This week’s top three summaries: R v Anderson, 2019 SKCA 27, Canadian Civil Liberties Association v Canada (Attorney General), 2019 ONCA 243, and R v Wang, 2019 BCPC 52.

R. v. Anderson (SKCA)

[Mar 22/19] Procedure - Remedies for Unsolicited Inadmissible Evidence - Prior Sexual Assault Case of Accused - 2019 SKCA 27 [Reasons by Ryan-Froslie J.A., with Jackson J.A., and Schwann J.A. Concurring]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Witnesses say the darnedest things sometimes. Whether well-meaning or ill-intentioned, their utterances can sometimes be legally inadmissible as against an Accused. Here, the witness volunteered that the accused had a prior sexual assault case. This is obviously inadmissible bad character evidence, but what is interesting about this decision is the discussion of what a court and counsel should do in this situation to fix it. The two options appear to be an immediate direction to the jury to disregard the evidence and a mistrial declaration. One may dispute whether a direction to a jury can ever achieve a jury actually ignoring something they have heard, but this appears to be an accepted fix. This decision provides some guidelines that counsel can use to achieve a fair trial or a new one when unexpected evidence of this sort arises.

Pertinent Facts

The accused had anal sex with the complainant but defended on the basis of consent or honest but mistaken belief in consent. (Para 3)

"The alleged sexual assault occurred after a night of drinking and partying at Mr. Anderson's home. The complainant was described by witnesses as being "flirty and touchy" and during the evening had sat on Mr. Anderson's knee in the hot tub." (Para 4)

"Around 12:00 a.m., the complainant was so intoxicated he started to sink face-first into the hot tub. One of the other guests pulled the complainant out of the hot tub and Mr. Anderson put him on a bed in a room located on the main floor of the house. A couple of hours later, when Mr. Anderson and another guest, Mr. Caplette, went upstairs to retire, they found the complainant in the upstairs guest bedroom. Mr. Caplette went downstairs to sleep and Mr. Anderson crawled into bed with the complainant." (Para 5)

"Around 3:30 a.m., the complainant testified he woke up to find Mr. Anderson having anal intercourse with him. When he asked Mr. Anderson to stop, he did so. The complainant testified he had no memory of anything that had occurred from the time he was in the hot tub until he awoke." (Para 6)

"Mr. Anderson testified the complainant had initiated sexual relations with him and that he believed, given the complainant's actions, that he was consenting to sexual intercourse." (Para 7)

"The circumstances underpinning Mr. Anderson's argument are that during the examination-in-chief of Mr. McNally, a Crown witness, Mr. McNally gratuitously stated that Mr. Anderson had been involved in another sexual assault. The relevant exchange was as follows:

Q How did you end up making an offer to [the complainant]? How did that happen? What — what happened there?

A Skipp wanted an offer to be made because it would be cheaper than paying his lawyer for a second sexual assault case." (Para 10)

"Defence counsel immediately objected and the jury was excused. Defence counsel contended the evidence was prejudicial and inadmissible and that the damage was probably "irreparable". He indicated the following: "at the very least, the jury needs to be given a strong warning that that particular comment needs to be stricken from — as much as it can be, hopefully it can be, from their — their collective minds and Mr. McNally needs to be admonished that he is not to go there again unless I bring it up myself"." (Para 11)

Instead of an immediate direction to the jury defence and Crown agreed this should happen in the charge to the jury (Para 12)

"In his charge, the trial judge directed the jury as follows:

Before I start to deal with some of the evidence that you should consider I want to comment on two statements made by witnesses that are not to be considered by you. The first relates to a statement made by [Mr.] McNally, in — it contained — and it was contained in the cross-examination by Mr. Mitchell involving the allegation that Mr. McNally offered money to [the complainant] at the request of Mr. Anderson to drop the charge. Mr. McNally made a comment that Mr. Anderson had done this in the past. That comment was without foundation. There is no evidence before you that any such situation occurred. You are to ignore that comment made by Mr. McNally and it shall form no part of your deliberations. (Emphasis added)" (Para 13)

Solutions to the Problem of Inadmissible Evidence Heard by a Jury

"Generally, when inadmissible evidence is presented before a jury, whether intentionally or inadvertently (as in this case), a trial judge should either immediately caution the jury to disregard the evidence or, if the trial judge believes such a caution would not be sufficient, he or she should order a mistrial: R. v. D. (L.E.), [1989] 2 S.C.R. 111 (S.C.C.) at 124-125 [D.(L.E.) ]." (Para 20)

"Justice Sopinka, writing for the majority in D.(L.E.) , stated the following (at 126-127):

...I agree with the following statement of the Appeal Division, at pp. 91-92, with respect to the duty of a trial judge:

In a criminal trial there is a duty on the trial Judge to exclude inadmissible evidence even though adduced by counsel for the accused or not objected to, and should inadmissible evidence be adduced, the trial Judge should either instruct the jury immediately to disregard it or, if it is of so prejudicial a nature that the jury would not have the capability of disregarding it, he should discharge the jury and order a new trial: [citations omitted].

If the trial judge was of the view that an immediate caution to the jury to disregard the evidence was insufficient to ensure a fair trial, then his course was to direct a mistrial rather than admit the evidence of similar acts which had previously been excluded." (Para 24)

"Justice Sopinka discussed the prejudicial effect of such evidence, which informs the basis for excluding it, namely (a) that the jury may assume the accused is a "bad person" who is likely guilty of the offence charged, (b) that there might be a tendency to punish the accused for past conduct, and (c) that the jury might focus on whether the accused actually committed the similar acts and substitute them for the offences actually charged (D.(L.E.) at 127-128)." (Para 25)

Here "the trial judge should either have given an immediate caution to the jury to disregard that evidence or, if he believed such a caution would not be sufficient, he should have ordered a mistrial. The trial judge was led to do neither by defence counsel, who agreed with Crown counsel's suggestion that, instead of an immediate caution, the trial judge should address the matter in his charge to the jury. Defence counsel asserted a clear instruction to disregard the evidence would be required. There was no obvious tactical reason for defence counsel agreeing to this course and thus, in my view, it did not overcome the trial judge's duty as described at page 127 of D.(L.E.)." (Para 26)

"Assuming it was possible to give the direction in the final charge, in my view, the trial judge's instruction did not adequately identify the evidence to be disregarded and, as such, there was an error in law." The trial judge focused the jury on disregarding the direction to offer money to the complainant instead of the second sexual assault. There was nothing in the caution to link it to the inadmissible evidence. (Paras 27-28)

Neither the failure of defence counsel to object nor the curative proviso saved this case for the Crown. (Paras 31, 37)

Canadian Civil Liberties Association v. Canada (Attorney General) (ONCA)

[Mar 28/19] Section 12 - Cruel and Unusual Punishment - Administrative Segregation over 15 days Struck Down 2019 ONCA 243 [Reasons by Benotto J.A., Strathy C.J.O., and Roberts J.A. Concurring]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: The ONCA struck down provisions of the federal legislation allowing prolonged segregation of prisoners. It defined prolonged as anything over 15 consecutive days. The decision found this to be cruel and unusual treatment. The decision can be used by defence counsel to argue for enhanced credit for pre-trial detention where segregation has exceeded 15 consecutive days. The extensive acceptance and reproduction of expert evidence of the effects of prolonged segregation is very persuasive and will have an affect on trial and sentencing courts.

Overview

"The distinguishing feature of solitary confinement is the elimination of meaningful social interaction or stimulus. It has the potential to cause serious harm which could be permanent. Federal legislation permits its use in penitentiaries across Canada. It is called "administrative segregation" and is permitted to maintain safety and security or to conduct investigations. The appellant, the Canadian Civil Liberties Association ("CCLA"), submits that ss. 31-37 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act, S.C. 1992, c. 20 (the "Act"), the legislative provisions authorizing administrative segregation, are unconstitutional." (Para 1)

"[P]rolonged administrative segregation of any inmate, which is segregation for more than 15 consecutive days, does not survive constitutional scrutiny under s. 12." (Para 4)

"I reach this conclusion because prolonged administrative segregation causes foreseeable and expected harm which may be permanent and which cannot be detected through monitoring until it has already occurred. Legislative safeguards are inadequate to avoid the risk of harm. In my view, this outrages standards of decency and amounts to cruel and unusual treatment. I conclude that the provisions in the Act authorizing prolonged administrative segregation infringe s. 12 and the infringement cannot be justified under s. 1. It follows that a remedy under s. 52(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982 is appropriate." (Para 5)

Pertinent Facts

"An inmate who is held in administrative segregation is permitted out of his or her cell for a minimum of two hours per day plus time for a daily shower." (Para 7)

"The discretion to order administrative segregation rests with the institutional head, usually the prison warden or his or her delegate. Once that discretion is exercised, the inmate is placed in a segregated prison cell and remains there indefinitely until the institutional head decides to order release. The inmate is to be allowed out of his or her cell for a minimum of two hours daily, including one hour for exercise outdoors, and must also be given an opportunity to take a daily shower. At all other times the inmate remains locked in his or her cell, except if there is a lockdown when they do not leave their cells at all." (Para 19)

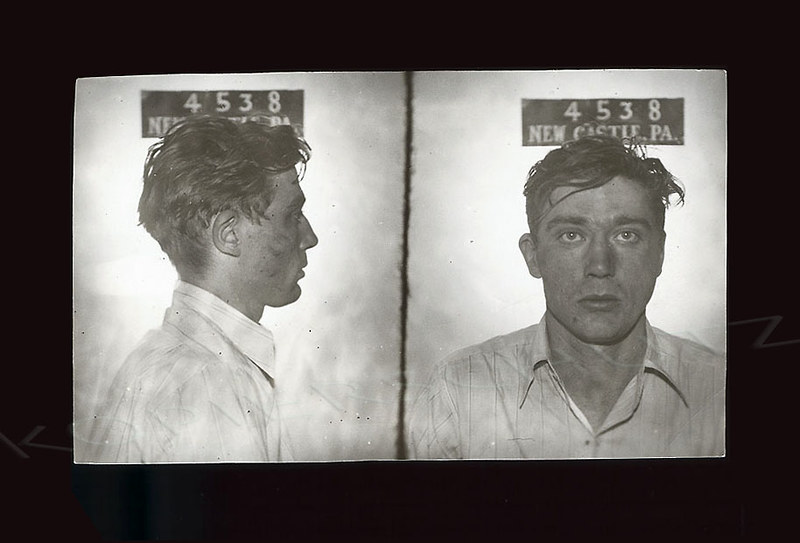

"As I have noted, the distinguishing feature of administrative segregation is the elimination of meaningful social interaction or stimulus. The photographic evidence adduced by the CCLA in this case depicts a small cell where the inmate is held. It contains a narrow platform with a thin mattress overtop, a toilet, a sink, maybe or maybe not a small table, maybe or maybe not a small window. The heavy steel door has a small food slot a few feet off the ground. It is often through this food slot that interactions with staff and health personnel take place." (Para 20)

"The United Nations has recently adopted rules governing the treatment of prisoners: the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (the Nelson Mandela Rules), UNGAOR, 70th Sess, UN Doc A/Res/70/175 (17 December 2015) (the "Mandela Rules"). The Mandela Rules are an authoritative interpretation of international rules including the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, 10 December 1984, UNTS 1465 (entered into force 26 June 1987, ratified by Canada 24 June 1987). The Mandela Rules define solitary confinement as confinement of a prisoner "for 22 hours or more a day without meaningful human contact." They prohibit the use of prolonged solitary confinement, which is confinement for a period in excess of 15 days, and provide that solitary confinement should "be used only in exceptional cases as a last resort, for as short a time as possible and subject to independent review"." (Para 23)

"Professor Méndez explained that the essence of solitary confinement is a lack of meaningful social contact with the result that social stimulus is insufficient to allow the individual to remain in a reasonable state of mental health. When individuals are deprived of social stimulation, they become incapable of maintaining an adequate state of alertness and attention to their environment. If this occurs for even a few days, brain activity shifts toward an abnormal pattern." (Para 27)

"Bill C-83, An Act to amend the Corrections and Conditional Release Act and another Act, amends ss. 31-37 of the Act. It was introduced in the House of Commons on October 16, 2018 and passed third reading on March 18, 2019. It is currently before the Senate." (Para 43)

"Under the proposed new system, those in structured intervention units will be given the opportunity to spend a minimum of four hours a day outside their cell, including a minimum of two hours a day interacting with others. The Bill does not place a cap on the number of consecutive days an inmate may spend in a structured intervention unit. Instead, it mandates that there be ongoing monitoring of the health of those in structured intervention units." (Para 45)

"Dr. Hannah-Moffat spoke of the negative effects of administrative segregation. In particular, she described the following effects of administrative segregation, both short-term and prolonged, as established in the literature: [some reproduced]

- long-term segregation may lead to the development of previously undetected psychiatric symptoms;

- segregation appears to be a significant risk factor for the development of psychiatric symptoms including depression and suicidal ideation;

- segregation has repeatedly been linked to appetite and sleep problems, anxiety, panic, rage, loss of control, depersonalization, paranoia, hallucinations, self-mutilation, increased rates of suicide and self-harm, an increased level of violence against others, and higher rates of frustration;

- segregation may lead to cognitive-behavioral problems among prisoners: difficulty solving interpersonal problems, unawareness of the consequences of their actions, inability to make positive choices, and a tendency to display disregard for others as a result of being socially unaware and impulsive;" (Para 76)

"Based on the evidence he accepted, the application judge found that "prolonged administrative segregation poses a serious risk of negative psychological effects": at para. 248. These negative effects are "foreseeable and expected", "may not be observable", result from "abnormal psychological stress and will if the stay continues indefinitely result in permanent psychological harm": at paras. 240, 241, 252." (Para 77)

Section 12 Analysis

"Recently in R. v. Boudreault, 2018 SCC 58 (CanLII), 369 C.C.C. (3d) 358, the court when considering the mandatory victim surcharge scheme in the context of s. 12 said at para. 94:

…the impact and effect of the surcharge, taken together, create circumstances that are grossly disproportionate, outrage the standards of decency, and are both abhorrent and intolerable. Put differently, they are cruel and unusual and, therefore, violate s. 12." (Para 59)

"The practical effect of monitoring combined with a proper application of s. 87(a) is that it allows the CSC to remove an inmate from administrative segregation only after they have detected decompensation which has already occurred. In other words, monitoring, while effective at identifying inmates who have suffered harm, is ineffective at preventing it." (Para 79)

"In conclusion, the application judge's error in relying on the effectiveness of monitoring undermines his conclusion that ss. 31-37 do not breach s. 12 insofar as they permit prolonged segregation." (Para 81)

"Section 12, which prohibits cruel and unusual treatment and punishment, involves a comparative approach. In my view, the application judge also erred in his s. 12 analysis in applying the wrong comparative approach." (Para 82)

" In any event, the test to establish a violation of s. 12 is the same whether the court considers administrative segregation "punishment” or "treatment": R. v. Olson (1987), 1987 CanLII 4314 (ON CA), 62 O.R. (2d) 321 (C.A.), at p. 336, aff’d, 1989 CanLII 120 (SCC), [1989] 1 S.C.R. 296; Ogiamien, at para. 7. In either case, the punishment or treatment must be “so excessive as to outrage standards of decency” or “grossly disproportionate to what would have been appropriate”. The analysis is an inherently comparative exercise, measuring the punishment or treatment experienced against the punishment or treatment that is appropriate in the circumstances." (Para 86)

"In Ogiamien, at para. 10, Laskin J.A. said that there is a two-step process to determine whether treatment is cruel and unusual:

The first step establishes a benchmark. In this case step one looks at the treatment of [the inmate] under "appropriate" prison conditions — that is their treatment under ordinary conditions in the remand units when there were no lockdowns. Step two assesses the extent of the departure from the benchmark. In this case step two looks at the effect of the lockdowns on [the inmate]'s treatment. If the effect of the lockdowns resulted in treatment that was grossly disproportionate to their treatment under ordinary conditions then their s.12 rights would be violated." (Para 90)

"In my view, a proper comparative exercise must consider the effects of prolonged administrative segregation against incarceration in an ordinary prison range. This is precisely what the expert evidence adduced in this case addresses. Compared to the treatment of inmates in general population, the evidence reveals that inmates held in prolonged administrative segregation are at risk of severe and often enduring negative health consequences." (Para 97)

"This evidence led the application judge to conclude that, where administrative segregation exceeds 15 consecutive days, inmates face "foreseeable and expected" harm. As he stated at para. 254, "there is no serious question the practice of keeping an inmate in administrative segregation for a prolonged period is harmful and offside responsible medical opinion." Inmates under normal prison conditions are not exposed to harm of this sort." (Para 98)

"The effect of prolonged administrative segregation is thus grossly disproportionate treatment because it exposes inmates to a risk of serious and potentially permanent psychological harm." (Para 99)

"Under s. 87(a), the institutional head need only "consider" the inmate's health in deciding whether to place an inmate in, or remove an inmate from, administrative segregation. The word "consider" is significant. It implies that the inmate's health is merely one consideration among others. It is not the paramount consideration. By structuring the institutional head's discretion in this way, s. 87(a) authorizes prioritizing other considerations over the inmate's health, so long as the inmate's health forms part of the decision-making process. Thus, even when properly applied, s. 87(a) does not protect against the risk of an inmate suffering cruel and unusual treatment." (Para 105)

The legislation cannot be saved by any presumption that CSC will exercise their discretion to avoid an unconstitutional result: R. v. Nur, 2015 SCC 15 (CanLII), [2015] 1 S.C.R. 773, and R. v. Appulonappa, 2015 SCC 59 (CanLII), [2015] 3 S.C.R. 754 (Para 106-110)

"Even when conscientiously applied by the institutional head, ss. 31(2), 31(3) and 69 do not preclude the possibility of prolonged administrative segregation. I conclude that the legislative safeguards are inadequate to render the Act constitutional." (Para 115)

"Prolonged administrative segregation subjects inmates to grossly disproportionate treatment. As I have explained, ss. 31-37 of the Act authorize and do not safeguard against such treatment. Thus, the Act infringes s. 12." (Para 119)

The legislation was not saved by s.1 of the Charter (Para 126)

The legislation was immediately struck down to the extent it authorised "prolonged administrative segregation." [as defined above] (Para 130)

R v Wang (BCPC)

[Mar 27/19] – Self Defence – 2019 BCPC 52 [R. Harris Prov. J.]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: This case provides an excellent example of self-defence working even in a situation of serious charges and real physical damage to the aggressor. The accused struck the assailant with a pot of boiling water.

Pertinent Facts

“Mr. Wang and the complainant, Mr. Yang, peacefully coexisted as roommates for almost one year. This ended on March 13, 2018, when an altercation culminated in Mr. Wang throwing boiling water on Mr. Yang. Mr. Yang suffered serious burns and Mr. Wang was charged with aggravated assault and assault with a weapon; the boiling water." (Para 1)

"As such, I accept Mr. Yang became hostile and aggressive. I also accept that Mr. Yang pushed Mr. Wang knocking him backward and almost into the stove. I also accept Mr. Wang felt cornered and he grabbed the water when he believed that Mr. Yang was about to strike him. I accept that Mr. Wang's intention was to protect himself. Finally, I do not believe that Mr. Wang hit Mr. Yang with the pot or that he tried to punch him." (Para 45)

"Based on my findings, I conclude that Mr. Wang has met the "air of reality" burden as mandated in R. v. Cinous, [2002] 2.S.C.R. 3. I now turn to the issue of self-defence." (Para 46)

"Section 34 of the Criminal Code codifies self-defence and sets out factors and circumstances that a judge must consider. The section reads:

34 (1) A person is not guilty of an offence if:

(a) they believe on reasonable grounds that force is being used against them or another person or that a threat of force is being made against them or another person;

(b) the act that constitutes the offence is committed for the purpose of defending or protecting themselves or the other person from that use or threat of force; and

(c) the act committed is reasonable in the circumstances. (Para. 47)

"As for s. 34(1), if the Crown establishes that one of the three subsections do not apply then the defence is not available. This is because as per R. v. Randhawa, 2019 B.C.C.A. 15, all three of the criteria must be present for the defence to be available." (Para 48)

"Mr. Yang, a younger, stronger, and larger individual, pushed Mr. Wang on two occasions and Mr. Wang responded by pouring boiling water on Mr. Yang at the moment he felt that Mr. Yang was about to strike him. Mr. Wang poured the boiling water because he did not want to fight, nor, did he want to get hit." (Para 49)

"I now consider if the pouring of the boiling water was reasonable. As part of the circumstances, I observe Mr. Yang pushed Mr. Wang on two occasions. Ultimately, Mr. Wang, who was in a relatively confined area and up against the stove, believed that Mr. Yang was about to hit him." (Para 51)

"In my view, there were no other reasonable options for Mr. Wang. On the evidence, I find that the only item within easy reach was the pot of boiling water. I say "easy reach" because Mr. Wang was backed against the stove by Mr. Yang who was younger, stronger, and larger, he was also angry and had already assaulted Mr. Wong. The events unfolded very quickly; hence, the opportunity to search for another item was not viable. I recognize that there might have been an opportunity to flee, albeit with risk; however, the ability to retreat is only one factor and does not preclude reliance on s. 34 of the Code: R. v. Westhaver (1992), 119 N.S.R. (2d) at para. 8." (Para 52)

"Although Mr. Wang's use of the boiling water was a greater level of force than the pushes or the expected strike; an individual is not expected to measure the amount of force required to defend themselves with precision or to the degree of nicety. Clearly, the dynamics of the situation must permit some degree of reasonable flexibility: Brisson v. The Queen, [1982] 2 S.C.R. 227." (Para 53)

"As such, the Crown has failed to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Mr. Wang was not acting in self-defence." (Para 54)