2(b) should be similar to the one taken to s. 493.2(a). The accused’s history and antecedents must be considered in light of systemic issues to ensure that the accused is not unfairly disadvantaged in obtaining bail.

How does 493.2 Apply to 515(10)?

[43] Where s. 493.2 comes into play, in my view, is in the court’s examination of the type of factors that are relied upon to make the determination of whether detention is necessary. For the secondary ground, which is at issue in this case, this usually consists of the accused’s criminal antecedents as well as the nature of the allegations. Making an accurate determination of whether those factors lead to the conclusion that detention is necessary requires that they be considered having regard to the unique circumstances of the accused, including any relevant systemic factors. This was the approach taken in R. v. Chocolate, 2015 NWTSC 28, at paras. 49-50:

In my view, honouring the constitutional right to reasonable bail requires consideration of the socio-economic factors present in the life of any accused, regardless of whether they are Aboriginal. For many Aboriginal people who come before the courts, however, the factors identified in Gladue will form a large part of their overall socio-economic context. It would be unreasonable and unfair to conclude detention is justified based solely on an accused’s criminal record and/or the circumstances of the alleged offence without considering the role Gladue factors may have played in leading to that person committing criminal acts in the past, being charged again and, consequently, seeking bail. There simply must be more than a superficial review of an accused's past criminal conduct and/or the circumstances leading to the current charge.

An examination of the intergenerational impact of the residential school system, cultural isolation, substance abuse, family dysfunction, poverty, inadequate housing, low education levels and un- or underemployment on an Aboriginal offender may inform questions about why an accused has an extensive criminal record and, if applicable, why that person has demonstrated an inability to comply with pre-trial release conditions in the past. They will also inform the decision about whether, given the accused's circumstances, there are release conditions which can be imposed so that future compliance is realistic and concerns about securing attendance at trial, public safety and overall public confidence in the justice system are meaningfully addressed.

See also Magill, at para. 26; R. v. Gibbs, 2019 BCPC 335, at para. 23; R. v. Silversmith (2008), 77 M.V.R. (5th) 54 (Ont. S.C.J.), at paras. 23-25. These types of factors are relevant not only to an accused’s antecedents, but also to his alleged involvement in the index offence: R. v. C.W., 208 ONSC 4783, at para. 46.

Application to the Case

The Applicant's Record - Breaches

[46] Breaches of court orders are not all created equal. They can consist of being out of one’s home a few minutes after a curfew, missing an appointment with a probation officer, or possessing drugs when prohibited from doing so. These have been referred to as “system-generated offences”: R. v. N.H., 2020 ONCJ 295, at paras. 14-20; T. Quigley, “Has the Role of Judges in Sentencing Changed … Or Should It?” (2000), 5 Can. Crim. L. Rev. 317. At the other end of the spectrum, a breach can result from the commission of a serious criminal offence.

[47] I have not been provided with the particulars of any of the applicant’s convictions for failing to comply with probation orders or recognizances. Some of them occurred on the same dates as convictions for other offences, which suggests that the breach may have consisted of the commission of the other offences. However, it may also be that the applicant decided to resolve a number of outstanding charges at the same time.

[48] In my view, s. 493.2 requires me to consider the applicant’s membership in vulnerable and overrepresented populations when determining what weight to assign to his criminal record for failing to abide by court orders. In doing so, there are certain facts about which I take judicial notice. The first is that as was recently recognized in R. v. Zora, 2020 SCC 14, at para. 26, there are “widespread problems … with the ongoing imposition of bail conditions which are unnecessary, unreasonable, unduly restrictive, too numerous, or which effectively set up the accused to fail.” The effect of imposing such conditions was described in Zora at para. 57:

… [B]reach charges often accumulate quickly…. People with addictions, disabilities, or insecure housing may have criminal records with breach convictions in the double digits. Convictions for failure to comply offences can therefore lead to a vicious cycle where increasingly numerous and onerous conditions of bail are imposed upon conviction, which will be harder to comply with, leading to the accused accumulating more breach charges, and ever more restrictive conditions of bail or, eventually, pre-trial detention (C.M. Webster, “Broken Bail” in Canada: How We Might Go About Fixing It (June 2015), at p. 8 (“Webster Report”); Canadian Civil Liberties Association and Education Trust, Set Up to Fail: Bail and the Revolving Door of Pre-trial Detention, by A. Deshman and N. Myers (2014) (online), at pp. 49 and 66 (“CCLA Report”); M.E. Sylvestre, N. K. Blomley and C. Bellot, Red Zones: Criminal Law and the Territorial Governance of Marginalized People [Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019], at p. 132; Pivot Legal Society, Project Inclusion: Confronting Anti-Homelessness & Anti-Substance User Stigma in British Columbia, by D. Bennett and D.J. Larkin (2019) (online), at p. 101 (“Pivot Report”)).

[49] The accumulation of breach convictions also has another potential effect. As noted in Zora, accumulated breach convictions will eventually lead to detention before trial. This in turn leads to an incentive to plead guilty, regardless of whether one actually is guilty. This is especially true with respect to more minor offences that result in sentences of imprisonment for a few months, for it is those where the accused risks spending more time in pre-trial custody than he would otherwise serve unless he pleads guilty: Antic, at para. 66; Myers, at para. 51; C. Leclerc and E. Euvrard, “Pleading Guilty: A Voluntary or Coerced Decision?” (2019), 34 Can. J. L. & Soc’y 457. These types of short sentences make up the bulk of the first 14 years of the applicant’s record before he served his first penitentiary sentence.

[50] I should not be taken as having concluded that all of the applicant’s breach convictions related to unnecessary or unreasonable bail conditions. However, in my view, a proper contextual consideration of his record means that I should exercise caution before relying on his numerous breach convictions to conclude that he is incapable of abiding by bail conditions.

The Applicant's Record - Drugs

[51] As noted, the applicant has a history of addiction. Sixteen of his convictions are for possessing or selling drugs, and many of his breach convictions occur on the same day as drug offence convictions. Repeated drug offences by an addict are consistent with an inability to overcome addiction and should not be viewed as “an affront to the court”: R. v. J.H. (1999), 1999 CanLII 3710 (ON CA), 135 C.C.C. (3d) 338 (Ont. C.A.), at para. 23. This is especially true with respect to convictions for possession, as opposed to trafficking.

The Applicant's Record - Over-policing

[52] In R. v. Le, 2019 SCC 34, at paras. 89-97, based on a number of authoritative studies, a majority of the Supreme Court of Canada found that there is “disproportionate policing of racialized and low-income communities” in Canada.

[53] In my view, the fact that individuals such as the applicant are over-policed must be taken into account when assessing the weight to be given to this criminal record: R. v. King, 2019 ONSC 6851, at paras. 35-46.

The Applicant's Record - Conclusion

[59] The foregoing discussion should not be taken to mean that the applicant’s antecedents are not a cause of significant concern. They clearly are, even when subjected to the type of contextual examination I believe s. 493.2 requires. There is no question that the applicant has a long history of failing to abide by court orders and that he had repeatedly engaged in criminal conduct, including serious crimes of violence. However, giving particular attention to the applicant’s circumstances as an Indigenous accused and one who belongs to a vulnerable and overrepresented population means that I should not simply write him off as “just a recidivist”, as he was referred to by one of the judges who sentenced him in a decision provided to me by counsel.

Secondary Ground Concerns

[60] Section 515(10)(b) of the Code states that detention is justified on the secondary ground where it is necessary for the protection or safety of the public “having regard to all the circumstances including any substantial likelihood that the accused will, if released from custody, commit a criminal offence or interfere with the administration of justice.” In this context, a “substantial likelihood” means “a probability of certain conduct, not a mere possibility. And the probability must be substantial, in other words, significantly likely”: R. v. Manasseri, 2017 ONCA 226, at para. 87.

[61] The consideration of the applicant’s circumstances mandated by s. 493.2 obviously does not lead to the conclusion that secondary ground concerns can be discounted in this case. There are clearly significant secondary ground concerns. However, as was observed in R. v. Tully, 2020 ONSC 2762, at para. 23, “the relevant question is not whether secondary ground concerns exist, but whether they can be adequately addressed by the proposed release plan, having regard to all of the relevant factors.” Those relevant factors include the circumstances which s. 493.2 requires the court to consider.

[62] ... The applicant’s uncle has never acted as a surety for him before. I am satisfied that he would supervise him closely and would not hesitate to contact the authorities in the event of a breach.

[64] Under the terms of the proposed plan, the applicant would remain in his residence at all times unless attending work, scheduled court appearances or scheduled appointments with a physician, dentist, lawyer or counsellor. When outside his residence for one of these purposes, he would be required to be in the company of a surety. The plan would be supplemented be electronic monitoring, which would provide some independent assurance that the applicant is either at home or with a surety.

[65] The proposed plan is by no means foolproof. Nor is it required to be. However, it does prevent the applicant from attending certain parts of the city which have proved problematic for him and also minimizes the prospect of him finding himself in the types of situations where he has in the past resorted to violence. Having carefully considered the applicant’s antecedents, the allegations, and the details of the proposed plan, I am satisfied that there is not a substantial likelihood that the applicant will commit further offences if released.

Tertiary Ground

[66] The Crown also relies on the tertiary ground in s. 515(10)(c) of the Code, which justifies detention where it is necessary to “maintain confidence in the administration of justice, having regard to all the circumstances.” The Justice of the Peace at the initial bail hearing was not satisfied that detention was required on the tertiary ground. Nor am I. While the alleged offences are serious, the strength of the Crown’s case is unclear and there is no allegation of the use of a firearm.

[67] The tertiary ground requires the court to consider the perception of reasonable members of the community who are informed about the philosophy behind the bail provisions in the Code, Charter values and the actual circumstances of the case: R. v. St.-Cloud, 2015 SCC 27, [2015] 2 S.C.R. 328, at paras. 75-80. This would include the type of circumstances referred to in s. 493.2 of the Code.

Conclusion

[69] For the foregoing reasons, the application is granted and the applicant is admitted to bail on the terms and conditions described earlier, as set out in the Order issued on July 8, 2020.